Special people are needed to renovate a special place. The University of Virginia’s iconic Rotunda, designed by University founder Thomas Jefferson and later reenvisioned by famous American architect Stanford White, has been undergoing an extensive renovation and restoration that’s approaching its conclusion this fall.

Behind the project’s scaffolding and construction fencing, a number of highly trained and specialized artisans and craftspeople from the University and beyond have been hard at work on the many intricate details required for the renovation of a nearly 200-year-old building that, with the rest of the Academical Village, is on UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites. The range of these projects spans from careful work restoring a plaster eagle on the front portico to designing new student spaces to make sure the Rotunda remains at the heart of the University’s academic mission.

Meet a few of the many artisans and craftspeople behind the work and learn more about their specialized projects and the skills required to complete them.

Gianluca Ceccarelli

Gianluca Ceccarelli of Pedrini Sculpture Studio in Carrara, Italy, laser-scanned the remnants of the original Jeffersonian capitals, including the largest surviving piece, which has been kept on the patio of The Fralin Museum of Art, to generate 3-D images that were used to carve new capitals based on the designs of the original. The images were used to guide computer-controlled lathes to carve about 90 percent of each capital, with the rest completed by hand.

Below, Ceccarelli examines on his computer the laser scans of the original capital pieces. The Pedrini Studio replicated the original Jeffersonian capitals to replace White’s capitals, which had been made from softer domestic marble and were crumbling after years of exposure to the elements. After realizing the White capitals could not be repaired, University officials decided to return to Jefferson’s original Carrara marble. The 6,200-pound capitals were installed on the Rotunda using a custom-built framework that carried the marble blocks on a steel trolley.

Neil Dunbar

Neil Dunbar, who works for North American Construction Technologies of Milwaukee, was one of the many craftsmen working on the oculus — the circular skylight at the center of the Rotunda dome — which was installed with the help of a temporary support structure. Jefferson modeled the oculus in the Rotunda after the one in Rome’s Pantheon.

Dunbar, right, and Russ McClanahan of North American Construction Technologies complete the two-person job of installing the replacement oculus’ frame and glass panes, which were fabricated over a period of four months. Each pane weighs 127 pounds and is nearly 8.5 feet long. Hoisting the large panes to the top of the Rotunda dome posed a significant challenge. The installers bolted a winch to the scaffolding and secured suction cups to the glass to carefully raise each pane to the oculus. Etchings on the glass represent Jefferson’s original oculus, which was made with smaller, overlapping glass shingles because the technology did not yet exist to make the large panes that are currently being used. The approximately 2.5-inch overlap of Jefferson’s glass shingles is represented by a silk-screened pattern on an interior layer of the insulated glass.

Bob Desrochers

Bob Desrochers, a master clockmaker of Lititz, Pennsylvania, was brought in to consult on the work on the Rotunda clock, the official timepiece of the University, which has gotten an extensive facelift in the renovations. Jefferson had commissioned Boston clockmaker Simon Willard to construct the original Rotunda clock, and New York architect Stanford White commissioned E. Howard and Co., clockmakers of Boston, to recreate the timepiece. The Howard clock face, with a 55-inch dial face and 5 1/2 inch-bezel – the ring around the outside of the clock— will be preserved behind a new clock face.

Desrochers installs the hands of the north portico clock on the Rotunda. Craftsmen installed a new face, duplicating the original Howard clock face, but fashioned out of aluminum. The old clock face is preserved under the new one. New hands, recreating the Howard hands and also fashioned out of aluminum, have been installed. (The original Howard clock hands were replaced with simpler, wooden hands in 1960.)

The Rotunda clock had once been the master clock that controlled other clocks on Grounds and was linked to the bells marking the change of classes. Similar to a string of Christmas lights, if one bell malfunctioned, the entire system failed. One short circuit or break in the wire would cause the clocks to gain time rapidly or stop completely.

