When third-year University of Virginia student Lara Jabbour, doing research in neurology early this semester, encountered a patient unable to speak and in tears because of his frustration, an English course she was taking gave her an idea to help him communicate without words.

“In the midst of the Emergency Department, neurology ward, I was a tutor – exercising the very tools and techniques learned in ENPG 3559 [‘Tutoring Writing Across Cultures’],” she wrote to her classmates in their online discussion group. “I was able to approach the problem in a unique manner, allow the tutee to control the discourse, express empathy, and simply listen to the tutee.”

She knew he was there for a follow-up after having had a stroke recently; he seemed to know what he wanted to say, but couldn’t find the words. Along with exercising patience, Jabbour used visual images of everyday items to help him communicate.

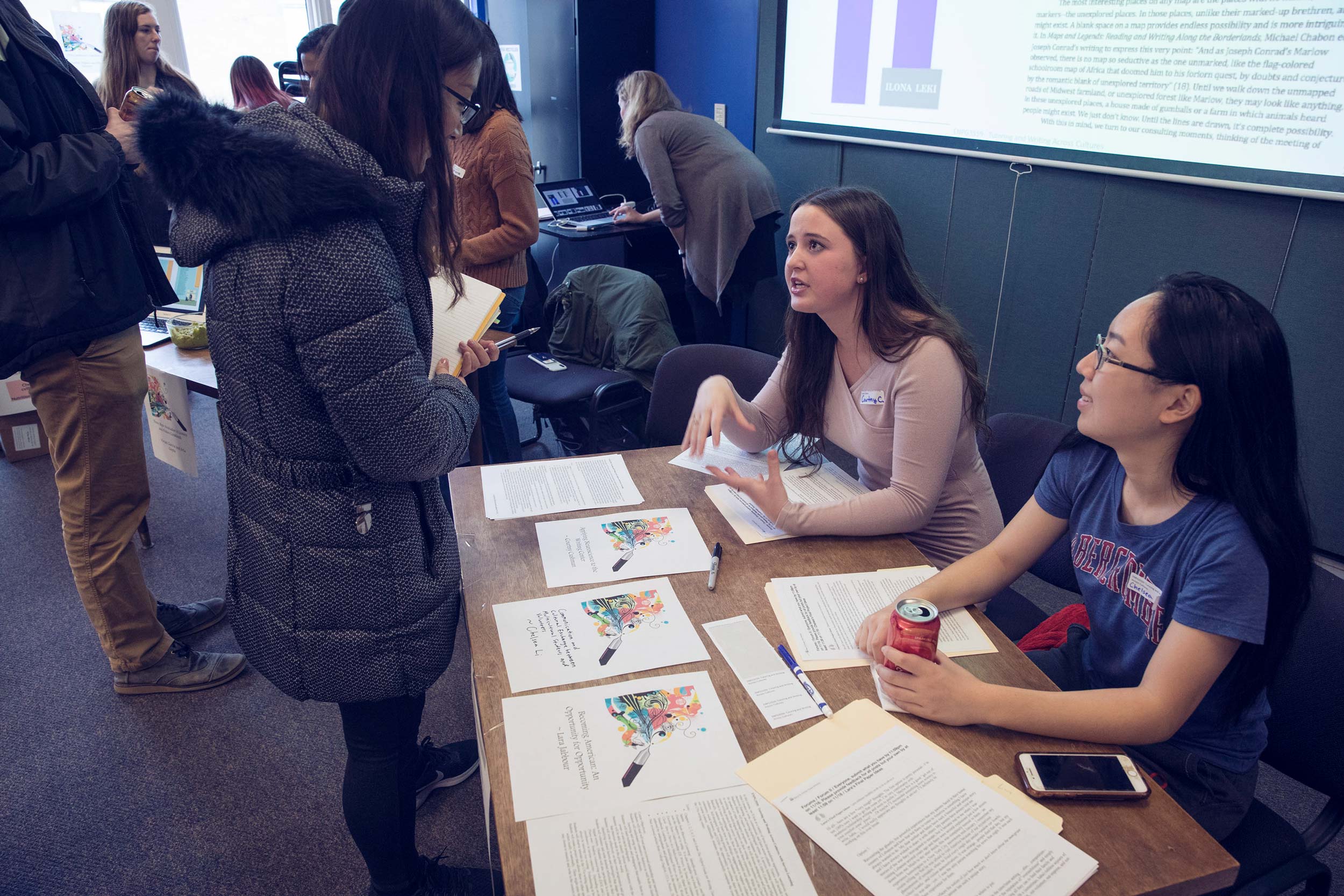

Kate Kostelnik, left, who teaches in the Academic and Professional Writing Program, brought students Courtny Cushman, Chelsea Li and Lara Jabbour to a showcase on community engagement and writing.

The course, “Tutoring Writing Across Cultures” – new this semester – may be dedicated to teaching students how to work with immigrants and international students, but just as important, it opens the door to the benefits of empathy and listening to others, whether they are peers or other people being tutored in writing English – or in Jabbour’s case, a patient. (She changed some details to protect the patient’s privacy.)

Offered through the English department’s Academic and Professional Writing Program, “Tutoring Writing Across Cultures” goes deeper than teaching pedagogy. It encourages students to understand the people whom they are tutoring and take into account their native writing styles. Taught by Kate Kostelnik, an assistant professor of English, the writing seminar incorporates service learning, in partnership with Madison House, the independent, nonprofit volunteer center for UVA students.

Required to volunteer in one of two Madison House programs, students put what they are learning into practice in either the English for Speakers of Other Languages program or in Latinx and Migrant Aid.

