Tobacco is not a simple crop. It is commodity fraught with health, economic and political implications. These last are the focus of Sarah Milov’s new book.

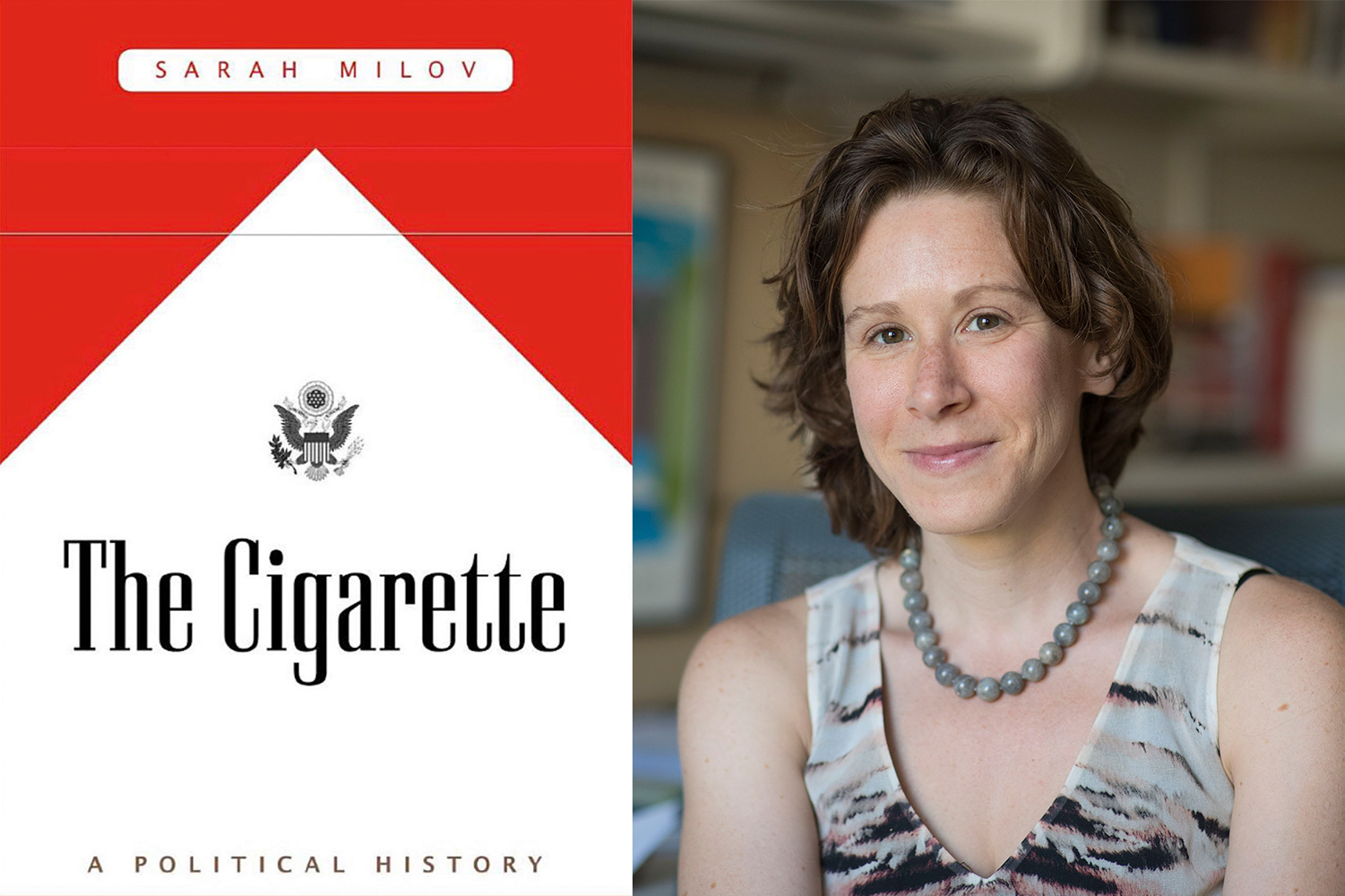

Milov, an assistant professor in the University of Virginia’s Corcoran Department of History, has expanded her Ph.D. thesis into “The Cigarette: A Political History,” a look at the politics, both national and local, that swirled around cigarettes in the mid- and late 20th century, and the non-smoker’s movement that helped rob cigarette smoking of its cachet.

