This month, University of Virginia developmental psychologist Tish Jennings traveled to India to share her latest research on mindfulness and teacher stress with the Dalai Lama. In itself, the opportunity is an honor and an accomplishment. For Jennings, it’s also a moment nearly 15 years in the making.

In many ways, the story begins in 2000, when the 14th Dalia Lama, the former Tenzin Gyatso, held a meeting with experts and researchers on the topic of destructive emotions. Out of that meeting, a question emerged: Could helping teachers manage their own stress improve classroom environments, and, in turn, student learning? The question became a research project called “Cultivating Emotional Balance,” which aimed to reduce stress in teachers through mindfulness training.

Meanwhile, as a Ph.D. student studying developmental psychology, Jennings took a listserv management job with the Mind & Life Institute, a nonprofit organization co-founded by the Dalai Lama that works to advance the field of contemplative science. Jennings caught wind of the Cultivating Emotional Balance project and was immediately intrigued. The project’s leaders had chosen to focus their research on teachers, largely on the assumption that happier teachers probably teach better, which could lead to better student learning outcomes.

As a former teacher and long-time mindfulness practitioner, Jennings recognized the assumption. She wanted to test it. So, after graduation, she joined the team – and began a career that would eventually land her in India, presenting her research to the Dalai Lama himself.

The Dalai Lama & Mindfulness

Since before he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989, the Dalai Lama has made education a central component of his teachings. In particular, he has been a leading advocate for social-emotional learning – or as he often describes it, educating both the mind and the heart. In a 2017 op-ed in the Los Angeles Times, he wrote: “My wish is that, one day, formal education will pay attention to the education of the heart, teaching love, compassion, justice, forgiveness, mindfulness, tolerance and peace.”

Mindfulness itself is one tool in the social-emotional learning toolkit. With origins in Eastern spiritual practices, today’s Westernized secular form of mindfulness is both a type of meditation and a mindset. In essence, it’s the learned ability to experience the present moment with openness and curiosity and without judgment. Evidence has shown that practicing mindfulness can improve emotional regulation and reduce stress.

