In an alternative universe somewhere, the University of Virginia has a chapel on the Lawn. Memorial Gymnasium is over on Mad Bowl. Physics students take classes in a striking, modernist building that almost seems to float. This version of Grounds has a 12-story dorm on North Grounds near the Law School.

And there’s no Rotunda.

For 200 years, architects, University leaders and builders have been assembling the UVA we know today, building by building, chasing an idea that Thomas Jefferson laid out at its founding: that the University’s physical presence embodies the education of its students.

The original Jefferson-designed Academical Village is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the enduring heart of Grounds, but the University has been expanding beyond it almost since its completion. Over the centuries, the custodians of that growth have taken care to build in the spirit of “Jeffersonian architecture” – even if opinions sometimes differed on what exactly that means.

As a result, the University’s history is replete with designs for buildings that were never built and alternative proposals for ones that were. Some were done by famous architects who devoted years to plans that never quite came together. Others were fanciful suggestions and quick sketches, more thought experiment than serious construction proposals.

Taken together, these snapshots of a Grounds-that-could-have-been illuminate ideas that still drive the University’s future: Architecture matters here, and planners plan for the long run.

The Keeper of the Records

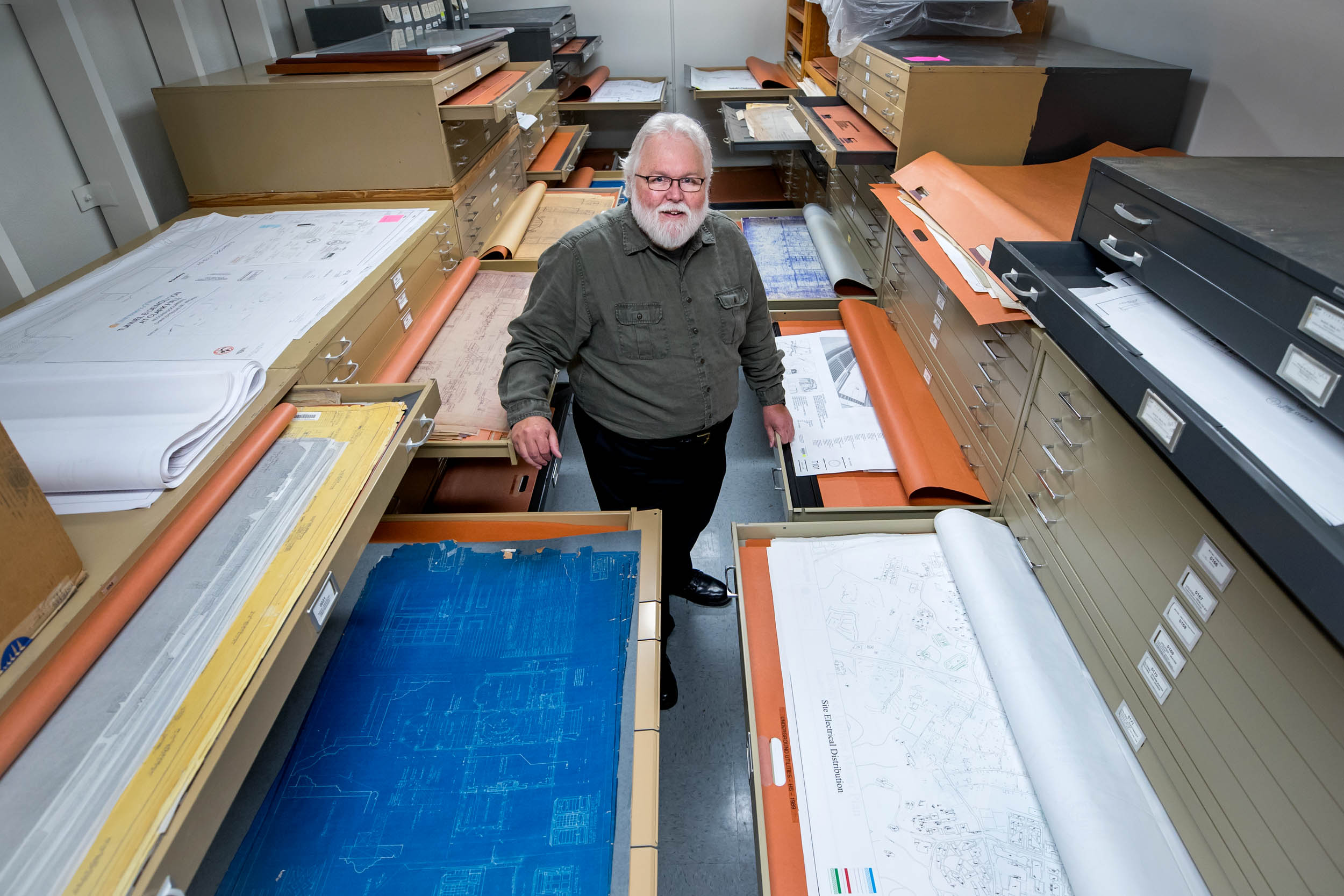

Tucked away in a long, narrow, climate-controlled room in a Facilities Management building off McCormick Road are rows of file cabinets filled with large flat folders. They hold a large part of the records of the University’s architectural history.

“The oldest one we have here is Fayerweather Hall,” Garth Anderson said on a recent afternoon, sliding open one of the drawers and pulling out a blueprint from the 1890s.

Now home to the McIntire Department of Art, Fayerweather Hall was originally built as a gymnasium.

Anderson is the man behind an extensive database of records on UVA facilities, a role he assumed almost by happenstance.

