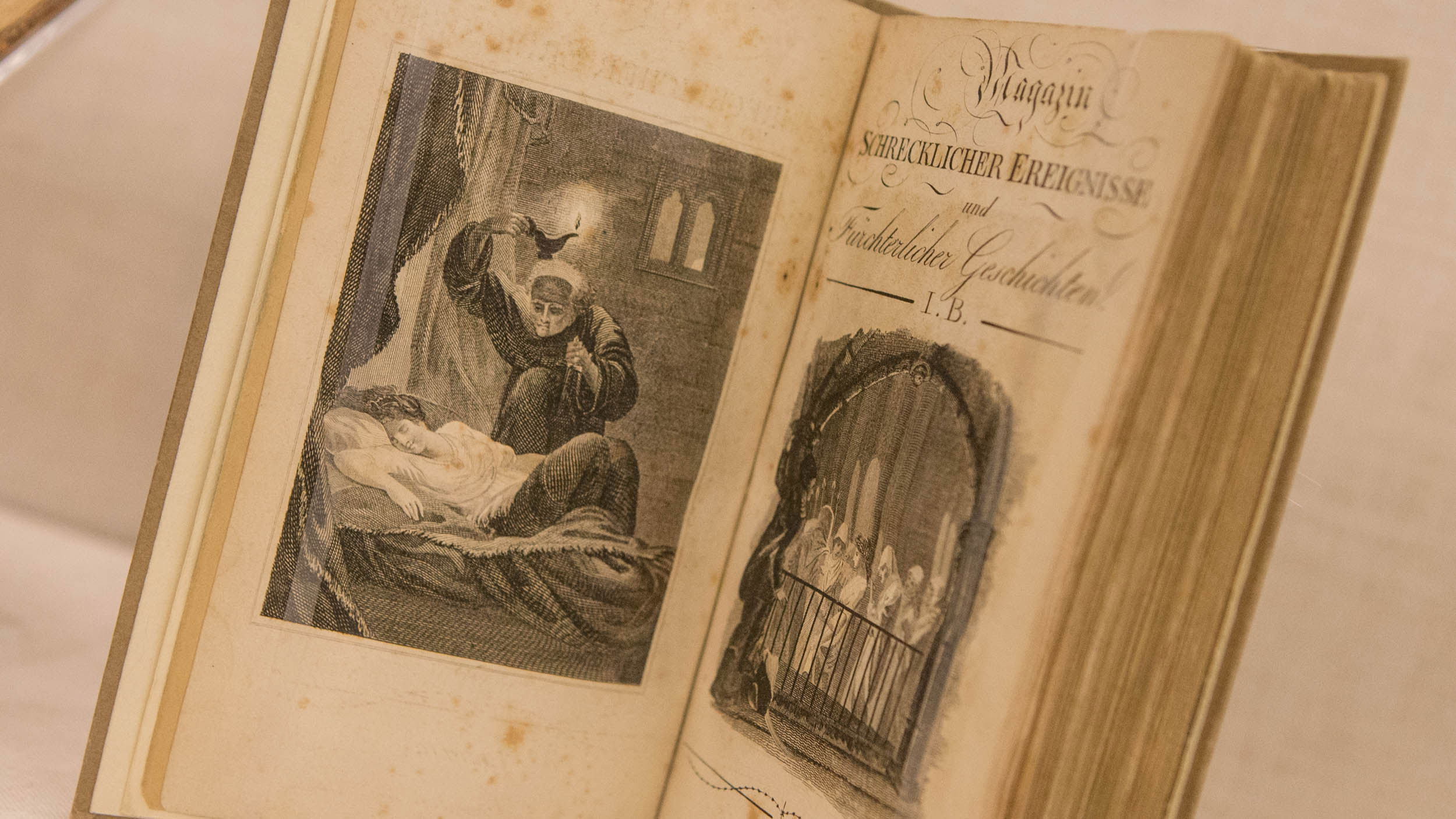

Frankenstein, Dracula, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The world’s most famous tales of things that go bump in the night can all trace their heritage to a distinct 65-year period when the British public became enraptured with the horrid. The English Gothic novel dominated popular fiction from 1765 to 1830 and spawned an endless tradition of dark storytelling and over-the-top parodies around the globe.