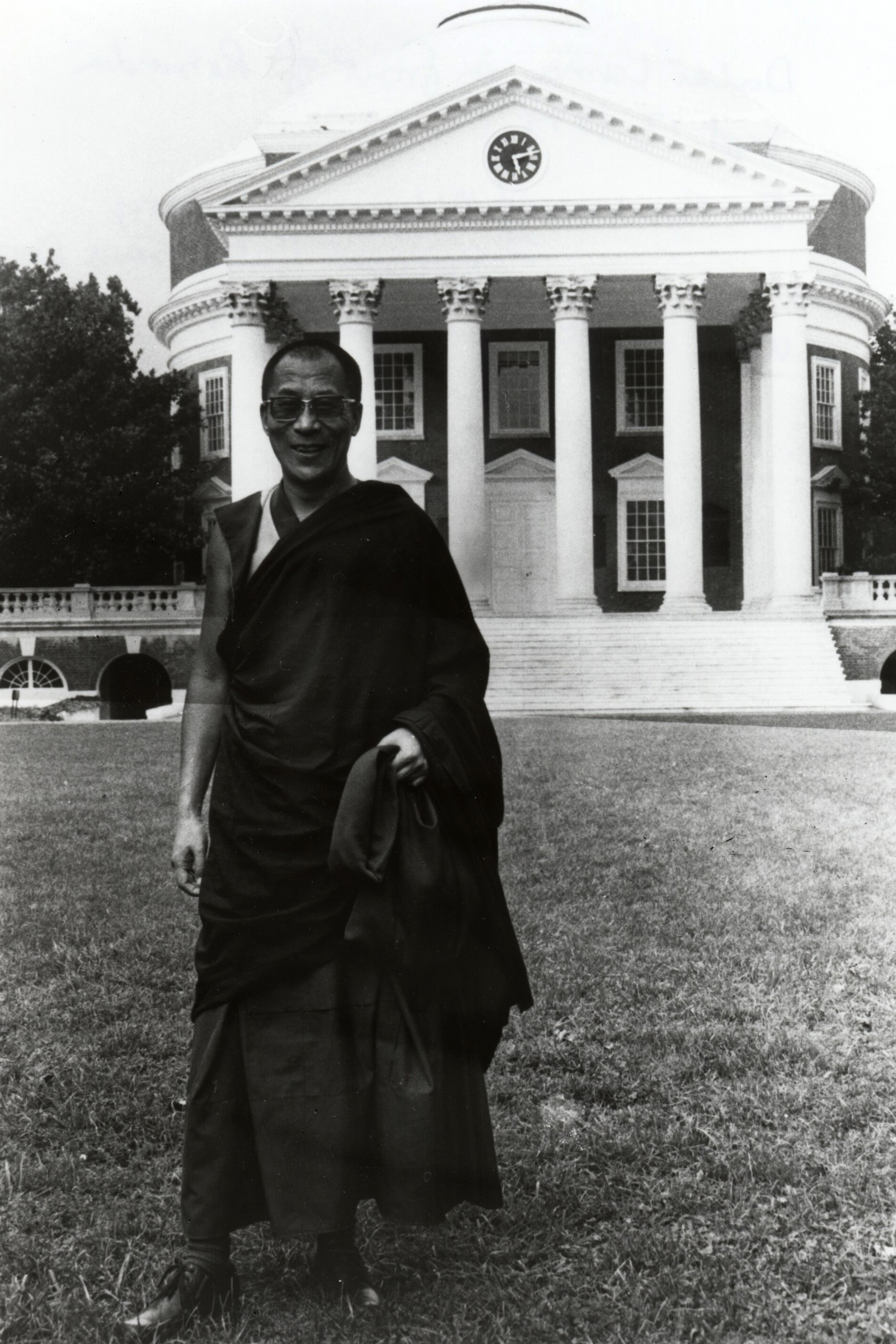

The Dalai Lama during a visit to Grounds in 1979. (Image courtesy Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library)

“It’s no longer a fringe thing,” she said.

While mindfulness has many applications, Jennings’ work has focused primarily on teachers. As a former classroom teacher, she knows just how stressful that environment can be. Imagine being confined to a room, charged with controlling a classroom full of young students – each with his or her own set of emotional, behavioral and cognitive challenges – while under constant pressure to improve test scores, all within a school day.

Even in the best scenarios, Jennings said, a teacher’s attention is pulled in many directions at once as she attends to all of these competing needs, all while keeping track of the content she is teaching. She may not take time to check in and monitor how she is feeling. The body’s physical stress response can arise without her even noticing, and suddenly, she’s feeling frustrated and more likely to overreact to student disruptions.

“When you’re in the heat of that angry moment, your mind is telling you that you have all the right in the world to be angry at that person, and you don’t see what you’re looking at clearly,” Jennings explained. “It distorts your perception.”

In a learning environment, stress management matters. “When your stress response is triggered, whether you’re a student or a teacher, the priority is not learning,” Jennings said. “The part of your brain – the prefrontal cortex – that you need to focus your attention on learning just kind of goes offline.”

Practicing mindfulness gives you the skills to see a situation more clearly and respond thoughtfully, rather than automatically reacting. For teachers, whose jobs rely on connecting with their students, this can make or break a career.

CARE for Teachers

Back at the Cultivating Emotional Balance project in 2004, Jennings received a Varela Award grant from the Mind & Life Institute to study the training’s effects. Jennings and her colleagues planned a pilot program to test whether or not mindfulness practices for teachers would translate to real differences in the classroom.

In order to do that, they needed a classroom measurement tool. They turned to the Classroom Assessment Scoring System, or CLASS, an observational instrument developed by now-Curry School Dean Robert Pianta to assess classroom quality in classrooms from pre-kindergarten through high school.

“That’s when I first became familiar with Pianta’s work and the Curry School,” Jennings said.

Ultimately, Jennings’ pilot project, as well as a follow-up study, did not find the impacts on classroom interactions for which she had hoped. But instead of giving up, she consulted with Paul Ekman, one of the leaders of the original Cultivating Emotional Balance project. Together, they realized one important puzzle piece was missing from their training: classrooms.