Anderson came to UVA in 1984 to supervise a clinical investigation lab in the Health System for the blood bank. This was in the early days of computing, and he got his hands on an IBM XT to replace the adding machine he’d been using. Before long, he’d taught himself to assemble and maintain a database.

About 12 years later, when the lab closed, Facilities Management was confronting a data problem of its own. The blueprints for all the buildings on Grounds built since the late 19th century – proposals, early designs, finished products and more – were kept rolled in tubes in a jumbled closet without any sort of index.

“If somebody wanted a particular record of a building on Grounds, they had to get in there and root around until they found it,” Anderson said. “I said, ‘I can do a database.’ I’m not a librarian, but I think like one sometimes.”

After years of work, that database is built and the records organized, both in physical form and in a digitized archive.

The project also put Anderson in closer touch with the University’s academic life. He’s worked closely with students on undergraduate research projects, helped doctoral candidates run down records and collaborated with faculty in the School of Architecture and elsewhere.

Garth Anderson manages an extensive database of building designs that includes hundreds of years of building plans. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak, University Communications)

“Garth earned a prominent place in my acknowledgments,” said Philip Herrington, an assistant professor of history at James Madison University who completed his Ph.D. at UVA and recently published an architectural history of UVA’s Law School.

Anderson also realized he likes following the historical breadcrumbs in the records.

“It requires a little investigative work that I love,” he said. “You start to get acquainted with the architects and the designers of the different buildings, and you start to turn to other sources to find out more about them.”

That itch to find out more also makes him a really good tour guide for a University that doesn’t actually exist.

Academical Village, v.1

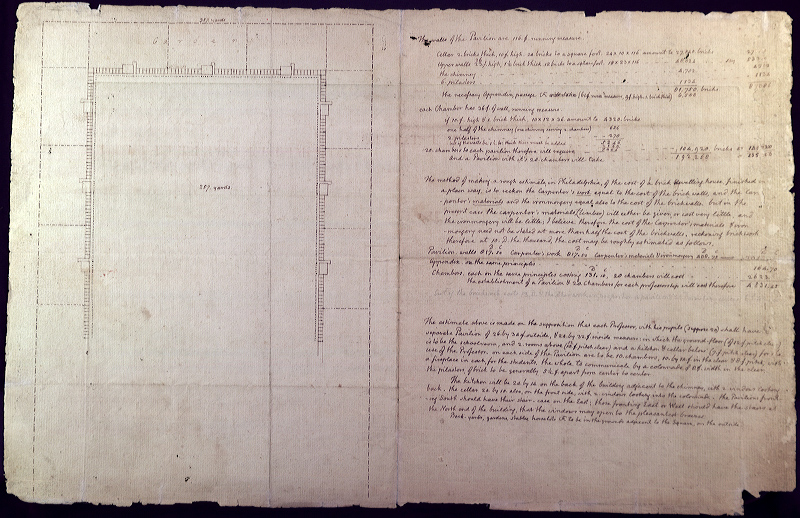

One of the first examples of alternative design plans that Anderson cites isn’t in his archive and is actually older than the University itself.

In 1814, Jefferson produced the first set of sketches for what would become the University of Virginia. Some features are familiar: a series of pavilions created a large “U” shape with a central Lawn or green space.

But the details are very different. For one, there was no Rotunda, just three pavilions facing down the Lawn.

Richard Guy Wilson, Commonwealth Professor of Architectural History in UVA’s Architecture School, is quick to point out that these sketches weren’t actual plans. They were developed before there was a site, years before the first workers – including enslaved laborers – would begin building the University after the laying of the cornerstone of Pavilion VII in 1817.

This early sketch had three buildings fronting the Lawn instead of the Rotunda and was made long before an actual site developed to house the University. (Source: Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library)

“In all architecture, the site actually determines what the buildings will look like,” Wilson said. “This was more of a scheme. He came up with this idea of the Academical Village, which came from ideas he’d had floating around for a number of years.”

These first sketches called for nine pavilions on a flat site, with expanse in the middle that stretched 257 yards across. (The actual Lawn is only about 188 feet across.) Perfect, Wilson said, for the flatlands of the Midwest or Tidewater. Not perfect for the rolling hills of Central Virginia.

Some of the early sketches were done in letters Jefferson sent to correspondents such as William Thornton and Benjamin Henry Latrobe asking for input and ideas.

“The reason he was writing them was that he’d recently sold most of his books to the Library of Congress, and that included his architecture books,” Wilson said. “So he needed some help.”

In one letter back to Jefferson, Latrobe suggested that the center building ought to be a domed structure. He apparently also sent a sketch of the idea to Jefferson, but that record is lost to history, Wilson said.

“We should keep in mind that Jefferson had a bug for domes of the worst order, and had been asking Latrobe endlessly about domes,” Wilson said. “So this played right into his hands.”

As the University’s creation progressed and an actual site was chosen, the plans evolved into what we know today. The three imagined pavilions at the front of the Lawn became the Rotunda; the Lawn narrowed and the ranges appeared on either side.

“In the end, the building site rules all,” Wilson said.

Modernism on Grounds

The history of new buildings beyond the Academical Village is one of good stewardship and strong opinions. As University Architect, Alice J. Raucher is keenly aware of the forces that go into a new structure here, and she sees part of her job as making a marriage of sorts between the architect and the University.

On the one side, architects need to be free to bring their own vision to a project. But new buildings on Grounds have to be understood as being part of the comprehensive whole, and they aren’t necessarily vehicles for radical personal design statements, Raucher said.

“We need architects that can put forward something fresh, but also understand our legacy and work within it,” she said.