The book has earned strong reviews and notes in The New Republic, Nature and The New York Times.

“For most of the 20th century, tobacco and cigarettes were a product of the federal government,” Milov said. “The government’s investment was in producers of tobacco inside the United States and also consuming tobacco outside the United States. In the post-war decades, U.S. tobacco was shipped overseas and put in cigarettes produced by foreign tobacco monopolies. In a way, it was surplus disposal for American farmers and supported the treasuries of foreign countries as they were seeking to rebuild their economies in the post-war period.”

She explores the creation of the farm support system in the 1930s as a way of coping with the Depression.

“During the New Deal, the system was put into place because the government wanted to protect the livelihoods of a privileged set of Americans,” Milov said. “There was an understanding of the economy of rural places as integrally related to the economy of urban places, and so in the midst of a depression, you had to revive agriculture if you didn’t want to throw more people out of factories.”

But, Milov noted, to revive agriculture, the government had to tell farmers to stop producing so much, a natural reaction when a commodity’s price goes down. The government did this through creating tobacco allotments.

“I went into the project thinking the story would be a lot more elite-driven, that the story would be that the surgeon general’s report would be the thing that mattered the most. I did not realize before doing the research how much grassroots activism this took.”

- Sarah Milov

“The government steps in and basically locks in historical tobacco production.” Milov said. “The farmers were assigned acres to produce based on what they produced in 1933, so this ends up locking in historical production patterns, which ultimately is seen as quite unfair by people who participate in the program – not to mention people in Congress who, by the 1980s, are taking on a more bipartisan skepticism toward agriculture programs like this generally.”

After World War II, U.S. tobacco was sent overseas as part of the Marshall Plan, which was a mixed blessing for some recipient countries. Some governments, including Greece and Turkey. wanted the U.S. to rebuild their domestic tobacco farming, while others were glad to have the tobacco for the local cigarette industry, since these governments levied a tax on cigarettes when they were sold.

And while excess U.S. tobacco found an outlet in foreign markets, importation of foreign tobaccos began to damage the domestic market for farmers.

“There is this provision in trade law that says you can import commodities, such as tobacco, as long as it wasn’t the same grade and wasn’t directly competing with the stuff grown in the U.S.,” Milov said. “So the companies begin to import what was called scrap tobacco, and they end up with a larger and larger portion of American cigarettes filled with foreign scrap, which basically unravels the basis of the domestic program, because less and less domestic tobacco is being used. It is being drowned by the so-called inferior scrap imports.”

Milov said the tobacco companies hurt the domestic tobacco producers.

“Now tobacco farmers farm on contract, and if you farm for R.J. Reynolds or Altria they can just dictate the price to you and say they are not coming back next year,” Milov said. “It is not a particularly happy ending.”

And while the one part of the federal government was trying to support U.S. tobacco farmers, another part was sounding the warning claxon.

“Lung cancer had been an exceedingly rare disease prior to the 1940s,” Milov said. “It was something that a doctor would never really see in his lifetime. But now you start to get more instances of it showing up, and by 1964, the surgeon general had come out with a report convened by a panel of experts who have reviewed all the scientific literature, and that is the first government statement you get that smoking causes cancer.”

And while smoking rates dipped after the surgeon general report, they rebounded shortly afterward as people found it difficult to stop addictive behavior. And then a non-smokers’ rights grassroots movement started up.

“What I argue is that the important decline in smoking is not just [due to] knowledge, because tobacco is an addictive thing. You want to do it,” Milov said. “What made people stop smoking [was] having fewer and fewer places to do it. The goal of the non-smokers’ rights movement was, in their words, to make smoking socially unacceptable, by cordoning off smaller and smaller places where people can smoke.”

Citizens, not government, drove the anti-smoking movement, she said.

“The activists in the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s never found the federal government to be their friend, and found a greater ability to curtail smoking by working at the very local level or getting workplaces to implement smoking bans,” Milov said, “driving smokers out of common spaces they had shared before, and driving them out of business spaces, forcing them to leave to go smoke. Workplaces that adopt smoking bans or smoking restrictions in the 1980s find that in many instances, they help people quit. So it is a movement that builds on itself. By making fewer places for people to smoke, they end up creating more non-smokers.”

