Beginning this month, employees at a Wisconsin technology company called Three Square Market will have the option of having a microchip implanted under the skin in their hands, between their thumbs and forefingers.

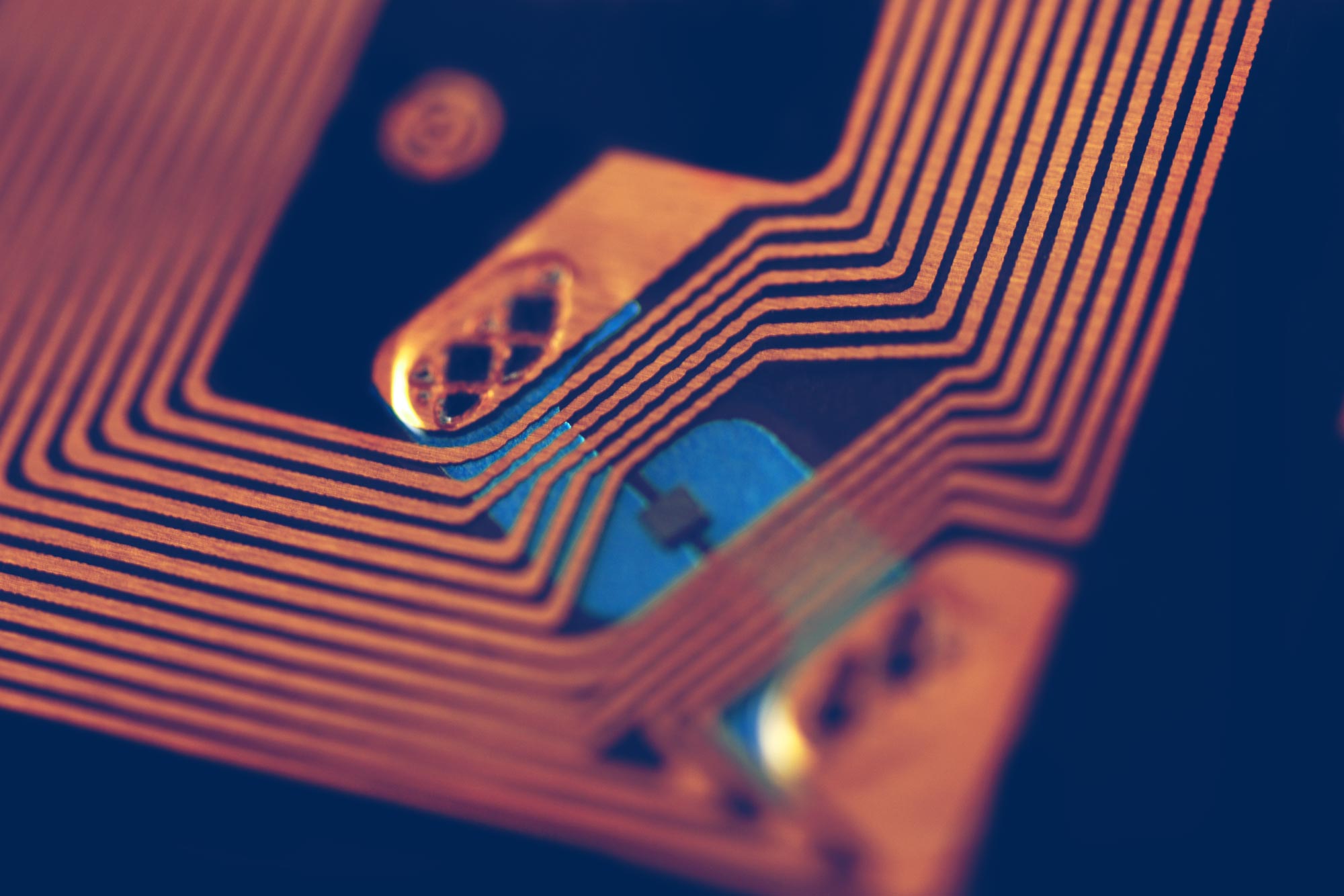

With the implants, functions that can be controlled by radio frequency – such as unlocking doors, buying snacks in the company cafeteria or logging onto company computers – can be handled with the simple wave of a hand where the chip is inserted.

Pretty cool technology for some. Kind of terrifying for others.

Rosalyn Berne said she was “not at all surprised” by Three Square Market’s microchip plan.

Rosalyn Berne, an associate professor of science, technology and society at the University of Virginia, expects strong reactions on both ends of the spectrum. And Berne, a bioethicist who explores the intersecting realms of emerging technologies, science, fiction and myth, said there is plenty of fodder for both camps on this one.

