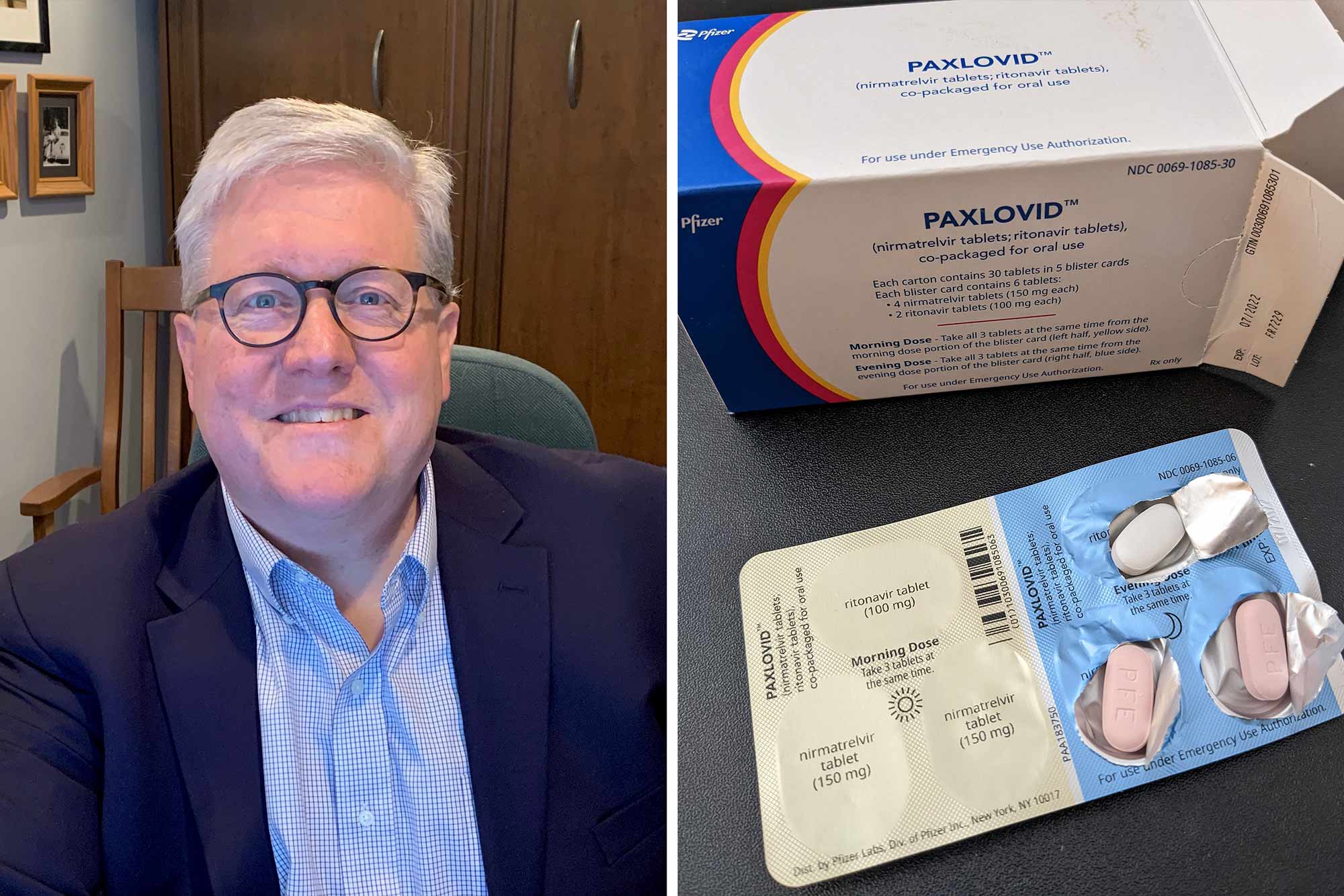

Sometimes it’s not just the information you know that’s important; it’s knowing what you want out of life. When the two dovetail, you get people like Dr. Jay Purdy, the University of Virginia graduate who was part of the team at Pfizer that developed the lifesaving drug Paxlovid.