For a movement with such wide-reaching impact, the anti-tobacco activists had modest beginnings.

“One of the first non-smokers’ rights groups starts in a woman’s living room as she and her girlfriends decided that their first anti-tobacco action would be to remove the ash trays from their houses,” Milov said. “And they have to talk about it because they know they are going to get on the nerves of, and disappoint, people who are visiting them.

“The second thing they decide to do is launch a letter-writing campaign to local doctors asking them to consider banning smoking in their offices.”

Milov did not expect this grassroots nature of the anti-tobacco movement.

“I was surprised to learn more about the granular, homespun, low-tech details of the early years of this movement that ultimately became the dominant wave as we think about space, who shares space, and about who gets to determine space today,” she said.

And with this granularity, the anti-tobacco movement worked with state and local governments on anti-smoking laws. Milov paints a picture of tobacco growers supported by the federal government and a grassroots movement that worked through local and state governments.

“I went into the project thinking the story would be a lot more elite-driven, that the story would be that the surgeon general’s report would be the thing that mattered the most,” Milov said. “I did not realize before doing the research how much grassroots activism this took and also the power of activism – not through the federal government; that’s not where they succeeded. They succeeded through the local government, and local governments continue to be where smoking rules are made, where indoor smoking regulations are created.”

While the anti-smoking movement gained momentum and the tobacco industry was driving down the price of tobacco, federal tobacco supports continued.

“The tobacco supports lasted 70 years,” Milov said. “They outlasted several other kinds of commodity support and were in place for five decades after the surgeon general issued his report. The government’s commitment to support tobacco farmers was pretty significant.

The civil rights movement also inspired anti-tobacco activists.

“The non-smokers’ rights movement ends up trying to use a lot of that rhetoric,” Milov said. “They say non-smokers are an oppressed group, that their rights are being trampled on by smokers because they have a right to breathe freely. Then – and this shows the flexibility of this language – they also say they’re not just a poor oppressed minority, they are a poor oppressed majority, just like the ‘silent majority.’”

“One of the first non-smokers’ rights groups starts in a woman’s living room as she and her girlfriends decided that their first anti-tobacco action would be to remove the ash trays from their houses.”

- Sarah Milov

Former President Richard M. Nixon, a politician closely associated with the concept of the “silent majority,” also created the Environmental Protection Agency, which influenced the anti-smoking movement.

“Another turning point is the advent of air quality standards that are enforced and devised by the EPA,” Milov said. “The EPA does not regulate indoor air quality, but the standards give non-smokers’ rights activists hard data to appeal to when they say secondhand smoke is harmful because it releases these chemical constituents which, if they were coming from a smokestack, would be the subject of regulation.”

Anti-smokers appealed to employers and business strategists to ban workplace smoking, arguing that smokers were essentially bad workers; they took too many breaks, they destroyed equipment, they were sick more, they cost too much to insure and banning smoking at work improves efficiency.

“The goal was to make smoking socially unacceptable, but in order to achieve that goal, they had to make smokers socially unacceptable,” Milov said. “That ended up falling hard on people who tended to be working-class or unemployed. There is a self-righteousness of non-smokers that can be really unsympathetic to the reality of addiction. They were called annoying, but they were annoyed and sickened themselves. In the fray of the moment, everyone is calling each other annoying.”

Milov says the story she tells is not a happy one, with a lot of people on the losing end.

“I think small-scale tobacco farmers got a raw deal in the way this all went down,” Milov said. “Small-scale tobacco farmers needed more help from government than they got, and actually it would be better, in my opinion, from a public health perspective, for a return to the tobacco program, because it would take money away from the companies and it would raise the price of tobacco, which is a good thing if you care about people not smoking.

“I think tobacco farmers needed help. I think smokers need help. If they want to quit, that should be more available than it is, particularly for people who don’t have health insurance.

“But insofar as non-smokers’ rights activists created a more non-smoking world, I am glad I live in that world.”

Media Contact

Article Information

October 10, 2019

/content/cigarettes-weave-complex-path-through-past-century-historian-finds