Two of Anderson’s favorite unbuilt buildings date to the middle part of the 20th century, when the University was grappling with how to stay current on modern design trends while maintaining a sense of connection to its Jeffersonian origins.

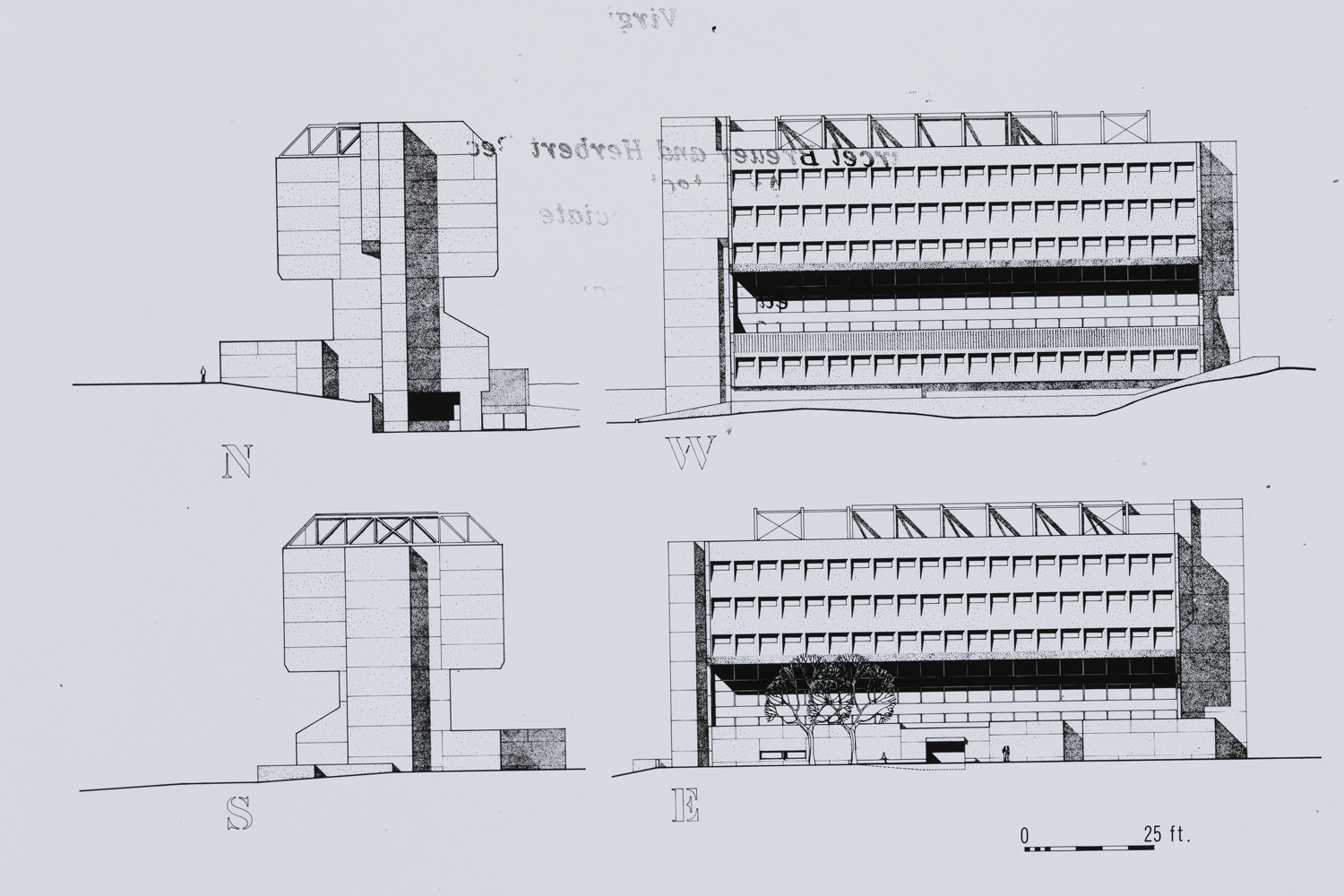

In the 1960s, architect Marcel Breuer proposed a building design for the Physics Department that had upper stories that cantilevered out wider than the base.

The building Marcel Breuer proposed to house the Department of Physics. (Source: Archives of American Art)

