“Ban the box” policies are becoming increasingly popular around the United States as state and local governments try to end discrimination against job seekers with criminal records. Variations of the policy bar certain types or, in some cases, all employers from asking about an applicant’s criminal background on job applications and have gone into effect in 24 states, the District of Columbia and on most federal government employment applications.

Despite lawmakers’ best intentions, new research by the University of Virginia’s Jennifer Doleac shows these policies have unintended consequences that harm minority job applicants.

“I’ve done work on discrimination in the past and the first thing that jumped into my mind when I heard about ‘ban the box’ was, ‘This is going to backfire. This is just going to result in statistical discrimination against groups that are more likely to have criminal records,’” she said.

Doleac, an assistant professor of public policy and economics at UVA’s Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy, recently completed a joint study of the effects of “ban the box” policies with University of Oregon Associate Professor of Economics Benjamin Hansen. The results support her initial worries about the policy.

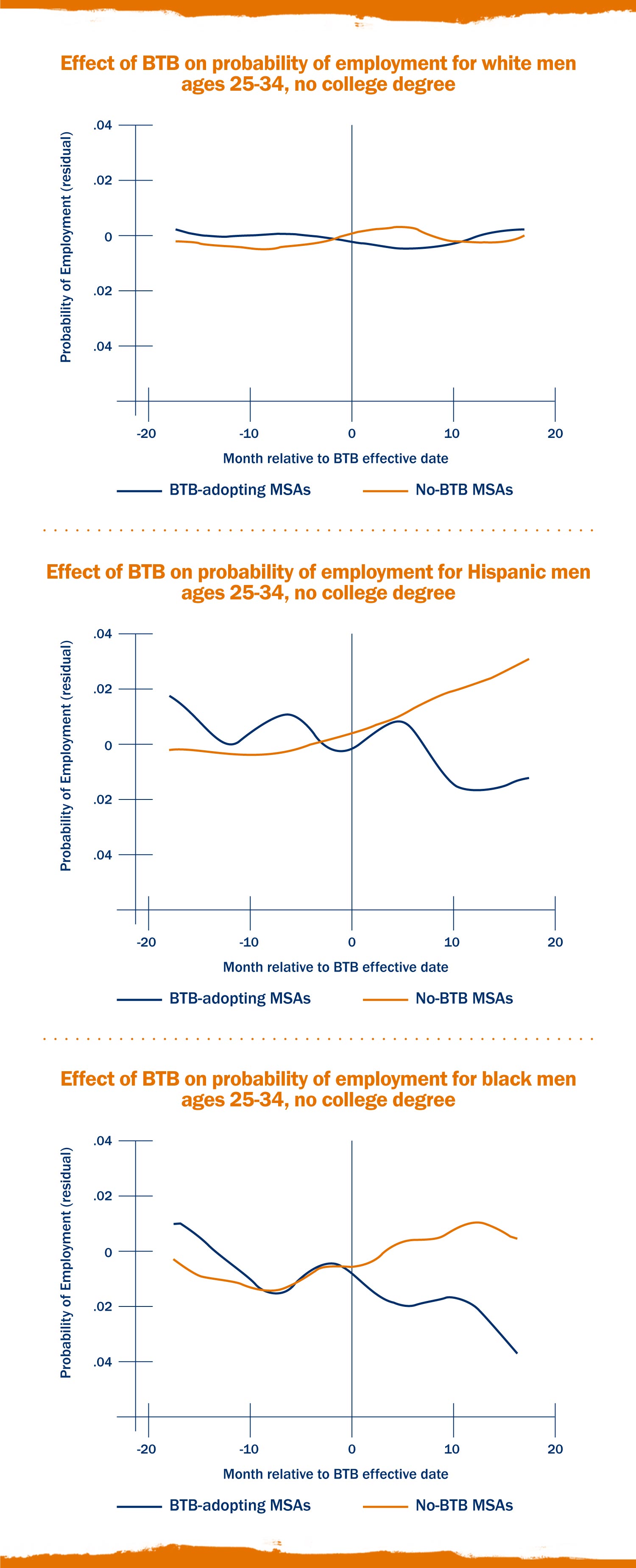

In areas where “ban the box” policies have been implemented, Doleac and Hansen found that the probability of employment for young black men without a college degree went down by 3.4 percentage points; for young Hispanic men without a college degree, it dropped by 2.3 percentage points.

Statistically, young, low-skilled, African-American and Hispanic men have higher rates of conviction than other demographic groups. When they can’t tell up front if applicants have a criminal record, employers often fall back on these statistics to broadly eliminate groups that they think, on average, are more likely to have a recent conviction.

This type of broad racial discrimination is of course illegal, but it can be hard to prove.

“Of course we should enforce our anti-discrimination laws, but we also need to acknowledge the reality of the world we live in when designing public policies,” Doleac said. “At the very least, we should avoid implementing policies that unnecessarily increase racial discrimination.”

The above graphs chart the impact of “Ban the Box” or BTB policies on the employment rates of different demographic groups across affected metropolitan statistical areas or MSAs.

The impact of “ban the box” seems to be part of a larger trend of unintended negative consequences of policies that limit employers’ access to applicants’ backgrounds.

“Basically, what we know about the impact of these types of laws is that providing more information about job applicants increases hiring of racial minorities, and taking information away decreases employment for those groups,” Doleac said.

Other studies have found that banning credit history checks disproportionately affects black job seekers and can reduce their chances of getting a position by up to 16 percent. There is also evidence that allowing drug testing actually increases the levels of employment for black men.

“The evidence from employer surveys suggests that they are most hesitant to hire people who have been recently incarcerated. I think that’s for a few reasons,” she said. “The more recent the incarceration, the better signal it is about what your current behavior is like. So if you were recently convicted of a crime, there’s a higher chance that you’re still engaged in criminal behavior than if you were convicted 30 years ago. The recently convicted also have a higher rate of recidivism.”

She added that employers may have legitimate concerns about how well a recent convict can perform their job. The high rate of recidivism in particular may cause concerns that someone with a prior conviction will be arrested again soon and unable to work consistently.

To combat the discrimination against convicts that “ban the box” was intended to help, without unintentionally hurting minority men without records, Doleac recommends a two-fold policy plan. The first goal, she suggests, should be to give employers more information, not less.

She believes that employers are discriminating against those with a criminal record because that record is somehow correlated with underlying characteristics they care about. For example, individuals with criminal records may have histories of violent or dishonest behavior, and on average might struggle with greater emotional trauma and have worse interpersonal skills. Providing opportunities for applicants to signal that they don’t have these problems – perhaps by having a local job-training program vouch for them could help them overcome automatic assumptions about their temperament and suitability.

“The other broad category of policies that would be better than ‘ban the box’ includes education and rehabilitation programs that would actually improve the underlying job readiness of this population,” Doleac said. “The reason that employers discriminate against people with records is that, on average, that group is less job ready than people without records.”

With these two broad guidelines in mind, Doleac is planning further research aimed at finding new, innovative ways to improve the lives of people with criminal records.

“I’m working now with [Assistant Professor of Education and Public Policy] Ben Castleman at [UVA’s] Curry School of Education on a project related to re-entry,” she said. “We’re designing and implementing a new tech-based intervention that we think will help individuals who are coming out of prison find stable housing, educational opportunities and employment, in order to improve re-entry outcomes.”

Media Contact

Article Information

August 5, 2016

/content/unintended-consequences-how-ban-box-backfires-minority-job-seekers