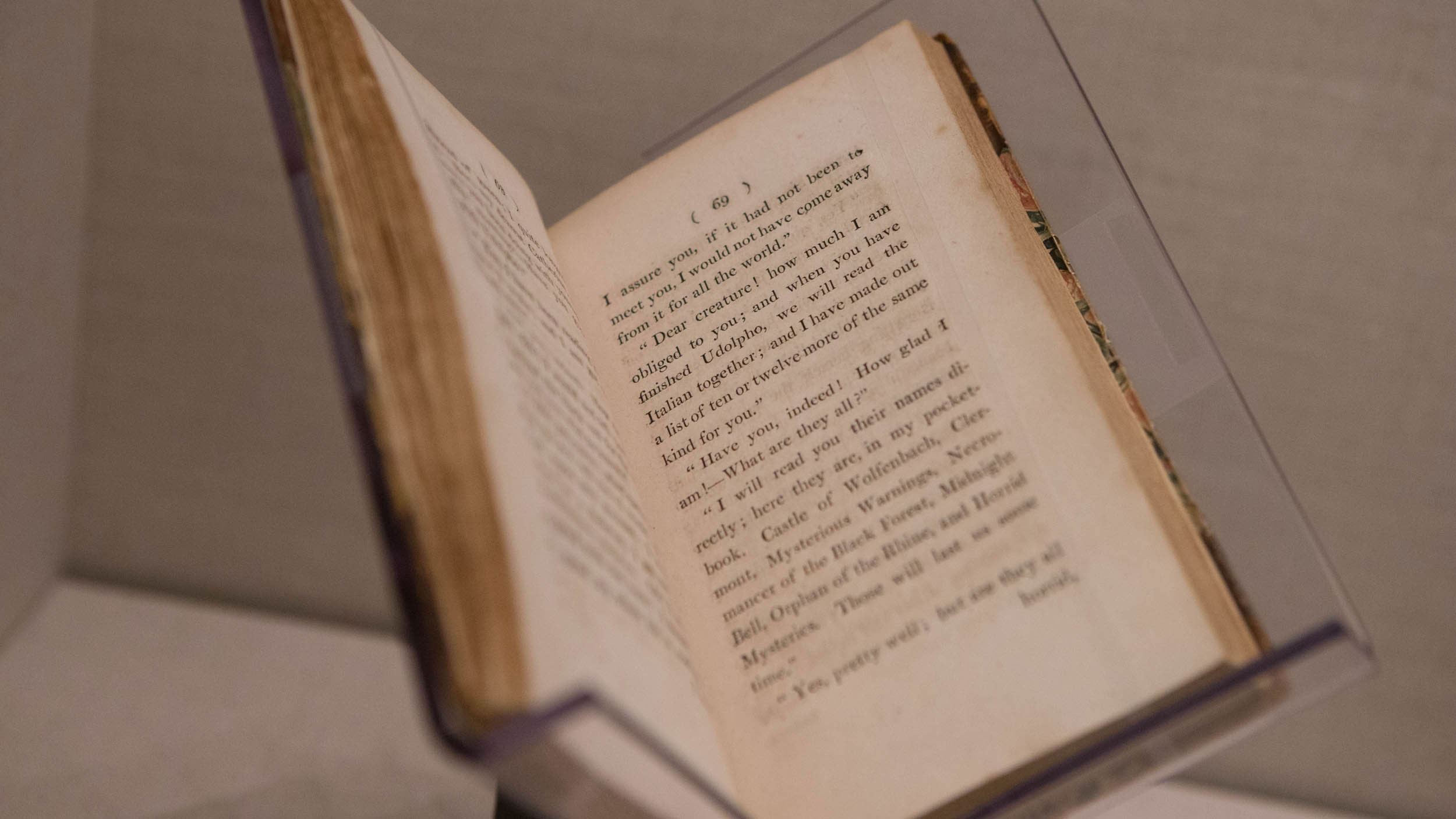

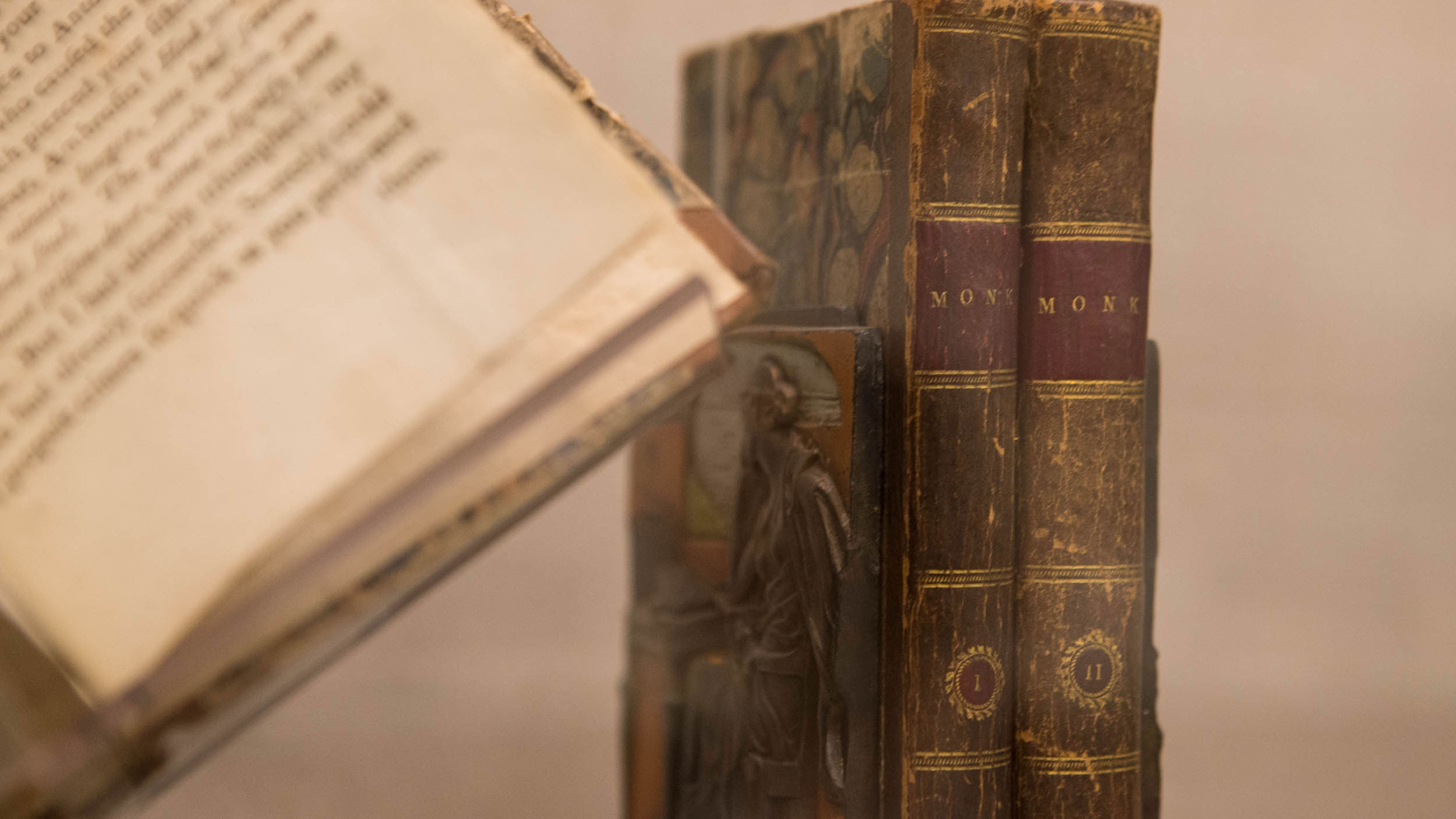

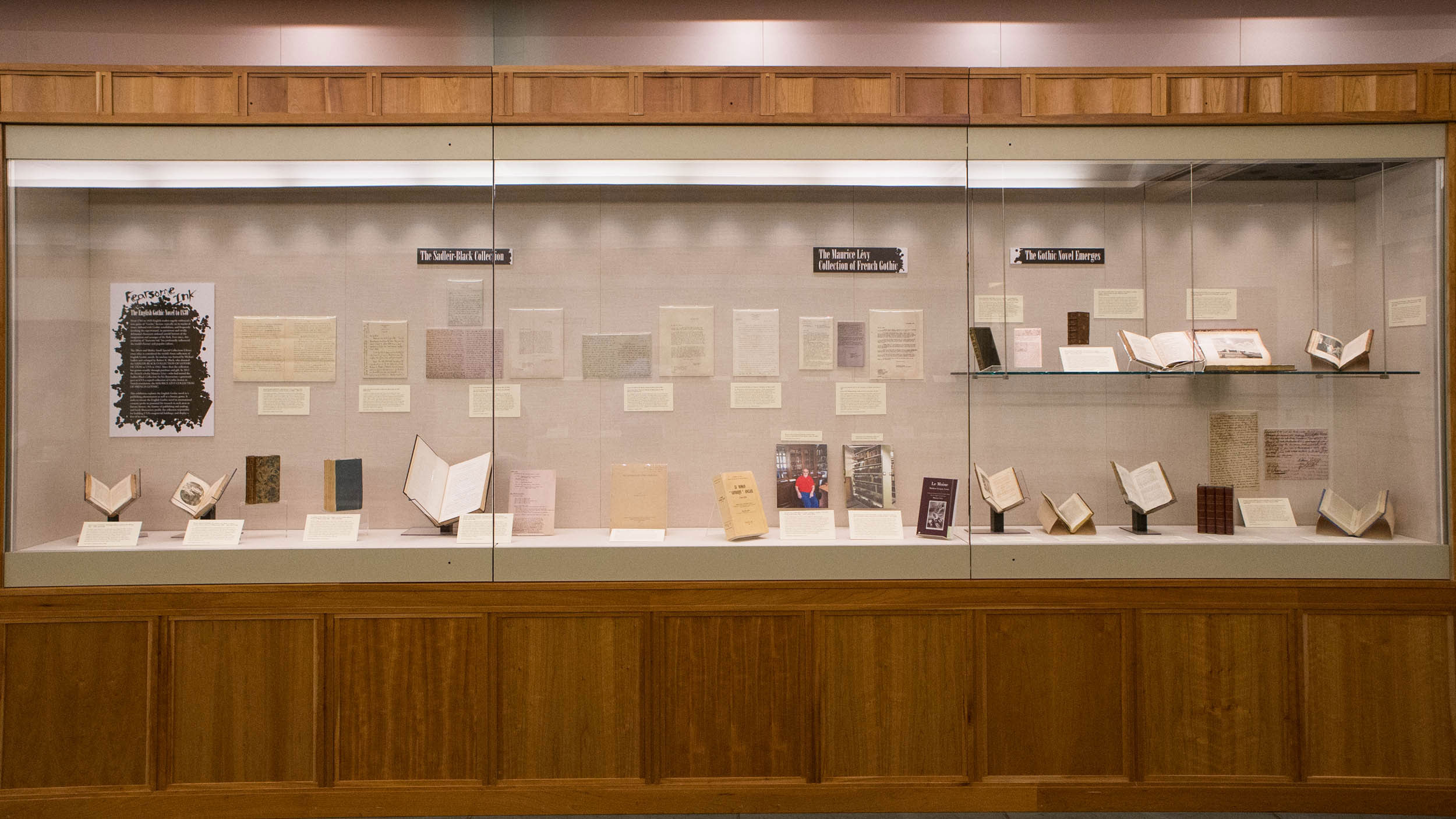

Today, the University of Virginia Library serves as the primary guardian of this early tradition. The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library is home to more than 2,500 volumes and some of the rarest Gothic novels in existence – a collection unrivaled in size and scope.