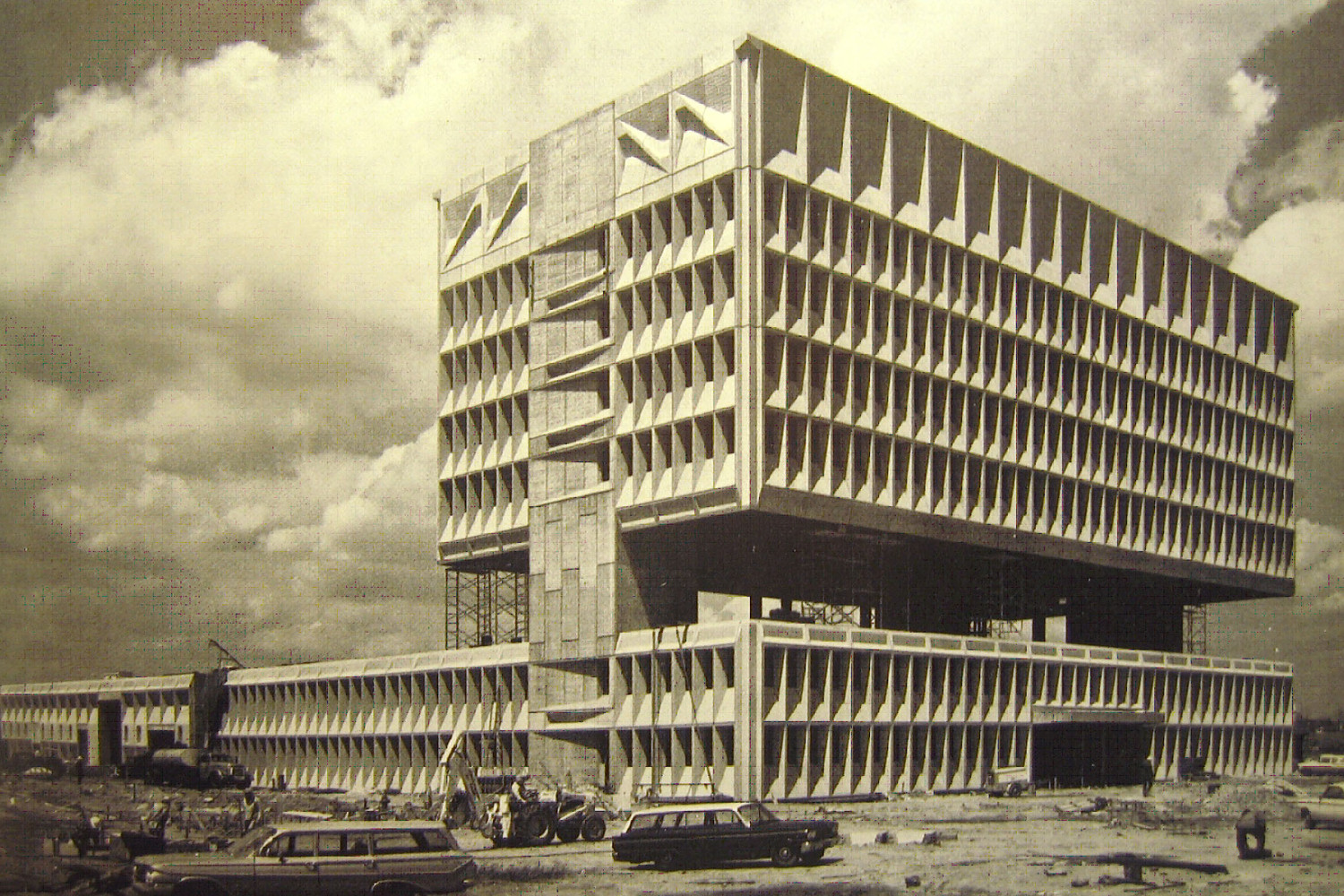

The design was a bit too far out for University planners at the time, who opted for a more conservative building. But Breuer later built a similar – though not identical – building as the headquarters for the Pirelli Tire Company.

Breuer later designed and built the Pirelli Tire Company headquarters, which shared many similarities with his design for UVA. (Source: Imgur)

A few years earlier, a similar fate befell a proposal for a chemistry building done by architect Louis Kahn. At the time, the Department of Chemistry was located in Cobb Hall, just off the Lawn. Lab chemicals had worn through many of the pipes in the building, and the department desperately needed something new, said Brian Cofrancesco, a 2011 architectural history graduate who researched the Kahn proposal extensively in his student days.

Kahn was then an up-and-coming architect who had done some work for the University of Pennsylvania. Though he was a modernist, Kahn had studied neoclassical design, and he took the idea of fidelity to Jeffersonian principles seriously, Cofrancesco said.

“In 1961 he actually stayed in Pavilion VII, studying what he called the ‘nuances of Jefferson’s Lawn.’”