Purdy’s decision to step away from the bedside and academia, and cross over to the pharmaceutical side, put him in a position to help many more patients.

“I think that’s why we all get up and go to work in the morning,” Purdy said from his office in Collegeville, Pennsylvania. “When we make advances, we can change lives by the tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of people at a time.”

Once the seriousness of COVID-19 became clear at the end of 2019 and into 2020, the race was on for a pill intervention. Doctors and epidemiologists knew then that potential vaccines would only be able to do so much, especially among populations reluctant or unable to take such precautions. In the absence of natural or heard immunity, treatment would be required.

Compared to the news of Pfizer’s successful vaccine partnership with BioNTech earlier in the crisis, Paxlovid, to which the FDA granted emergency authorization in December, is more quietly saving the lives of infected people at risk of serious complications. In trials, the drug demonstrated an 89% success rate in reducing hospitalization or death in patients at high risk.

Purdy, who received both his M.D. and doctorate in microbiology from UVA, explained to UVA Today how the miracle pill went from the research stage to the delivery of 10 million courses of the drug – and that’s just in the U.S. alone – in under two years.

He also detailed his own path to Pfizer’s c-suite, where he has been vice president of the Global Medical Affairs division and the therapeutic area lead over the development of anti-infectives since 2018.

Developing Paxlovid

“To develop a drug from start to finish takes years and years, and we knew just didn’t have that amount of time,” Purdy said.

But given the urgency, it helped that Pfizer’s labs had some experience with coronaviruses, a viral family that affects both birds and mammals, notoriously causing respiratory infections in humans.

COVID-19 is alternately known to scientists as SARS-COV-2, It’s a relative of SARS-COV-1, which clinicians fought from 2002 to 2004. Before SARS (short for “severe acute respiratory syndrome) burned out, Pfizer began trying to formulate a drug to defeat it.

The company later added to the research another coronavirus that appeared in 2012: MERS (“Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome”).

The efforts started with computer models to identify small molecules – organic compounds that can regulate bodily processes – as potential therapeutics. Tinier and relatively simpler compared to other biologics, including the agents in vaccines, small molecules are usually delivered in pill form for our guts to absorb and our bloodstreams to distribute.

“By the time SARS-COV-2 came around, we knew we had small molecules that seemed to target the appropriate molecule in coronaviruses,” Purdy said.

But because the previous crises had abated, the relevant labs had shut down. Pfizer wasn’t even close to having a candidate drug – unlike competitor Merck, which had a contender before the pandemic.

Purdy credited Pfizer’s leadership with supporting the development of both vaccines and antivirals in its all-out effort to fight COVID. His role in the fight has been to assemble team members and oversee the drug’s collaborative work within the Global Medical Affairs group, a project that has involved thousands of partners.

In 2020, Pfizer compounded about 600 variations before arriving at the formulation for its antiviral nirmatrelvir, a protease inhibitor. Proteases break down protein and are required for viral maturation and replication.

Along with an established drug, ritonavir, which keeps the antiviral from breaking down too quickly, the company created the combined product Paxlovid.

Patients take 30 of the pink-and-white pills over the course of five days. The drug is not a substitute for vaccination. And it is only recommended for use by patients with active infections who are at risk for serious complications.

Merck’s drug molnupiravir, developed in partnership with Ridgeback Biotherapeutics, proved less effective in clinical trials. That made Paxlovid the go-to product, although the FDA has authorized both for emergency use.

Pfizer’s large staff (the company has about 80,000 employees) and worldwide reach made it possible to start the rollout of Paxlovid in record time – weeks after the key trials.

“Just the production alone is remarkable, how fast we went from a drug that did work to a drug you can get in stores,” he said. “The acquisition of all the ingredients that go into making Paxlovid is difficult. There’s only a limited number of suppliers, and often times the ingredients are being used for other applications. You have to collect the components from around the globe.”

