The rooms bounding the University of Virginia’s iconic Lawn have housed any number of distinguished students who went on to do great things. Journalist Katie Couric lived in 26 East Lawn. Basketball legend Ralph Sampson lived in 6 East Lawn. Daniel French Slaughter Jr., a four-term United States Congressman, Purple Heart Army veteran and former rector of UVA’s Board of Visitors, lived in 9 West Lawn.

Here is another interesting fact about the residential history of the storied Lawn: Since the late 1970s, 37 West Lawn has been reserved for the chair of UVA’s Honor Committee.

Lawn Room Circa 1980 vs Lawn Room Circa 2016

Some digging reveals several 37 West Lawn residents who went on to do extraordinary things. Of the four featured here, one served a 16-year tenure as the U.S. Surgeon General. Another went on to become a distinguished foreign service officer and the U.S. ambassador to Indonesia. A third blazed a trail in Washington, D.C. as the founding publisher of The Root, an African-American focused news outlet launched in 2008 by Donald Graham, a former publisher of the Washington Post, and well-known Harvard scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. The current resident will graduate in May and take a job in her home state of Florida, where she will work at the world’s largest utility company.

Their stories, arching from 1891 to 2019, show the outsized impact UVA students have had on the United States. They also offer a good reflection of the University’s evolution from its founding to today, as UVA President Jim Ryan inspires the UVA community “to be both great and good in all we do” in its third century.

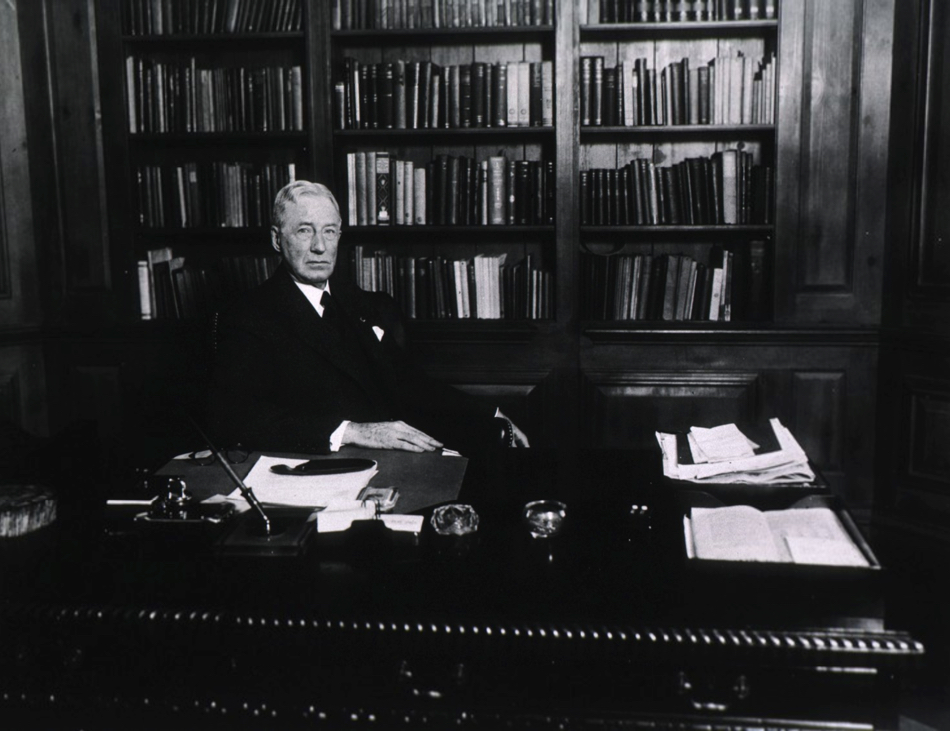

Our story begins in 1891, when Hugh S. Cumming Sr. enrolled at UVA, moved into 37 West Lawn and earned his medical degree. According to records kept by the Department of Health and Human Services, he obtained a commission as an assistant surgeon in the Marine Hospital Service in 1894, at age 25. He would remain in public service for the remainder of his professional career.

A large part of Cumming’s early work concerned immigration and quarantine policy, meant to limit the spread of contagious diseases in the United States. Cumming served in the Navy during World War I and was later sent to Europe, where he studied sanitary conditions in an effort to prevent the spread of disease by American troops returning home.

His work in public health continued after his appointment as surgeon general of the Public Health Service in 1920. Among other efforts, he launched a new plan to examine immigrants at their countries of origin before they made the long journey to the United States, in order to reduce the number turned away due to illness. He also expanded the U.S. Public Health Service beyond physicians, to include pharmacists, sanitary engineers and dentists.