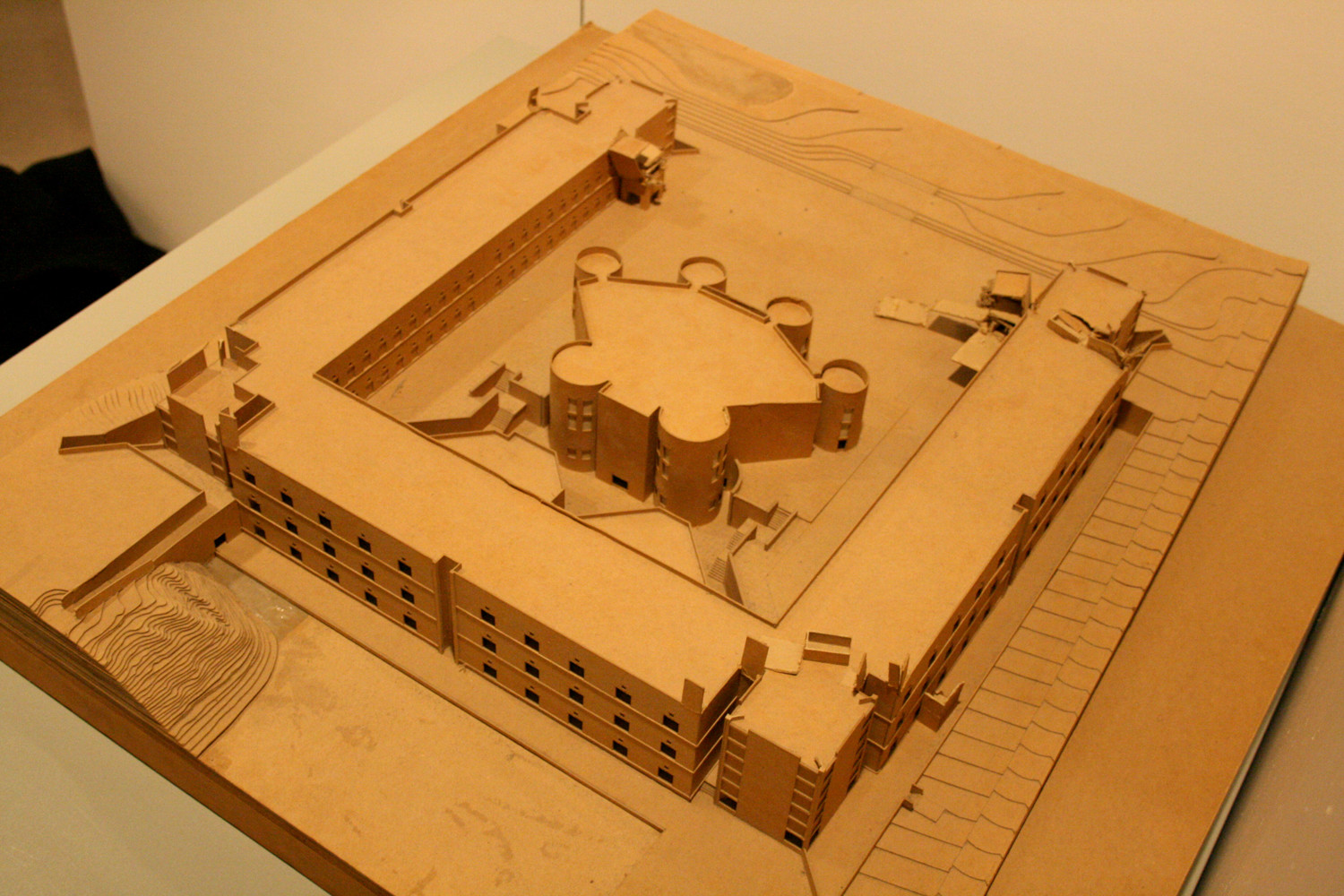

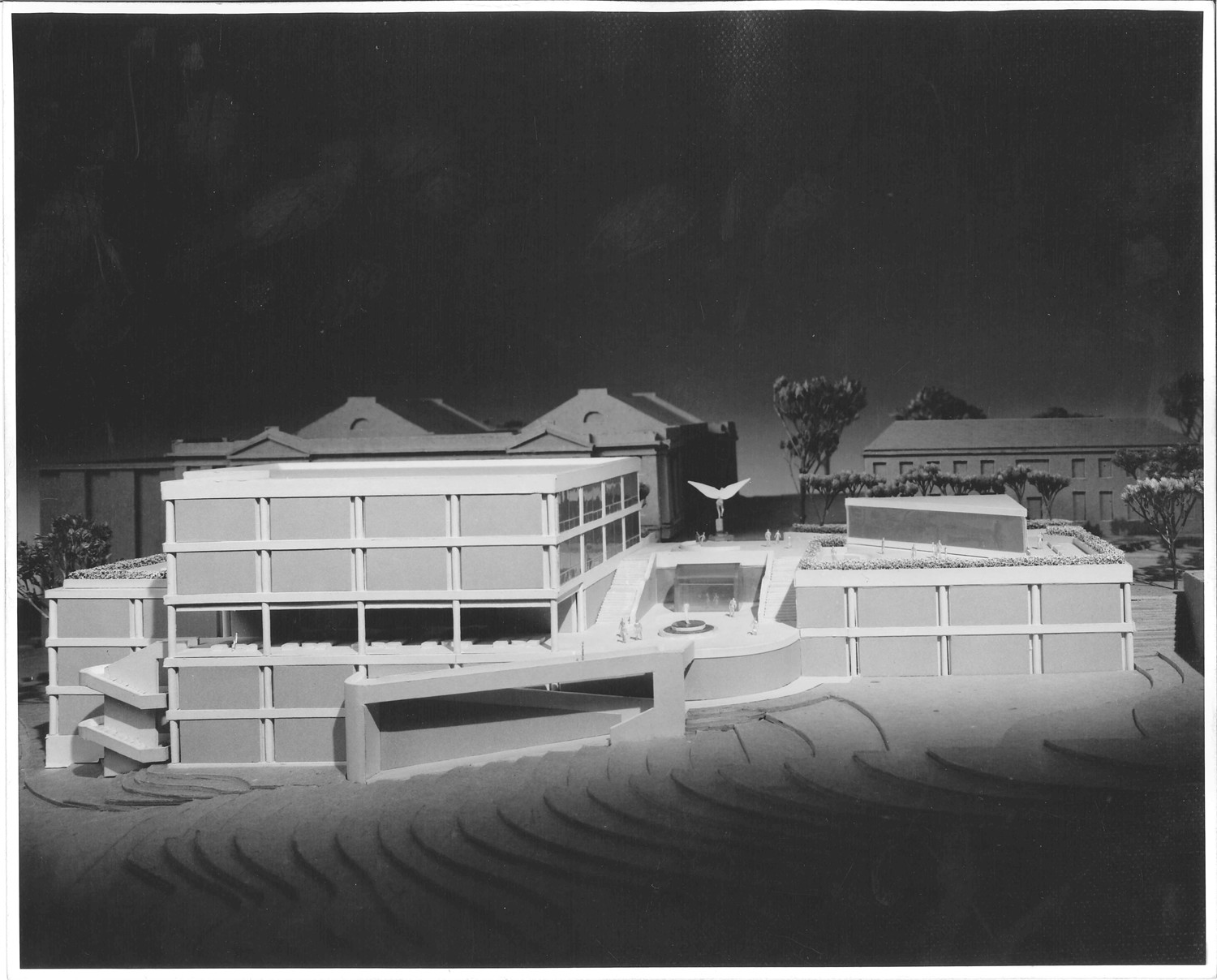

Kahn eventually delivered a design of a U-shaped building with an open end facing McCormick Road, with an enclosed amphitheater in the middle of a large courtyard.