Purdy said while his colleagues at Pfizer deserve credit for the drug’s development, the real heroes are the sick people who participated in the trials.

“They didn’t know if the drug was going to work,” he said. “We didn’t have a full view of the safety profile of the drugs. Based on animal studies and healthy human studies, it appeared as if it was a safe drug, but until we got the data, we didn’t know for sure.”

Developing His Career

Before Purdy was a vice president at Pfizer, he was a UVA graduate – first in 1995 in microbiology, then in 1997 from the School of Medicine. He completed his residency at the University of Iowa and became a faculty member before moving on to the University of Chicago.

As an assistant professor there, he continued to teach and practice in internal medicine as an infectious disease expert. But something began to feel lacking, he said. He enjoyed his various duties, but direct patient care had become rote rather than the challenge that it had once been. And, “Training, seeing patients and doing research made it hard to see my family.”

Purdy was in the process of applying for research funding – Chicago maintains a coveted R1 university rating because of the high volume of studies it manages to get funded – when Tracy, his wife, asked the question that changed his trajectory – in the middle of an R01 application.

“If you get it, do you still want it?” she asked.

“A lot of the joy had left,” Purdy added. “That’s when I received a call from a headhunter.”

He joined the pharmaceutical company Wyeth in 2008 as an associate director of clinical research. He rose to director of clinical research, then senior director as Pfizer acquired the company, before finally making vice president.

Purdy has spent the majority of his pharmaceutical career working on anti-infectives, which included antibacterial development, vaccines and now antivirals. For a period, though, he also oversaw the vaccine Prevnar-13 for adults. The vaccine provides protection against pneumococcal bacteria – bacteria that can cause pneumonia and lead to other invasive diseases.

Though such breakthroughs are big, Purdy prefers to think smaller. As in less than the size of a strand of protein.

“My real love is small molecules,” he declared.

Seeing Paxlovid to the Next Stage

Now that Paxlovid is widely available, Purdy helps make sure it’s used correctly.

“I work at answering the questions of folks who are going to provide recommendations, physicians who have questions about safety, to make sure the proper and accurate data is available,” he said.

As the drug progresses beyond emergency-use status, he’ll be part of the team creating the extensive drug labeling, also subject to FDA approval.

Pfizer still has some questions to answer about Paxlovid. The most pressing involve the rebound some patients experience after initially feeling better. Is it a normal part of the recovery process? Or is there something different about the way COVID-19 rallies against this drug?

“We see it in patients who receive the drug and patients who don’t receive any antiviral,” Purdy said. “The viral load drops, and then pops up again down the road.”

While Pfizer first estimated about 2% of patients who take the drug experience some sort of “rebound,” a vague term that could indicate a variety of symptoms accompanied by a viral uptick, emerging evidence has opened a discussion about whether that percentage holds true in the current broader population.

Participants in Pfizer’s EPIC-HR study that led to emergency authorization suffered from the delta variant of COVID-19 and were unvaccinated. Researchers are currently investigating rebound in patients suffering from the omicron variant who have been vaccinated. While the ultimate usefulness of Pfizer’s drug is that it targets the conserved protease inhibitor (rather than the coronavirus’ spike proteins), and is effective at doing so across strains, Pfizer is closely monitoring for the development of drug resistance.

“When you have first report of an adverse event, there will be more adverse events reported, and there’s nothing wrong with that,” Purdy said. “I think all physicians everywhere on the globe are participating in this discussion. Everyone has an important role to play, from patient to physician, from pharmaceutical company to government agencies.”

In collaboration with other researchers, Pfizer hopes to fill gaps in medical knowledge, he said, as well as to test Paxlovid’s other potential applications and constraints.