With Cumming’s good work, however, came a regrettable legacy. The “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male” was launched in 1932 during his tenure as surgeon general. Continued by his successors, the program studied the progression of venereal disease in African-American men, while offering them no treatment. The now-infamous study was halted in 1972 after a panel found it to be “ethically unjustified," and President Bill Clinton in 1997 formally apologized to the victims on behalf of the United States.

Like his father, Cumming Jr. pursued government work, though he set his sights on becoming a diplomat. To get his foot in the door, he took a job in the international department of a large bank, a position that took him to Europe and Singapore. Next, according to a Washington Post obituary, Cumming began his slow, steady ascent to ambassador to Indonesia with a series of high-level assignments dealing with international economic relations.

From 1947 to 1950, he served as counselor to the U.S. embassies in Sweden and Russia before Eisenhower nominated him to be ambassador to Indonesia in 1953, just a few years after the Dutch recognized Indonesia’s independence. Cumming returned to Washington after his four-year stint in Jakarta and was appointed assistant secretary of state for intelligence and research until 1961.

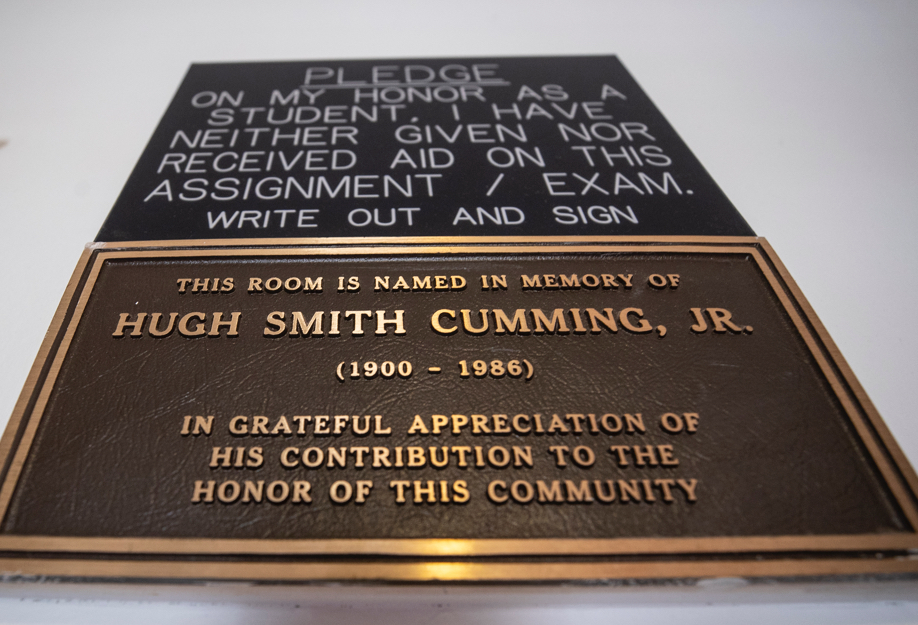

His time living in the Academical Village was apparently still on his mind all those years later. In the late 1970s, Cumming Jr. created an endowment to designate 37 West Lawn as the permanent home for chairs of UVA’s student-run Honor Committee, Gilliam said.

Later, Cumming established the Hugh S. and Winifred B. Cumming Memorial Chair in International Affairs at UVA. The first person to hold that title was the late David Newsom, a high-ranking diplomat at the center of the Iran hostage crisis of 1980.

Cumming Jr. died of cancer in 1986. He donated his families’ papers to UVA’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

Founder, BLUEBUTTERFLY, 2018-Present

Two years after Cumming Jr.’s death, a young woman named Donna Byrd arrived on Grounds as a first-year student.

An unsettling exchange that first year would put her on her own path to 37 West Lawn and beyond, a path that led her to her formative work today.

Byrd had gone to an Honor Committee education seminar in her dorm, and the discussion turned to the disproportionate number of African-American students being asked to leave UVA because of honor code violations. A white student stood up and made a pronouncement that caught Byrd off-guard. “‘Of course, black people cheat. They have lower test scores and they are not going to make it through the University,’” Byrd recalled the student saying.

Suddenly, she felt everyone’s eyes turn to her, because she was one of the few African-Americans in the room.

“I just remember thinking to myself that if the Honor System was such a big part of the University, that I wanted to get involved and understand it from an internal perspective and understand if there were real problems that were going on from a structural standpoint,” Byrd said.

She joined the Honor Committee and served in several capacities before being elected chair of the body, whose charge is to uphold the honor code requiring that UVA students never lie, cheat or steal.

That conviction guided her work as Honor Committee chair. She spent a tremendous amount of time ensuring that her team was getting the evidence they needed for each case and treating each student who came through fairly.

“That was one of my top priorities, to make sure that the system was applied equitably and fairly to all students,” she said.

Byrd felt a sense of legacy living in 37 West Lawn.

“I knew that the people who had lived in the room before me had been Honor Committee chairs. I felt a great deal of responsibility to ensure that I led in a way that would be respected by those who had come before me,” she said.