A model of Louis Kahn’s Chemistry Building for the University of Virginia is housed with his papers at the University of Pennsylvania (Contributed photo by Brian Cofrancesco)

“In a way, it’s reminiscent of the three-sided Lawn and an open end,” Cofrancesco said. “It had at its center this kind of communal space of learning – just like putting the Rotunda at the center of the Academical Village. The wings of this building were going to be three stories tall, with the lower levels as labs and work spaces.”

In the end, the edgy design (and accounts of Kahn being less-than-responsive to communication and deadlines) caused the University to abandon the plans after nearly three years of development, Cofrancesco said. And not everyone liked the design. At one point, an architectural committee member assessed the proposed building as “cold, forbidding and prison-like,” he said.

“The president of the University, Edgar Shannon, said that calling Kahn to fire him was one of the hardest things he’d ever had to do,” Cofrancesco said.

Both Breuer and Kahn are important modernist architects, and the fact that they were not able to forward their designs at UVA is neither a reflection of their talents nor a sign that the University was too conservative in its ambitions, Raucher said. Her own professional history – both as current custodian of the University’s architectural integrity and her past as an academic and as an architect in the private sector – equips Raucher to see both sides of the relationship.

“Part of my job is to make a union between the University and architects so they can be successful on Grounds,” she said. “It’s not about having the next newest thing – I don’t believe in architecture as the latest fashion. Our architecture is civic in nature, and stands the test of time. And we have our iconic structures already: the Rotunda, the Lawn. Whatever we build today has to serve the University in that context, and then prepare us for the future.

“That’s not to say that we can’t have interesting, thought-provoking buildings unto themselves – I hope we do – but there are a lot of things that play into our selections.”

Location, Location, Location

Some of Anderson’s other favorite alternate building designs are notable not for what they looked like, but for where they would have gone. One was a proposal for the University Chapel that placed it on the Lawn.

Jefferson’s decision to make a university free from religious affiliation was controversial in its time, and beginning almost immediately after his death there was a concentrated effort spanning decades to build a church or chapel on Grounds.

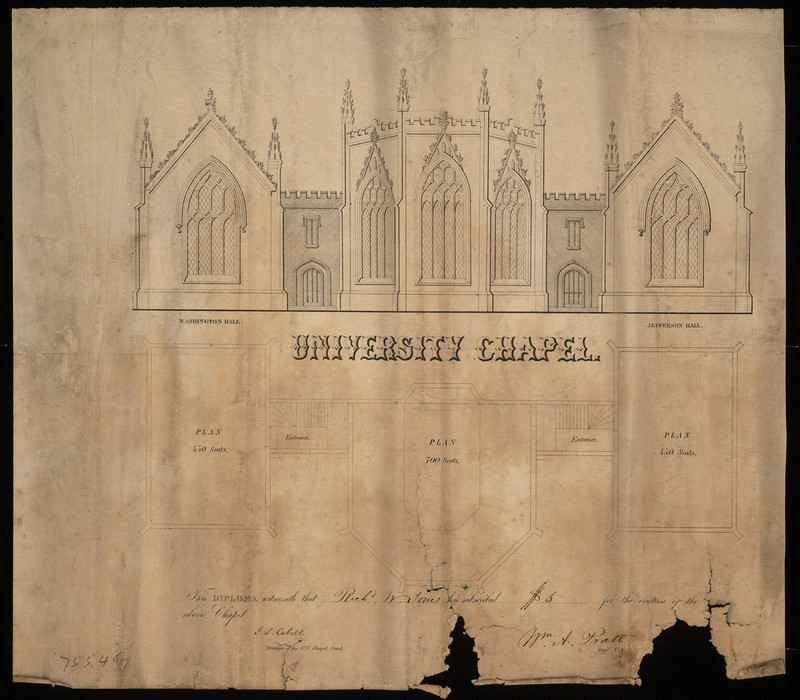

One of those proposals came from William Abbott Pratt, an architect hired in 1858 as the University’s first superintendent of buildings and grounds. That same year, Pratt proposed a design for a Gothic chapel built on the south end of the Lawn. He produced an elevation drawing to sell subscriptions to finance the building – several groups worked to raise funds for a religious building on Grounds during those decades, Anderson said – but it was never constructed.

It’s not clear where exactly on the Lawn this version of the chapel would have been built. (Source: Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library)

The actual chapel, built decades later northwest of the Lawn, was a factor in another building on Grounds that was originally proposed for a different spot.