Reuniting With UVA, Through the Pill

Regardless of remaining questions, the medical community wants the public to know the primary benefit of the drug – keeping patients alive and out of the hospital – far outweighs any brief prolonging of symptoms that might occur or additional quarantining that may be required.

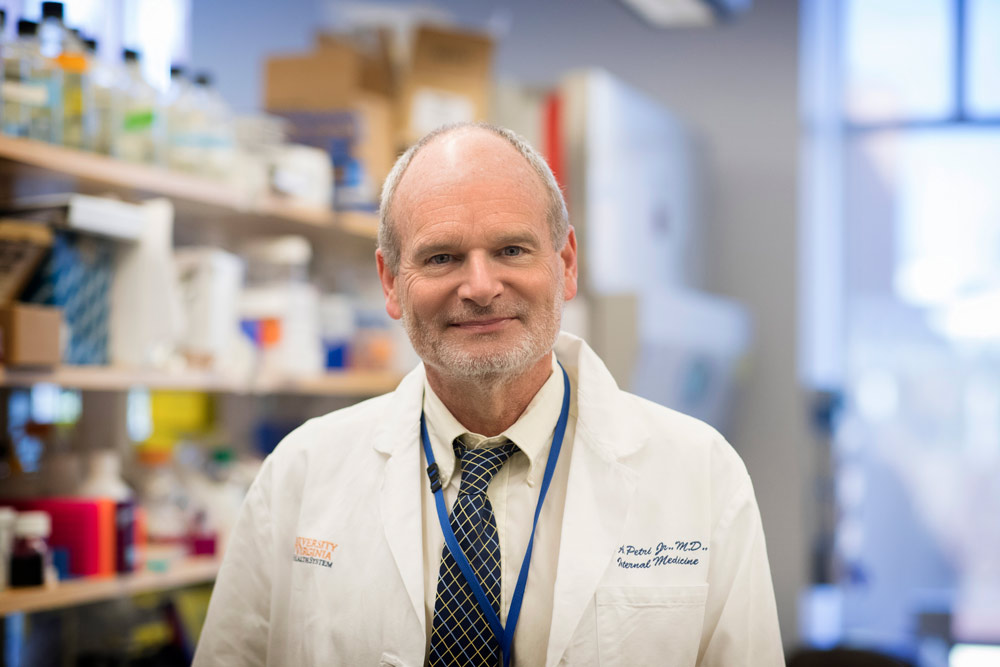

Dr. William Petri is one of those members of the medical community, and he can speak from experience. An infectious disease expert and local COVID-19 health spokesperson, he recently contracted the virus. Petri went on Paxlovid immediately – just as his national counterpart, Dr. Anthony Fauci, did last week.

Petri was proud to note that he helped develop one of the people who helped develop the drug.

“The best part of being a teacher is seeing the success of a former student,” Petri said. “I never thought I would be on a potentially life-saving medicine made by one of my former graduate students, but that is what happened. Because I am 66 years old, I qualified for Paxlovid, and started it by lunchtime. After one bad day, I was almost back to normal. I have had a bit of a recurrence of symptoms several days after stopping the drug, which is interesting, not well understood, but it was really only a minor bump in the road. Thank you, Jay!”

In Petri’s lab, Purdy explored his interest in the microscopic parasite Entamoeba histolytica, while simultaneously gaining a better grasp of how scientific studies should be designed and how to look at data critically, he said.

Purdy’s own development of “forward genetics” tools during that time period led to science better understanding how the parasite invades the gut. Since then, two published papers that he derived from his dissertation have been cited over 100 times each. Meanwhile, training he provided to international organizations studying the amoebozoans, in the interest of preventing disease, continues to be followed 25 years later.

Looking back, the vice president gratefully extoled the mentoring he received at the University, including from Petri.

“UVA gave me the basis for where I am now,” Purdy said. “It’s the foundation on which I’ve built all my other experience.”

Media Contact

Communications Manager School of Engineering and Applied Science

williamson@virginia.edu (434) 924-1321

Article Information

August 28, 2025