When the University of Virginia’s famed Rotunda was being built, Robert Battles, a free man of color, hauled more than 176,000 bricks and several tons of sand to the site in 1823.

Battles’ treks give a sense of the impact African-Americans made on the construction and early functioning of the University – a history overlooked for years in the telling of the University’s creation. You only have to look around the Academical Village to find more instances.

As the design team for UVA’s Memorial for Enslaved Laborers continues gathering ideas and sharing its work to “create a physical place of remembrance and a symbolic acknowledgement of a difficult past. … a place of learning as well as a place of healing,” existing sites and historical markers illuminate some of the rich African-American history on Grounds, from slavery to student leadership.

The President’s Commission on Slavery and the University, which spearheaded several groups’ efforts to create a memorial, also published a new walking tour map to coincide with last fall’s reopening of the Rotunda. Available in the Rotunda, it introduces sites on Grounds related to the work of enslaved laborers and relates some of the stories that have emerged from the commission’s and others’ research.

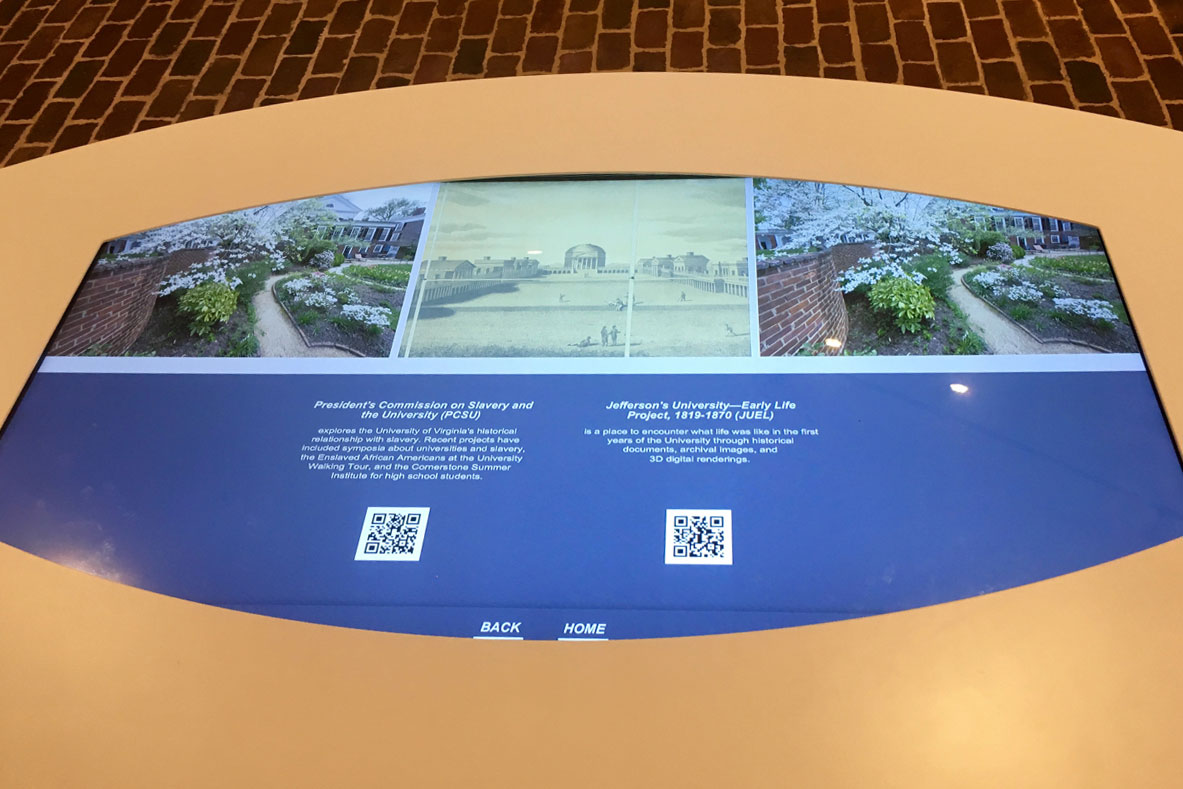

Here are 10 sites marking African-American history and stories at UVA – just a sample of the past that is coming to light. The commission’s website and the Jefferson’s University: The Early Life project contain many more stories about the people and the work being done to commemorate this early past.