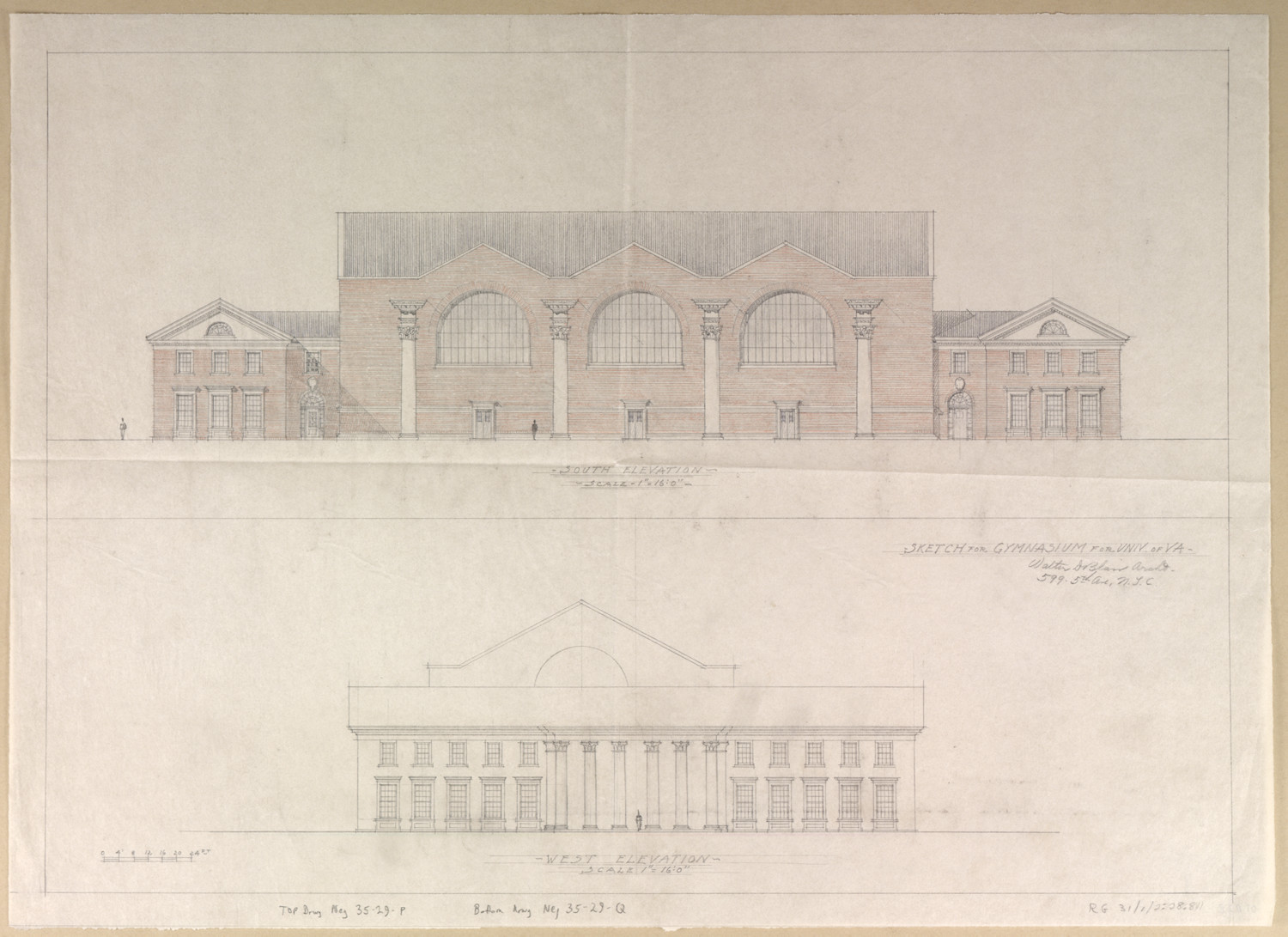

Memorial Gymnasium sits off Emmet Street at an angle slightly off from the road (the roadway came later and the building is actually oriented to be parallel to the Lawn), but an early 1922 proposal for the building placed it at the north end of Madison Bowl off Rugby Road, Anderson said.

That plan called for a three-bay design instead of five, and was done by a New York architect and UVA graduate named Walter Dabney Blair.

“If you look at a photo of Penn Station, it has a giant attic space that sits above providing the light into the massive waiting room – and this is a variation of that,” Anderson said.

This version of Memorial Gymnasium was similar in design to the one actually built, though the actual version includes five peaked bays instead of the three pictured here. (Source: Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library)

When the site moved to its current location, there were plans for a walkway and promenade that passed directly through where the chapel is located – planners at the time assumed the building would be removed, Anderson said.

A Rocky Process with Good Result

Perhaps one of the most contentious building design processes in the University’s history involved Clark Hall, which sits at the bend of McCormick Road and was completed in 1932 as the home of the School of Law.

Herrington studied the architectural history of the Law School extensively for a recent book published by the University of Virginia Press.

Many people played a role in the creation of Clark Hall, Herrington said. While the University’s Architectural Commission, which included Blair, designed the building, it had to satisfy overlapping, and at times competing, interests. Edwin Alderman, the University’s first president, and the Board of Visitors were deeply involved in the project. And the Law School’s dean and faculty had expectations for the new building they weren’t shy about expressing, he said. Add a wealthy donor, William Andrews Clark Jr., and there was no shortage of differing opinions.

One complicating factor was that the University was concerned about keeping its new, large buildings to the north and west visually subordinate to the original Academical Village, Herrington said.