UVA Today caught up with Berne, who teaches in the Department of Engineering and Society in the School of Engineering and Applied Science, to explore some of the ethical and technical issues brought to the fore by the emergence of implantable technology.

Q. What was your reaction to the news of a company offering these implants, which it claims are safe, not trackable and use encrypted data?

A. I was not at all surprised; in fact, it was just a matter of time. Implanted devices have been used in farm animals for a while, and RFID chips with GPS capacity are commonly implanted in personal pets for tracking purposes. Although not implanted, it has been standard protocol for a nearly a decade for many hospitals to equip newborn babies with an RFID chip attached to a bracelet on their ankles.

As for the near-field communication, or NFC, technology that Three Square Market will be implanting, how many would agree to do so without such reassurances – that the implants will be safe, unable to be tracked and used with encrypted data? The question is how, once such the implants become widely accepted and used, such devices will evolve in their capacity and application.

Once established as the norm, and used with a sense of ease for the benefits and conveniences an implant provides, then technological “improvements” and “updates” will be likely. Iterative changes may be welcomed, and bring little resistance from their user. Technological history bears that out.

Q. News of this kind tends to polarize people. Why is that?

A. With novelty to the body, there comes ambiguity, fear, excitement. A knee replacement, for example, is one thing; it replaces a human body part that was already there at birth. An NFC device is another – embedding as an augmentation, in order to establish communication between the body (now acting as an electronic device) and another electronic device external to that body. This is not a replacement, but an enhancement, bringing novel capacities to the individual. It is thrilling, exciting for many, but horrifying for others.

Borrowing from the delineations of linguist Norman Fairclough, biotechnology might be said to involve instruments, objects, practices, values, forms of consciousness and discourses, and is interconnected to family life, economics, religion, culture and politics – all of which are connected as a medium by which truth may be revealed in our striving to define reality. Any time that determining reality is at stake, people become polarized. What is “reality” when it comes to defining the human being?

Technology is challenging our notions of being human. Indeed; we are living in the midst of another biotechnology revolution, where humans and technology are beginning to merge at the bodily level. Given the transformative and rapidly evolving nature of this revolution, our socio-cultural reality is in flux. As technologies increasingly become more deeply a part of our lives and bodies, there’s a lot at stake in having to determine what is, and what it means to be, a human being.

Q. What kind of concerns do you think deserve some full consideration and exploration?

A. First reaction: Eventually some kind of tracking, such as GPS, will be added to the capacity of these particular devices. But short of that, and trusting the assurances currently being made by the companies, many people may be concerned about any possible short- or long-term health risks from wearing such devices under the skin, for those who embed them and also for those who do not, but are in close proximity to those who do. How easily can they be removed, and must one “report” removal to an authority? What are the financial obligations now and into the future of wearing such a device?

Most likely the company’s culture will change as a result of its employees doing so, in which case what happens to the status and opportunity costs of those who choose to embed in contrast to those who do not?

Obviously, the question of privacy looms large. What rights one will have to maintain privacy in terms of purchases made, doors opened and closed, personal location and movement, who one spends their time with, how one uses their time, etc.?

There will, of course, be some people anxious about whether “big brother” could become involved, with government interests leading to determination of its right to have access to data collected from these devices. In which case, the company’s policy and promises could be overrun.

Q. Are any of the fears overblown?

A. This particular technology is a small part of a larger trend toward the use of bodily-embedded devices. What was in the 1950s a hand-held external pacemaker is now a generator inside the body, its wires connected directly to the heart – scary once, now the norm. With increased use, and time, fears of novel technologies will give way, and then the next scary technology will be looming.

To my thinking, fear is an expected and natural response to anything that poses a potential threat to one’s integrity. In this case, there is the sense that such implants could disrupt the wholeness of our being. Fear is appropriate when one perceives their body to be vulnerable to intrusion. And there is good reason for that.

Q. New technology almost always prompts initial concerns, but often transitions to acceptance and then ubiquity. Will that be the case with implanted chips?

A. Of course it will. We shifted from wall-mounted, hand-cranked telephones to desktop telephones with rotary dials, to the hand-held cellphones most of us now carry close to our bodies. My undergraduate engineering students have readily admitted that they can’t function without their cellphones, that they need to have them close by; without them, they feel insecure and dysfunctional.

To the matter of implanted chips (especially ones that could function like an embedded smartphone), they say, “Bring ’em on!”

Editor’s note: This story has been edited from its original posting to remove an inaccuracy.

Media Contact

Article Information

July 28, 2017

/content/cool-or-creepy-human-implanted-microchips-are-here