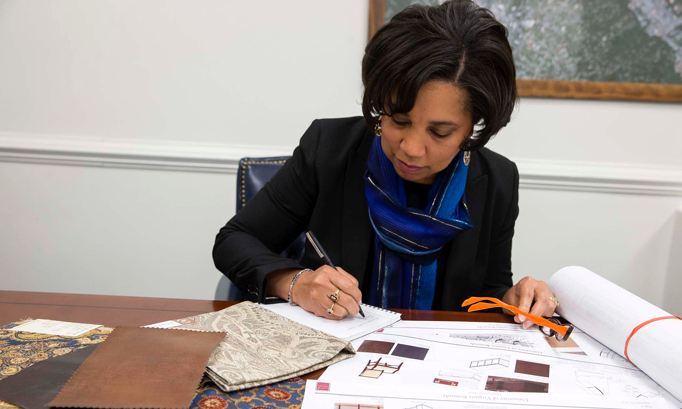

Sheri Winston

Interim Rotunda manager and assistant director of major events, Winston will oversee the operations of the renovated Rotunda, which is a center of University life, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a major tourist attraction. Jefferson designed the Rotunda as the library and a classroom building in the early life of the University. The library grew to fill the entire building before eventually prompting the construction of Alderman Library. After that, the Rotunda shifted to office space and meeting rooms for the Board of Visitors, the governing body of the University.

Winston examines upholstery samples for the renovated Rotunda. After the library moved from the Rotunda, there were fewer reasons for students to visit the building. When it reopens, the Rotunda will feature several permanent classrooms and expanded study space, and will host more social activities, which will return the Rotunda to the center of student life. There also will be new attractions for tourists, with a display of historic artifacts from the building in the Lower East Oval Room, plus a display of the rediscovered chemical hearth, part of the earliest chemical education curriculum in the country.

Sarita Herman

Project coordinator with the University’s Facilities Management Department, Herman is one of the construction professionals overseeing the Rotunda renovation, the first major work done on the building in nearly 40 years. The project encompasses installing new mechanical, electrical, audio/visual, media, and fire and life safety systems; replacing the roof and the marble column capitals; and creating an underground room beneath the east courtyard to house the building’s mechanical systems.

Herman looks over renovation production reports. She is one of a team that supervises and coordinates the construction for the University. Scaffolding which has covered the front of the south portico for much of the past year, has been removed and viewers can see the newly installed capitals and the renovated portico clock. Capitals on the building have not been visible since 2010, when workers installed protective covers over the old capitals after they started crumbling.

Noel Bird

The University’s Board of Visitors directed Stanford White to make the building fireproof. For this reason the cornices, which appear to be wood, are actually made of copper. Master plasterer Noel Bird, of John Canning Company of Cheshire, Connecticut, was brought in to work on the eagle that decorates the ceiling of the south portico. White frequently used eagles as motifs in projects he designed. The raptors were featured around the oculus in the Rotunda Dome Room in White’s Rotunda; in his design of the Pennsylvania Station in New York City, eagles were used around the exterior of the building.

Bird restored some of the feathers that had fallen off the plaster beaux arts eagle on the ceiling of the south portico. Bird also repaired cracks that had been covered over with many layers of paint. He reinforced the plaster of the eagle and secured it into place with screws. Bird said he was impressed that the figure was well-preserved, considering it has been outdoors. With the work on the eagle complete, workers will replace the remainder of the portico ceiling.