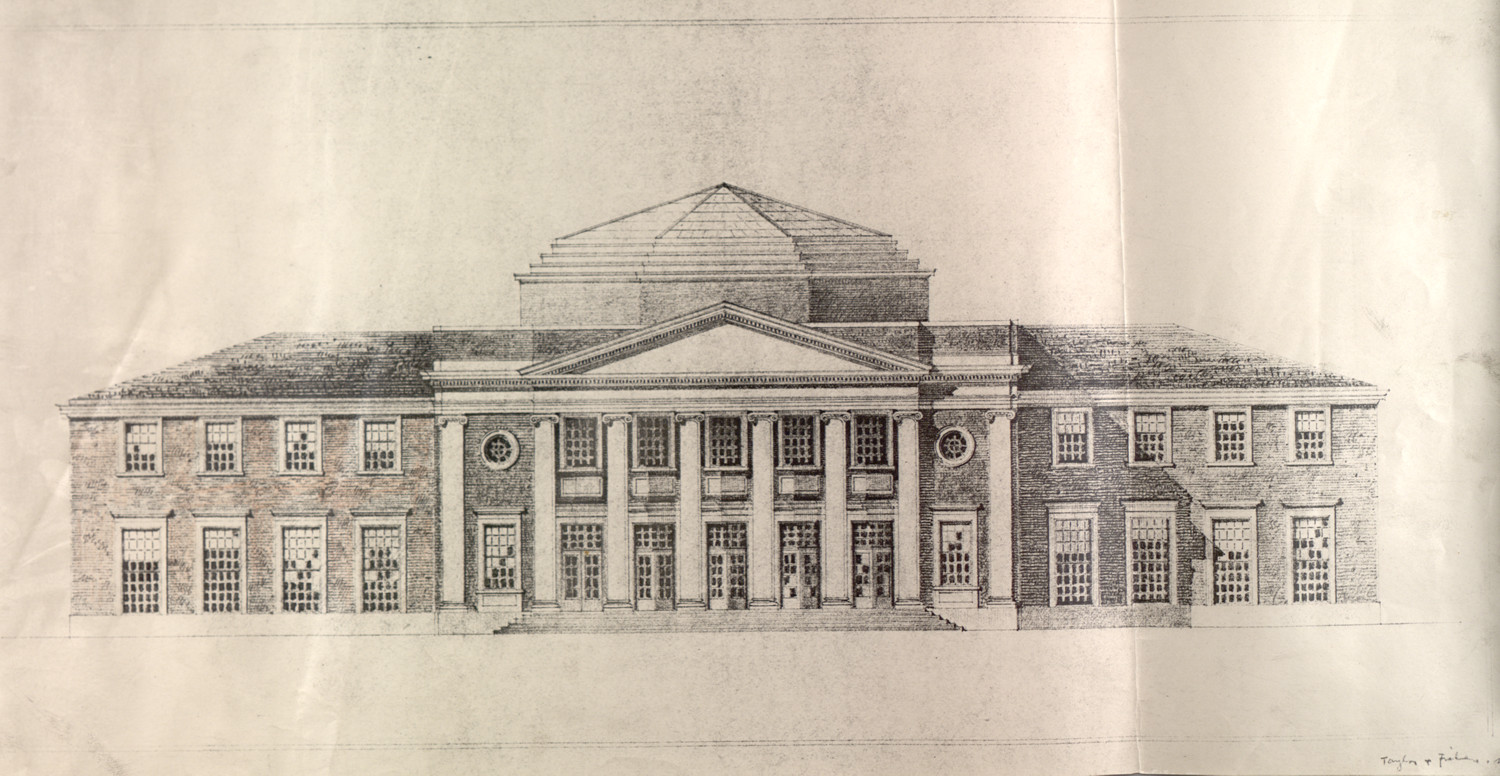

“One of the rejected plans for the new law building was a hulking mass of a building that had a very large octagonal dome,” Herrington said. “This design failed in part because it was so out of scale with the rest of Grounds, and its dome would have competed with the Rotunda.”

One of the rejected designs for Clark Hall called for a large dome.

“Clark Hall offered the Law School and the University an opportunity to assert their national prominence. There was a real fear in the period between the wars that the University was losing ground to other colleges and becoming a regional institution. So the question was, ‘How do you build something that evokes the local and familiar while also making it impressive?’” Herrington said. “The back-and-forth is funny in retrospect. The president and Board of Visitors wanted a ‘monumental’ building, but for months no one could agree on how to accomplish this. One member of the Board of Visitors dismissed a design for having wings; he said that a monumental building would never have wings. President Alderman thought one plan looked more like a post office than a law school. The architects frequently got upset because they felt like they were always starting over.”

In the end, though, the building design that the president, the Board of Visitors and the Law School agreed upon wasn’t that different from the commission’s original proposal, and Clark Hall is now one of the finest post-Jefferson structures on Grounds in terms of its proportions, materials and details, Herrington said. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2008.

Herrington’s book also traces the history of the Law School’s move to North Grounds – where one proposal called for a 12-story dormitory between the new law and Graduate School of Business buildings. He said the research process underscored for him the depth of emotion involved in the building process at UVA.

“I can’t imagine another American university where people feel so invested in the look of the campus,” he said.

Other alternative building designs on Grounds include this proposed version of Clemons Library.

For Raucher, that sense of emotional investment in the University’s physical presence is an asset that helps guide future projects, including upcoming transformations of the U.S. 250/Ivy Road approach to Grounds from the west, the new student-oriented neighborhood at Brandon Avenue, or the new building for the contemplative sciences.

“The style of the architecture is often used to describe what is, or isn’t ‘Jeffersonian,’” she said. “Jefferson was certainly looking at the historic buildings of Palladio for an architectural style, but he was also keenly aware of contemporary buildings of his time. It’s really about the ability of architecture to teach, and the ability for architecture to make use of technological advancements.”

We also can’t forget that the architecture of the University would not exist without the landscape that binds the Grounds together and gives it its unique identity, she said. The Lawn would not exist without the Colonnade and the rooms, and vice versa. “Our buildings are always understood relative to the landscape they inhabit, which provides the connectivity we try to achieve in every project.”

As plans for new projects come together, Raucher is also mindful that design choices now will affect students and faculty for centuries, and knows it’s important to get them right.

This drives the professionals of the Office of the Architect, who represent architecture, landscape architecture, land-use planning, space planning and historic preservation, she said. An integrated design approach ensures the careful stewardship of the historic Grounds and the thoughtful growth of the University for the next century.

“The heart and soul of the University will always be the Academical Village and the Rotunda; there’s nothing threatening that. It’s our responsibility to steward that for future generations,” she said. “But it’s also our job to lay the groundwork for future generations and build upon that strength.”

Media Contact

Article Information

March 22, 2017

/content/uva-grounds-could-have-been