Rotunda Visitor’s Center, Lower East Oval Room

The interpretive wall panels that now line the room include relevant details about slavery and the lives of the enslaved at the University. The main exhibit space for the visitor’s center in the Lower East Oval Room also has two touchscreen interactive kiosks that offer even greater detail about slavery and the enslaved people who helped build and maintain the University.

(Photo courtesy of President’s Commission on Slavery and the University)

Among the more than 300 people who worked on the construction of the Academical Village – black and white, enslaved and free – were these men who made some of the ubiquitous bricks, as the exhibit describes them: “An enslaved man named Charles was responsible for digging the clay and manning the kiln with the help of six enslaved boys rented out from John H. Cocke in 1823. Enslaved laborers named Dick, Lewis, Nelson and Sandy were also assigned to the brickyard, and worked long hours by the kiln.”

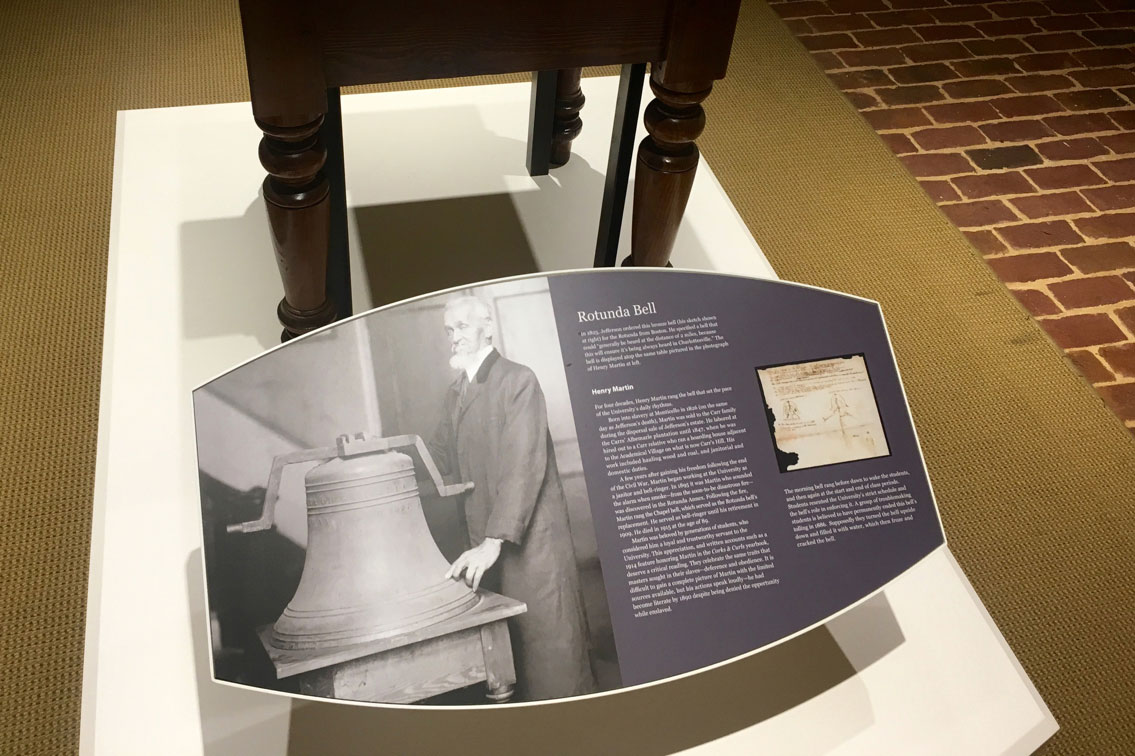

Plaque to Henry Martin

The plaque honoring Henry Martin, the University’s bell-ringer for 50 years, lies near the University Chapel, where today’s bells are automated. Martin was born into slavery at Monticello on July 4, 1826 – the day Thomas Jefferson died – and started working at UVA around 1847.