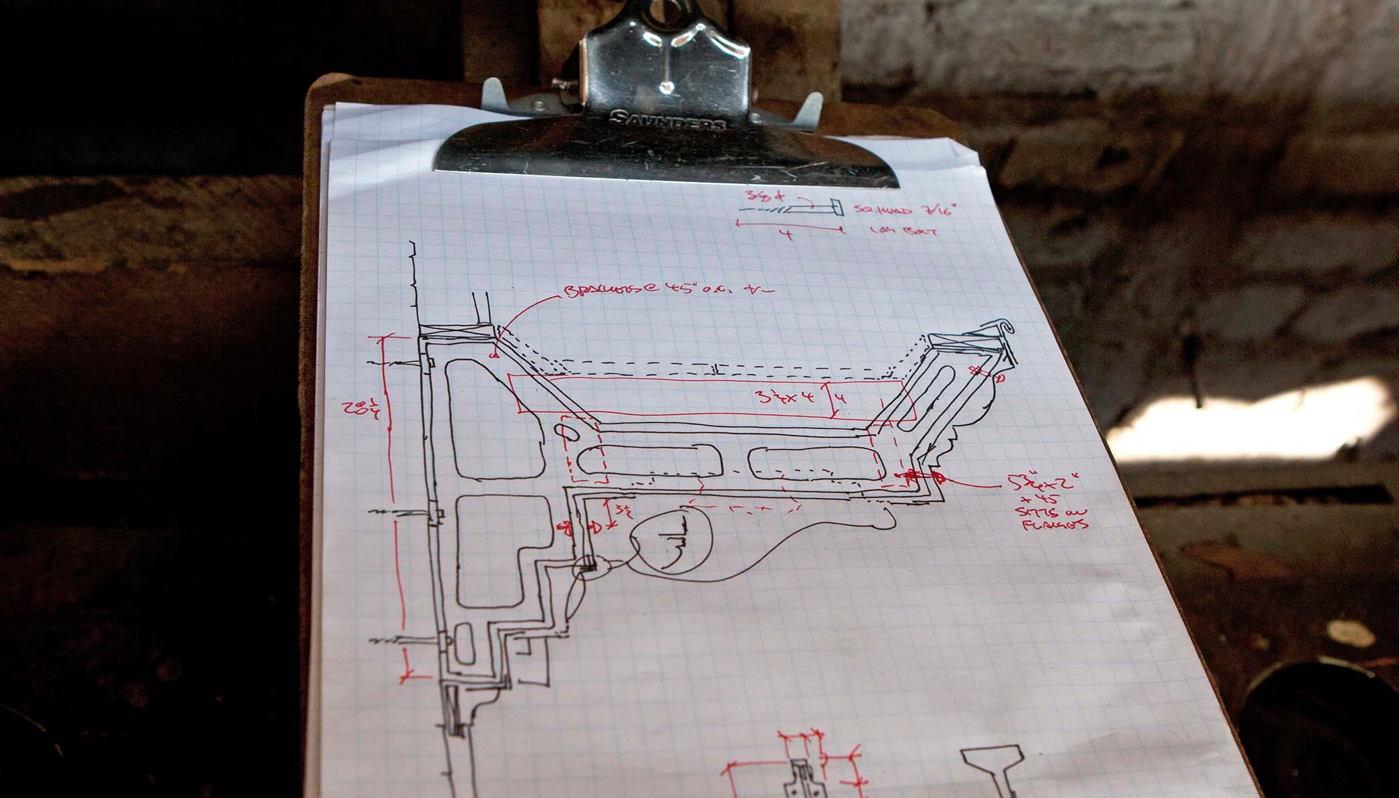

William “Billy“ Smart

Smart of Legacy Restoration and Construction LLC of Hillsboro, Ohio, was part of the crew that restored the cornices on the Rotunda. Legacy worked on the project in conjunction with Centennial Preservation Group of Columbus, Ohio. The crews removed the copper cornices, stripped the paint from them, repaired damaged areas and returned them to their original spots on the building.

The University’s Board of Visitors directed Stanford White, in re-envisioning the Rotunda after the 1895 fire, to make the building fireproof, so the cornices, which appear to be wood, are actually. When White recreated part of the Rotunda in the 1890s, the cornices were fastened to the Rotunda using cast iron brackets held in place by pintle hooks. At left, an early sketch shows the plan that Legacy workers developed to take the brackets down, refurbish and repair them, and then reinstall them on the exterior wall of the Rotunda. At right, the work in progress.