Byrd graduated from UVA in 1992 with a degree in American government, and in 1996 earned her master’s degree in business from Duke University. She held a number of marketing and media positions early in her career, including at Proctor & Gamble and Coca-Cola. Eager to leap into the online world with the rise of the Internet in the late 1990s, Byrd served as the vice president of marketing for ezgov.com, an online resource for government-related information, CEO at Black America Web and co-founder of a planning and branding firm called Kickoff Marketing. Then a major career opportunity came knocking.

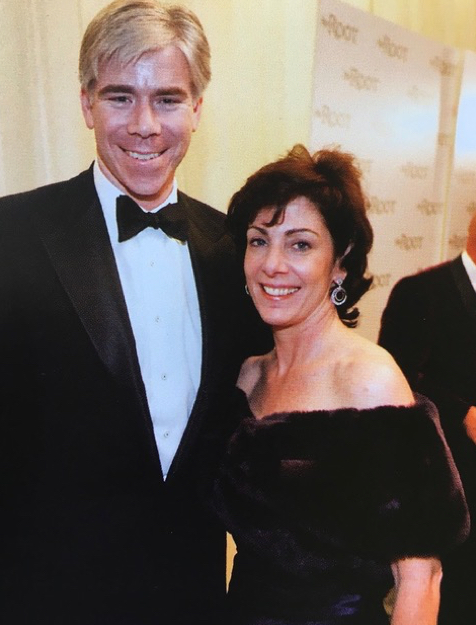

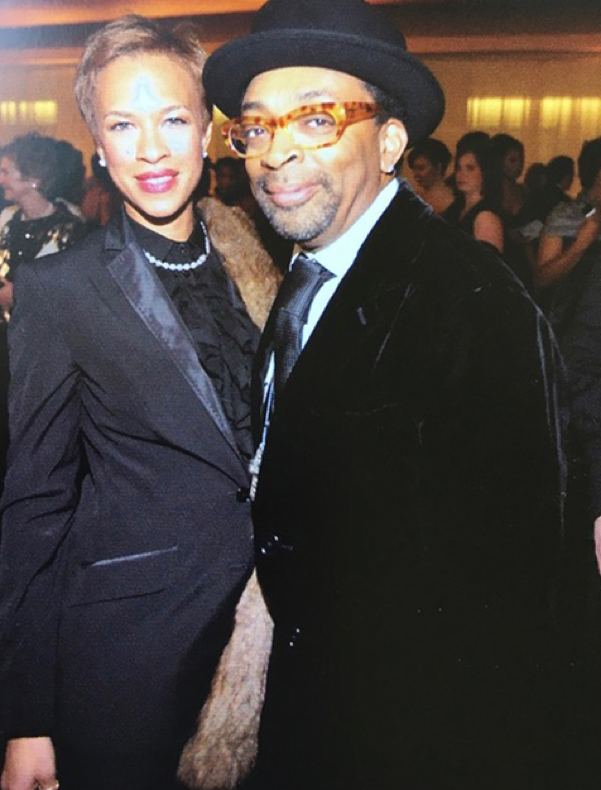

A Moment in Modern Journalistic History

In 2008, Donald Graham, the previous publisher of the Washington Post, and Henry Louis Gates Jr. of Harvard approached Byrd. They had a job offer: founding publisher of The Root, a new, cutting-edge online news publication that would be aimed squarely at African-Americans.

After a meeting at Washington Post headquarters, Byrd was “absolutely blown away” by the people she met. Graham and Gates were similarly wowed by Byrd’s vision for The Root. She wanted the publication to reflect the views of a new generation of African-Americans, people who had been brought up in integrated schools and communities and saw the world through a lens slightly different from their parents.

She was offered the job and launched The Root eight days before the “Super Tuesday” primary election, when a young presidential candidate named Barack Obama began to surge in the polls.

Eight months later, in November 2008, Obama was elected the first African-American president in U.S. history.

Byrd and her staff of five people were huddled in their office in Dupont Circle when the election was called in Obama’s favor late in the evening of Nov. 4. “We had a television on in the office and everyone was typing, trying to prepare their articles for the next day,” Byrd said. “I will never forget the moment they said Barack Obama would be the 44th president of the United States.

“There was incredible elation in the office and we could hear the taxicabs beeping their horns outside. People started screaming and yelling and cheering.”

The staff finished their work and that night The Root published several perspectives. One headline read, “In Our Lifetime.” Published at 12 a.m. Nov. 5, the byline belonged to Gates, who reflected on the historic nature of the time.

“…[W]e have never seen anything like this,” he wrote. “Nothing could have prepared any of us for the eruption (and, yes, that is the word) of spontaneous celebration that manifested itself in black homes, gathering places and the streets of our communities when Sen. Barack Obama was declared President-elect Obama.”

