In 2009, on a visit to the University of Virginia, Australian artist Judy Watson saw the exhibit “Thomas Jefferson’s Academical Village: The Creation of an Architectural Experience,” curated by Richard Guy Wilson, professor of architectural history.

It was a transforming experience for her – and her art.

The fruits of that experience are currently on exhibition in the South Gallery of the Harrison Institute/Small Special Collections Library. The exhibition of six prints, “experimental beds,” is on view through May 11.

Born in 1959 in rural Queensland, Watson is a Waanyi woman of Aboriginal and European descent who grew up in suburban Brisbane. Her mother’s mother was an Aboriginal woman who married a white man.

To describe her heritage, Watson refers to the scene in the movie, “The Blues Brothers” in which Dan Aykroyd’s Elwood Blues asks the bartender at Bob’s Country Bunker what kind of music they play there, and the bartender replies, “Oh, we got both kinds. We got country and Western.”

Watson explains that, as an Indigenous person with a connection to ancestral land and knowledge, she is “country,” but that her education and training as an artist have been entirely “Western.”

“I am Indigenous and non-Indigenous,” Watson has said. “I fit somewhere in between. I embody the notion of two cultural frameworks occupying the same cultural space.”

Familiar with Watson’s work, Margo Smith, director and curator of the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection at U.Va., extended Watson an invitation to be artist-in-residence in a program funded by the U.Va. Arts Council. The Kluge-Ruhe Collection is the only museum in the United States solely dedicated to the exhibition and study of Australian Aboriginal art.

Smith obtained permission from U.Va.’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library for Watson to review Jefferson’s architectural drawings to create a series of etchings. In addition, Smith introduced Watson to key Jeffersonian scholars and researchers at Monticello.

In September 2011, Watson began working with copies of a selection of Jefferson’s drawings and other visual material at the Special Collections Library. During her residency in October, she worked on the proofs with Dean Dass, professor of studio art in the College of Arts & Sciences, and with advanced printmaking students, experimenting with the use of different images.

During her residency, Watson also visited Monticello to learn about the slave experience and Jefferson’s gardens. While showing her around the gardens, Leni Sorenson, an African-American historian at Monticello, unintentionally presented the artist with the title for Watson’s suite of etchings.

Sorenson mentioned that Jefferson called these gardens his “experimental beds.”

Sorenson explained Jefferson’s practice of experimentation in the Monticello gardens. He planted seeds collected from across the American continent by the Lewis and Clark expedition, and seeds from plants that had arrived with slaves from the Congo. Jefferson would then assess the usefulness and adaptability of the crops to Virginia’s climate.

For Watson, the title “experimental beds” for her series of etchings had another meaning, suggesting Jefferson’s alleged sexual relationship with the enslaved woman, Sally Hemings. Hemings’ children of mixed descent are reflected in Watson’s own family in Australia.

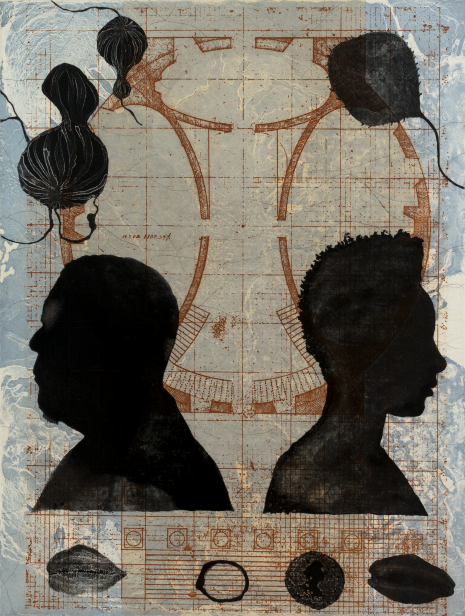

At Monticello, Watson photographed artifacts unearthed at Mulberry Row, where archaeological research has indicated that slave dwellings were located. In her six etchings, she incorporates drawings from these images of archaeological finds and vegetables from Jefferson’s gardens. In her work, she also uses the image of the elk antlers that hang in Monticello’s entrance hall, as well as silhouettes representing Jefferson’s slaves.

The silhouettes in Watson’s work are of Aboriginal artist and activist Richard Bell and African-American dancer Lindsay Jackson, both friends of the artist. They represent the parallels between slavery in the U.S. and Aboriginal people in Australia, who experienced similar treatment by white colonists. Aboriginal people were not considered citizens of Australia until 1967, when Watson was 8 years old.

These images are all overlayed over Jefferson’s architectural drawings of the Academical Village, which establish what Watson calls “the bones of the work, the literal foundations on which the images float.”

“I think Watson’s etchings are one of the most exciting things we’ve ever done at Kluge-Ruhe,” Smith said.

The Watson project was co-published by the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection, the artist and grahame galleries + editions in Brisbane.

Media Contact

Article Information

December 21, 2012

/content/jefferson-s-drawings-and-monticello-inspire-work-australian-artist