(Photo courtesy of President’s Commission on Slavery and the University)

Before the 1895 Rotunda fire, he rang the Rotunda’s bell hourly, starting at dawn. After the fire, the bell was relocated to the University Chapel. The main exhibit space in the Rotunda’s Visitor’s Center also has a tribute to Martin, who seems to have been much loved by students. He wrote a letter to the University in the 1890s consenting to let students tell his life story in the Alumni Bulletin or Corks and Curls, said historian Kirt von Daacke, co-chair of the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University.

The Crackerbox and McGuffey Cottage

Few of the buildings where enslaved people worked and/or lived remain intact, but two that have been modernized are the Crackerbox, behind Pavilion X’s garden and immediately adjacent to Levering Hall (Hotel F), and McGuffey Cottage, adjacent to Pavilion IX. The Crackerbox was a kitchen with dwelling space on the second floor.

The Crackerbox and McGuffey Cottage (Photos by Dan Addison, University Communications)

The large cooking fireplace has been partially bricked over to create a smaller fireplace, but a bread oven remains in place. Another small outbuilding known as the Mews behind Pavilion III also served such purposes.

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1963 Visit to the Grounds

The most recent recognition of UVA’s civil rights history is a plaque in Old Cabell Hall commemorating the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1963 speech there.

Siblings Wesley and William Harris donated a plaque commemorating King's 1963 speech at UVA. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

The plaque, installed Jan. 23, is a gift from brothers Wesley and William Harris, who both have deep UVA ties. Wesley, a 1964 graduate, helped bring King to Charlottesville for the historic visit, and his brother William served as dean of the Office of African American Affairs from 1976-81.