They also hone their own writing, research and communication skills. Kostelnik said that “the students have gotten really good at listening to each other and asking clarifying questions. They are all strong writers, but are more willing to listen to their classmates and to be receptive to feedback.”

She stressed that writing in these classes is not a solitary pursuit. The students improve through sharing drafts.

“This is collaborative learning,” Kostelnik said.

One of the most surprising things students said they’ve learned is treating differently what seem like mistakes that immigrants and international students might make in English – to consider that they might be using not only ingrained grammar rules from their native languages, but also other styles and techniques that could seem wrong in English.

“The way most people know their own language and grammar is whether it ‘sounds right,’ but English speakers of other languages don’t necessarily have that sense of English,” Kostelnik said.

Kostelnik “found that students were fascinated by the idea of contrastive rhetorics – that some writers, from specific cultures, structure their writing differently. While you can’t overgeneralize and make assumptions, it helps, when tutoring and teaching, to see that some students aren’t as direct in their writing as we are in American academic English,” she said. “It’s also critical to be clear that one rhetoric isn’t better than another.”

Kostelnik’s course is one of two writing courses that include community service as an integral element and require students to volunteer with related Madison House programs. The other one, assistant professor Kate Stephenson’s course, “Writing About Community Engagement,” focused on food insecurity and poverty.

In that course, students volunteered with Madison House community partners The Haven, a day shelter for the homeless and disadvantaged members of the Charlottesville community, and Loaves and Fishes, a local nonprofit organization that distributes food donated from area churches and other groups to families in need.

These two English courses, Kostelnik’s and Stephenson’s, hosted a Community Engagement Writing Showcase on service learning and writing last week, where students shared what they had learned in their research and volunteer work.

In a stellar example of professors learning from their students, Kostelnik said she was inspired to create her course by a former student, Chris Allen.

Allen, who took another of Kostelnik’s writing courses last year, wrote in an assignment about how volunteering with the ESOL program influenced his own learning of Chinese. Moving around a lot growing up, Allen had lived in China for three years when younger. At UVA, he chose the ESOL program to continue interacting with an international community. He tutored a middle-aged Chinese woman, and after their sessions, he would practice speaking Chinese with her.

Now head program director for Madison House’s English for Speakers of Other Languages program, Allen spoke to Kostelnik’s current students at the beginning of the semester and was responsible for placing some them with one of the seven local ESOL community partners.

“You build relationships with the people you tutor,” he said he told Kostelnik’s students. He advised them to be patient and remember that non-native English speakers would likely be translating between languages in their heads, a more involved thought process. He said it meant a lot to him to share what he had learned.

“Our students are so amazing!” said Kostelnik. “They’re putting their talents and energy to work in the community,” she said. They come from a range of disciplines – leadership and public policy, social and political thought, and computer science, as well as English.

“I want students to learn how to help people focus and develop their ideas into writing,” she said. “This training is useful for any career.”

Kostelnik noted, “They learn responsible ways of teaching that include being culturally sensitive.”

Fourth-year student Adeline Sandridge echoed that, saying she appreciated learning “great skills that can be applied in different contexts – in tutoring, at the Writing Center, and in life.”

A student in the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy, she said although Batten’s rigorous academic program includes lots of writing, she sees a need for the school to have its own dedicated writing center. For her final project, she’s proposing and designing such a center as a supportive environment where peers help each other.

Sandridge, who took her first-year required writing course with Kostelnik, said that class “changed her perspective on writing, on how the writing process works and how writing is an art that can be improved.”

She thought this course would be “an awesome opportunity” to enhance her writing skills in the two different settings: an academic class concentrating on the pedagogy of teaching international students, and the extracurricular experience of tutoring high school students, some of whom came from Latin American countries. Also minoring in Spanish, she felt her fluency in that language would be helpful – and it has been, as she has worked with the parents of these students as well.

“As I’ve gotten to know them, I feel invested and want them to do well,” Sandridge said. She has appreciated discussing with her peers what’s best for the ESOL students, from nuts and bolts such as what to do if someone asks for an answer to putting their work in a larger context.

Like Sandridge, Jabbour has tried to understand the background of those she’s tutoring. She is helping the instructor of an ESOL class for adults in Charlottesville who range in age from their 20s to 60s. Her final project, “Becoming American: An Opportunity for Opportunity,” includes the experiences of her parents, who emigrated from Lebanon to the U.S. about 20 years ago, and compares what resources they had for learning to speak and write English with what’s available these days.

“Everyone’s story is unique. Connecting [with the immigrants in the class] is really important,” she said.

That proved true in Chelsea Li’s volunteering experiences, too.

Li, a third-year student majoring in English and human biology, was trying to help a woman from the Middle East who wanted to improve her writing. When she got to know the woman, a recent immigrant, Li found out she had taken a writing class elsewhere and the instructor was more critical than helpful. When Li shared with her the basic five-paragraph structure of an essay that young Americans learn, it helped this woman immensely.

“It was a direct application in the one-on-one tutoring of what we learned in class,” she said, “that the person’s culture informs their writing even as they’re learning in English. It’s more humanistic to figure out what’s underlying the way they write. I wanted to help her feel empowered to progress in her writing.”

The Academic and Professional Writing Program also offers other classes that include at least one project involving community service. In addition, the program is reaching out to professors in other disciplines who are interested in incorporating writing and service learning into their courses, with Madison House assisting through its volunteer structure.

Media Contact

Article Information

December 6, 2018

/content/volunteering-helps-students-breathe-life-their-writing