“When you reduce stress, it’s not necessarily going to result in someone behaving differently,” Jennings said, “unless you teach them how to manage the stress of that particular context.”

In other words, in order to help teachers improve their classrooms, you have to show them how to apply mindfulness concepts in the classroom.

Jennings moved to the nonprofit Garrison Institute, where she put that idea into action by co-founding a program called Cultivating Awareness and Resilience in Education, or CARE for Teachers. CARE for Teachers is a professional development program for teachers that combines mindful awareness and compassion practices with emotional skills instruction – specifically addressing the challenges and demands teachers face in the classroom.

“We took the mindfulness and the emotional skills training that were a part of [Cultivating Emotional Balance], but then we added some elements that connected to their understanding of what triggers their own stress in the classroom,” Jennings said. “We started realizing that, with training, teachers can manage that stress better.”

Since joining the Curry faculty in 2014, Jennings has continued to expand, study and improve the CARE program. CARE for Teachers offers an annual five-day summer retreat, or four daylong sessions spread out through a semester. Teachers practice role-playing stressful scenarios, learn to identify their personal triggers and practice techniques to manage stress.

Through CARE, Jennings and her team have trained countless teachers in how to maintain a supportive learning environment. Jennings herself has led training sessions in Charlottesville and throughout Virginia, and she’s also conducted numerous studies examining the program’s effects.

“I think what we’ve learned over this last decade or so is that, to promote learning, we really have to pay attention to the social-emotional environment – and a big part of that is the teacher’s own well-being,” Jennings said. “The CARE program is designed to help teachers understand that, practice it, and apply it to their daily teaching.“

Francien Vigour, a fifth-grade math teacher at Walker Upper Elementary School in Charlottesville, said the five-day training transformed her ability to handle stressful situations in the classroom. Small changes to her routine, like setting intentions on her morning commute, translate to big changes in the classroom.

“I learned to take care of myself first,” she said. “This year has been really difficult, and the reason I’m making it is because of CARE.”

A Dialogue with the Dalai Lama

Earlier this month, Jennings presented her research at the annual Mind & Life Dialogue, held at the Dalai Lama’s personal residence in Dharamsala, India. This year’s theme, “Reimagining Human Flourishing,” aimed to “focus on education, in light of His Holiness’ longstanding priority and deep commitment to secular ethics education initiatives.”

The dialogue lasted five days, and included both faculty presentations and discussions. Jennings was one of 17 professors selected to present their research on social-emotional learning.

Jennings presented some of her latest findings – and this time, the effects are clear. In results from a large randomized control trial, teachers who had participated in CARE reported direct positive effects on their psychological distress, stress associated with time urgency, mindfulness and emotional regulation, as compared to a control group. In addition, classroom interactions of teachers trained in CARE were independently observed to be significantly more emotionally supportive and productive.

“We collected teacher reports on over 5,000 students, and we found significant improvements in engagement among students who were in CARE classrooms compared to others,” Jennings said.

In addition, students initially low on social skills improved in reading competence.

“That, to me, is really exciting,” Jennings said. “Because for kids who don’t have the support at home like they need, it could make a big difference.”

Mainly, Jennings appreciated the opportunity to highlight her research and raise awareness about teacher stress and the positive effects of programs like CARE for Teachers. “The more positive attention that comes to these concerns, the more people get on board, and the more policymakers get it on their radar,” she said.

But personally, the trip holds even more significance. Beginning with the creation of the Creating Emotional Balance project, the Dalai Lama’s advocacy for the value of peaceful, happy classrooms has been a connecting thread throughout Jennings’ career. From her work with that project, to the professional network she built through the Mind & Life Institute, to the development of CARE – Jennings said his influence has been critical in shaping not only her field of research, but also the trajectory of her own career.

Sharing her research with the Dalai Lama himself represented a full-circle moment: an opportunity to discuss her life’s work with the person who, in many ways, started it all.

“How often do you get invited to do something like that?” Jennings asked. “It’s a once-in-a-lifetime chance.”

Media Contact

Article Information

March 21, 2018

/content/dialogue-dalai-lama-15-year-journey-mindfulness-and-education