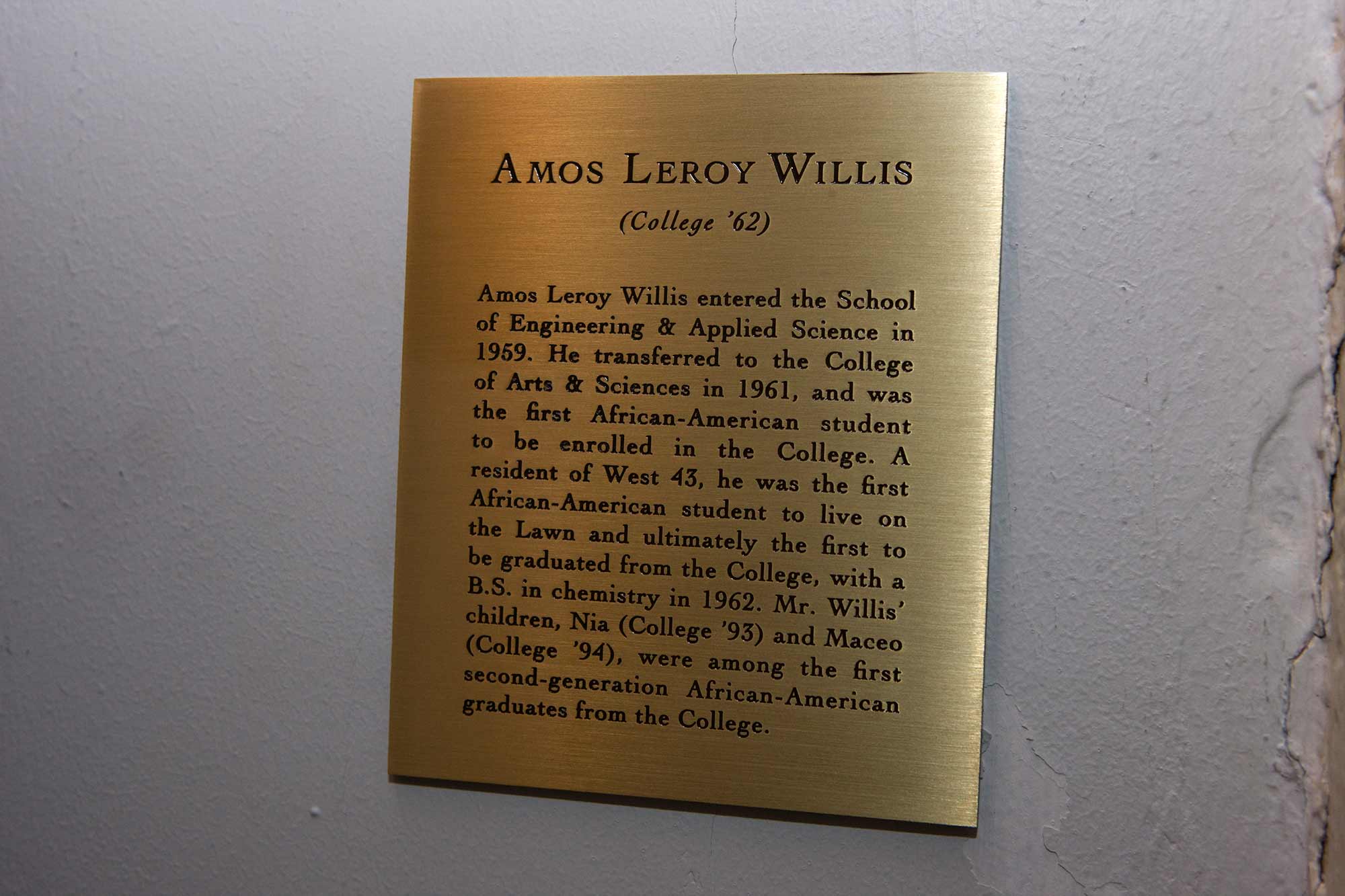

First African-American Student to Live on the Lawn

Amos Leroy “Roy” Willis was the first black student invited to live on the Lawn, and the first to earn a degree from the College of Arts & Sciences (in chemistry) in 1962. A plaque honoring him was put up at 43 West Lawn and dedicated in 2010.

Two of his children also graduated from the College, Nia in 1993 and Maceo in 1994. The plaque mentions their names as “among the first second-generation African-American graduates from the College.”

Catherine Foster Memorial and Display Inside Nau Hall

The small park at UVA’s South Lawn honors Catherine “Kitty” Foster, a free black woman who purchased the property in 1833. The site, once part of a community known as “Canada,” is believed to hold the graves of adults and children, including Foster and her descendants, which workers discovered during an excavation in 1993.

The outline of Foster’s home is preserved on Grounds that casts its shadow. (Photo by Jane Haley, University Communications)

Archaeological investigations eventually located 32 unmarked gravesites, evidence of a cemetery that served the community – which included both white and free black members, many working in labor and domestic jobs for UVA until the early 20th century. As part of the planning for the University’s South Lawn, care was taken to preserve the outline of Foster’s home with a structure that casts its shadow, as well as the location of the cemetery and portion of an original cobblestone walk found on the site.