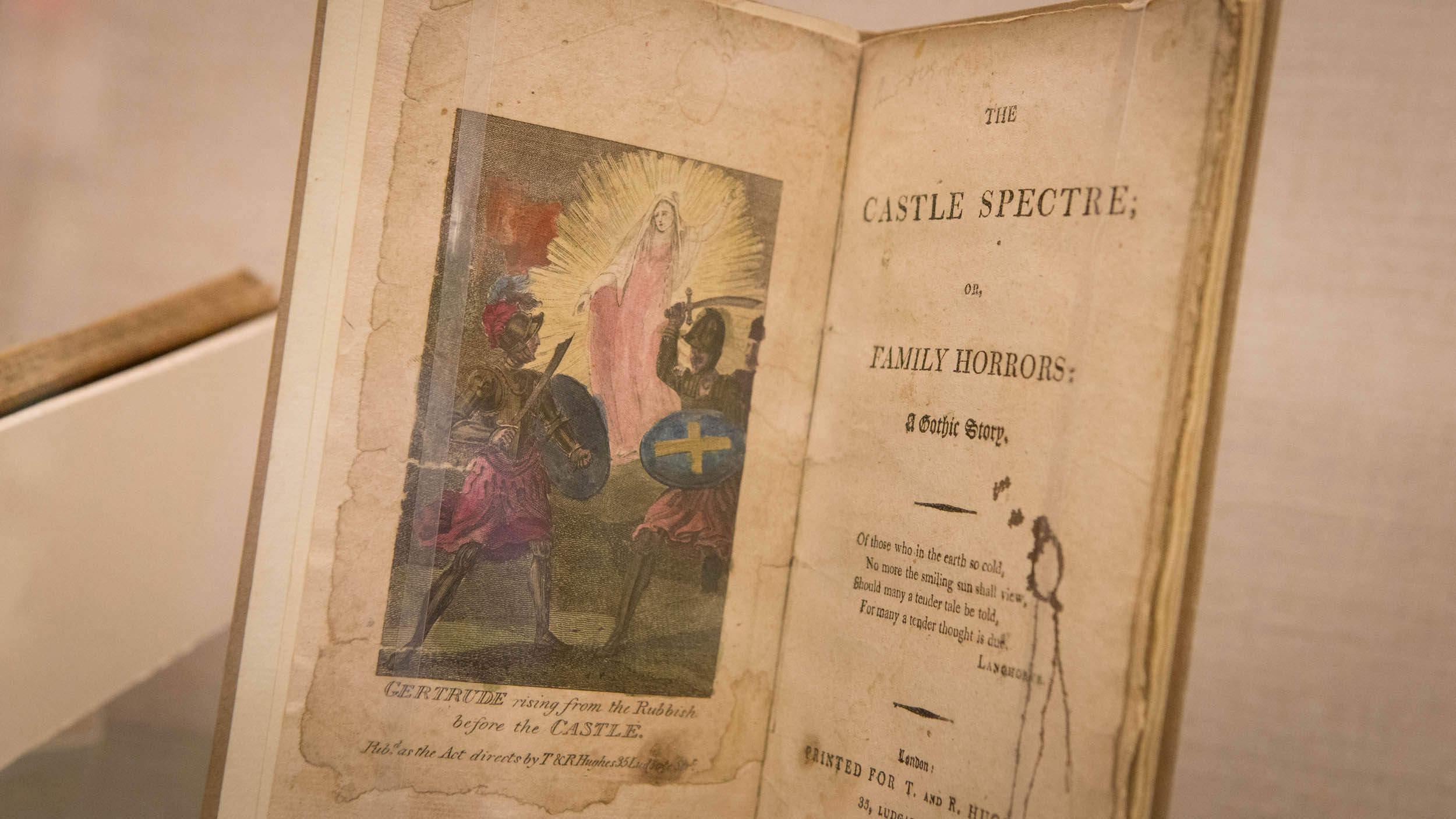

The library is currently showcasing this treasure trove in an ongoing exhibit, “Fearsome Ink: The English Gothic Novel to 1830.” It draws on the two collections that make up its formidable store: the Sadleir-Black Collection of Gothic Fiction and the Maurice Lévy Collection of French Gothic.

While Gothic literature remains wildly popular, the English Gothic novel follows a general pattern that distinguishes it from more modern tales. The stories are typically set in medieval times with highly passionate characters, invoke the supernatural, and describe in vivid detail the horrors and scourges of flesh their heroes and heroines face.