Another Root piece dubbed Obama the first “Internet President.”

“We felt like we were part of history, publishing the words and viewpoints of African-Americans at such a pivotal time,” Byrd said.

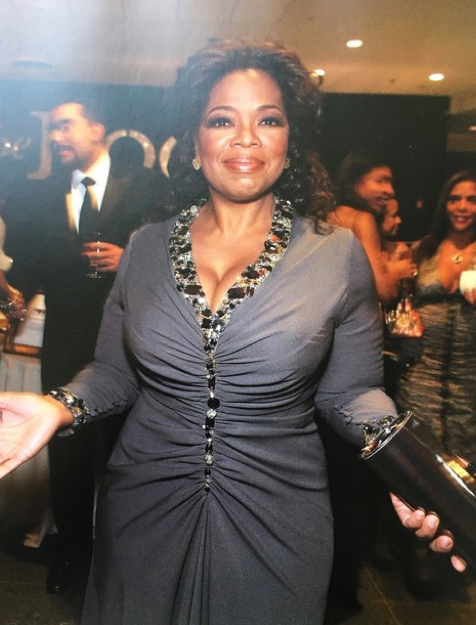

The Root became the go-to source for Fox News, CNN, MSNBC and other outlets, which put new emphasis on featuring African-American pundits. Byrd’s work garnered lots of attention; she was profiled in Cosmopolitan magazine in 2015 and asked to contribute to “Black Girls Rock,” a collection of essays with entries from Michelle Obama, Beyoncé, Angela Davis and Serena Williams. Byrd remained publisher of The Root until 2017.

Embracing Change

Because her Army family moved so frequently during her childhood, the entrepreneur learned to embrace change at an early age.

Rather than dread those moves, mother Diane made them a fun adventure for her children, decorating the house with pages out of magazines with photos of the Eiffel Tower and the Leaning Tower of Pisa after they were given orders to move to Germany. Byrd remembers her mother greeting her and her siblings at the door one day after school and telling her children to “run around the house and look where we are going next!”

That ability to accept and even embrace change has stayed with Byrd and accounts for her diverse career. “I ask myself, ‘Where can I go, what can I do next to be helpful?’”

She got that answer in 2015 when she lost four people close to her: two family members, her boyfriend and a close friend.

“During that period, I had an opportunity to see, up close and personal, the funeral industry, and I found it to be fragmented. I found people in the industry preying on individuals when they were grieving, and it made me angry,” she said. “I was in the middle of selling The Root [to Univision Communications] at that point, and I just made a mental note that one day, I was going to do something about it.”

Today she is. Byrd is launching a new company called “BLUEBUTTERFLY,” an online platform helping people avoid the anguish she suffered by simplifying funeral planning, reducing costs and making it easier for those grieving the loss of a loved one to create a supportive community.

She and her team are in the midst of a soft launch to work out all the bugs and hope to fully launch BLUEBUTTERFLY later this spring.

It’s a dramatic career shift, but to Byrd it feels like a calling.

“I am so excited to be in this space,” she said. “I get up every single morning excited about building something that I believe will help people in their time of need.”

Vice Chair for Education on the Honor Committee

In a twist, this year’s Honor Committee chair is not living in 37 West Lawn; the current chair, Ory Streeter, is a fourth-year medical school student who is married with a young child. That brought us to Julia Batts, vice chair for education for the Honor Committee. Streeter said it made sense for Batts to live on the Lawn because her position was so outward-facing. He also felt she would be a good ambassador for his stated goals of promoting honesty, integrity and generosity throughout the University.

Batts was a dorm representative for the Honor Committee in her first year. In that role, she was a familiar, friendly face to her dormmates and answered basic questions about what constituted an honor offense and how cases proceed through the honor system.

During her second and third years, as a support officer, Batts advised and investigated cases. That means she was, at times, either advising students who had been reported for an honor violation or investigating reported students.

“You’re the confidential resource to either the reported student or the reporter” of the honor violation, she said. Investigators are impartial fact-finders of the case. “They conduct any and all interviews that need to happen during the investigation,” she said.

Advisors work with reported students to inform them of the investigation process and their rights.

Batts said she will be taking some hard skills with her into her new job, skills learned during her time on UVA’s Honor Committee.

“One of the things it has definitely helped me with is public speaking and presentation skills,” which she said she will need at NextEra Energy. “Now, standing up in front of a group of strangers and talking about something that I care about and I’ve been working on no longer really fazes me.”

Perhaps more importantly, Batts said her tenure on the Honor Committee has taught her empathy. “It’s taught me to never judge someone immediately from the surface, because you never know what they’re going through deep down inside,” she said.

As Batts takes those lessons with her, 37 West Lawn will welcome yet another resident, and her evolution, like that of the University around it, will continue.