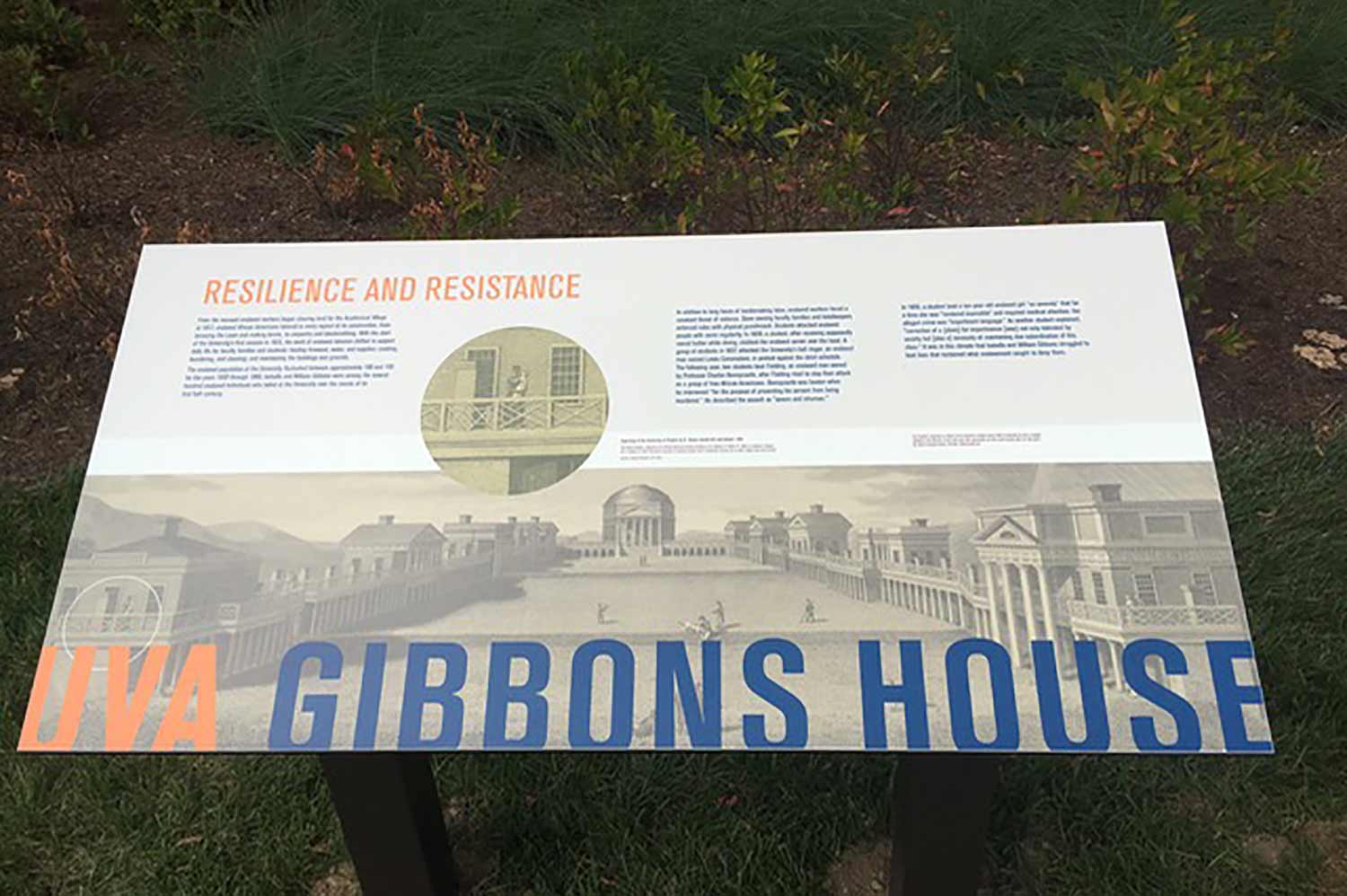

Gibbons House

William and Isabella Gibbons were husband and wife, enslaved by different professors and living in different pavilions in the mid-19th-century University. Once emancipated, Isabella became a teacher at the Freedman’s School – now the Jefferson School – and William became a minister at Charlottesville’s oldest black church, First Baptist.

Panels telling the Gibbons’ story are outside and inside the dorm that now bears their name.

UVA’s newest dormitory, the five-story Gibbons House, houses 200 students. Panels telling the Gibbons’ story are located outside and inside the building.

“One of the recommendations of the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University was to name one or more UVA buildings after enslaved persons who were connected to the life of the University,” UVA President Teresa A. Sullivan said.

African-American Burial Site Near the University Cemetery

Workers discovered a burial site just north of the walls of the University Cemetery about four years ago, during an archaeological survey in advance of a planned expansion of the cemetery. Archaeologists identified 67 mostly unmarked grave shafts, which they said likely contained the remains of enslaved and possibly post-Emancipation African-Americans. The graves were left undisturbed.

The University held a ceremony to honor the site and souls buried there in October 2014 as part of the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University’s national symposium on “Universities Confronting the Legacy of Slavery.”

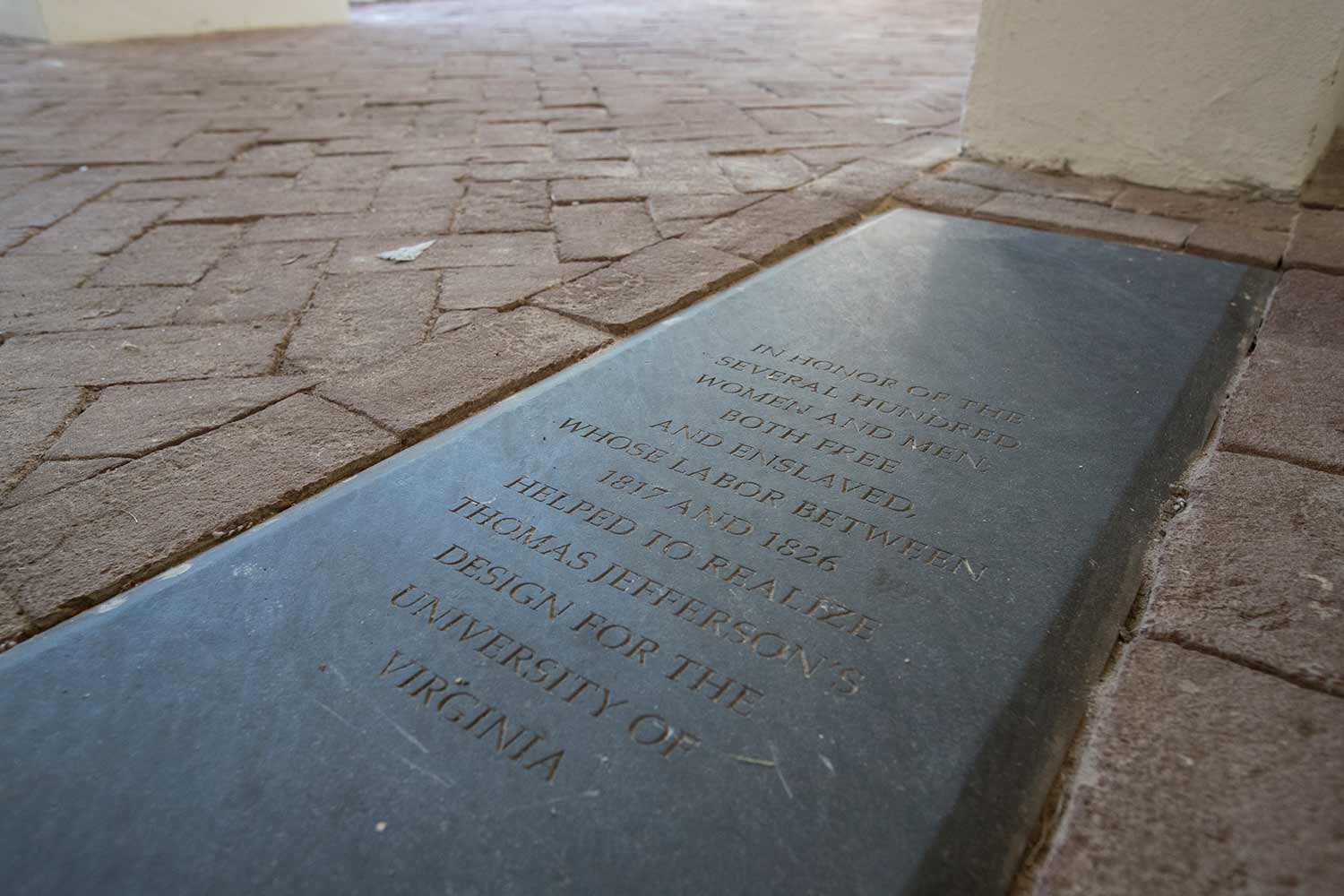

Plaque to Laborers

In February 2007, the University’s Board of Visitors approved the installation of a slate memorial embedded in the brick pavement of the passage under Rotunda’s south terrace to honor the laborers, both enslaved and free, who helped to realize Jefferson’s design for the Academical Village.

(Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Eventually, students, faculty and alumni let the administration know the plaque seemed an inadequate tribute. Endorsed by the Board of Visitors, the Memorial for Enslaved Laborers design team, with the input of many constituents, seeks to remedy that situation.

Media Contact

Article Information

February 27, 2017

/content/10-places-grounds-rediscover-black-history