Dr. Bruce Greyson can’t say for certain what happens when you die, but he’s talked to many people with unique perspectives: They were technically dead before being revived.

“Most who have near-death experiences say, ‘I can’t tell you what happened. There are no words for it,’ and I believe that,” Greyson said. “So, I think that whatever happens after death – and I think something does – it’s so far beyond our imagination that there’s no point in trying to speculate about it.”

Near-death experiences, known as NDEs, may be hard to explain, but many have done their best to describe them to Greyson, the Carlson Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry and Neurobehavioral Sciences at the University of Virginia and former director of the UVA School of Medicine’s Division of Perceptual Studies.

Greyson is one of the world’s leading researchers into the phenomenon. He’s interviewed thousands of people and devised an internationally accepted scale to classify and measure aspects of NDEs. He wrote about his life of research in the book “After: A Doctor Explores What Near-Death Experiences Reveal About Life and Beyond.”

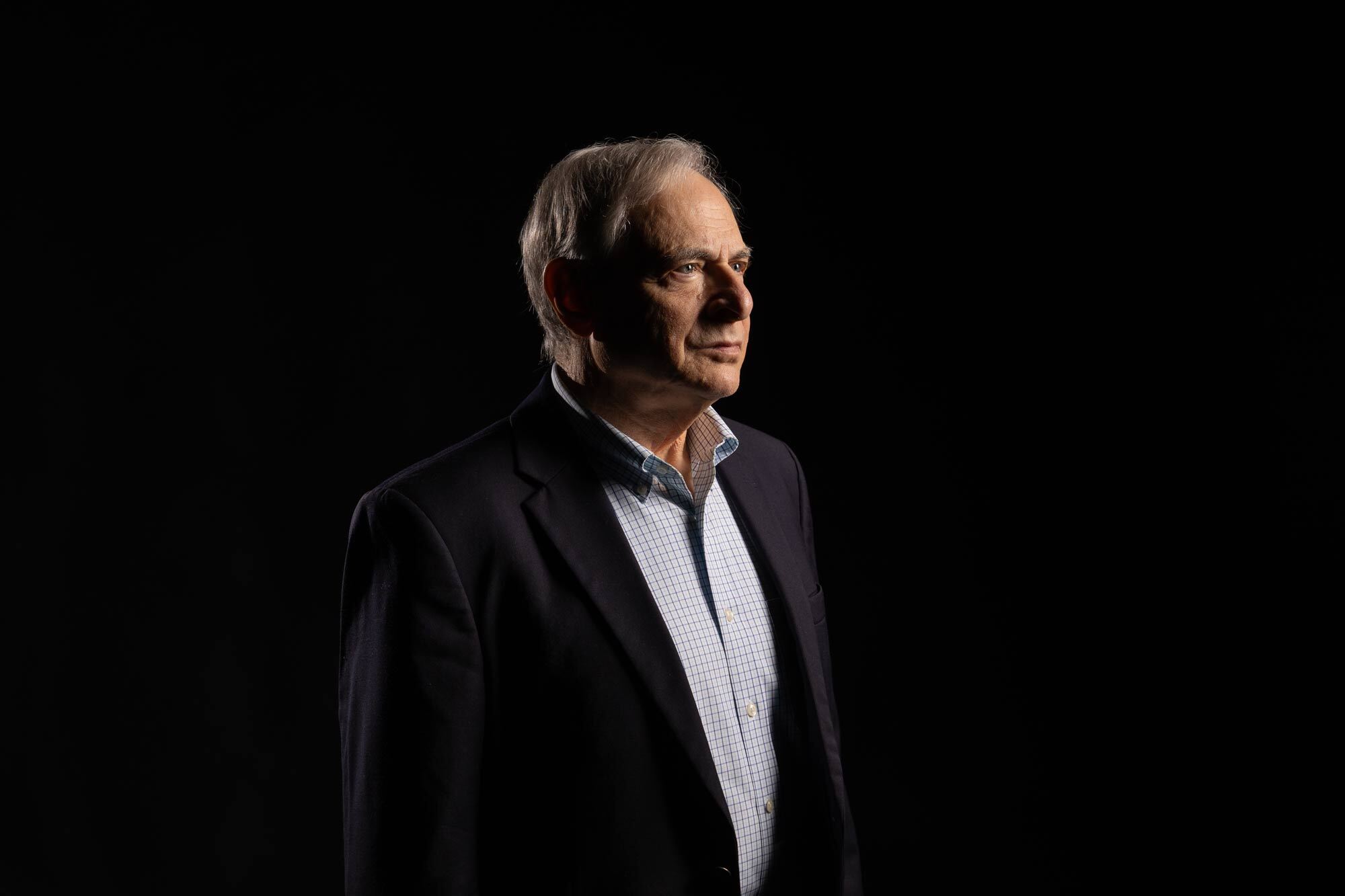

Dr. Bruce Greyson, UVA’s Carlson Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry and Neurobehavioral Sciences and former director of the School of Medicine’s Division of Perceptual Studies, is one of the world’s foremost researchers on near-death experiences. (Photo by Matt Riley, University Communications)

Part of Greyson’s psychiatric duties and his research involved talking with cardiac patients about the psychological impact of heart attacks. With those who technically died but were revived, he found the experiences not common, but not rare.

“If you interview everyone who has a cardiac arrest, between 10% and 20% will talk about their NDE,” he said, noting patients often fear not being believed or being seen as crazy. “We’re dealing with what they’re willing to say and what they can remember about what happened. There may be many more that people don’t talk about it.”

The experiences are different for each person, Greyson said, but there are similarities. In most NDEs, people experience a sense of peace. There is an altered perception of time. They often encounter deceased family, friends or beings they cannot describe. They often review their lives in great detail.

Most who report NDEs say the experience left them with a sense of peace, even those whose experiences came from attempting suicide.

“Many said things like, ‘Now I realize there’s a meaning and purpose to everything that happens to me, even the things that feel like they’re bad.’ Or ‘I know there’s a lesson there for me to grapple with and learn from, not just run away from,’” Greyson said. “Others said that when you lose your fear of dying, you lose your fear of living, too.”

When Greyson first took up psychiatry, he was very much a scientist interested in seeking the “why” in life. His interest in near-death events was sparked early in his career when a patient described events that happened one day earlier while she was unconscious and in a different room. The fact that she described him and the tie he wore the day before hit home.

It also struck him how reluctant the woman was to talk about the experience.

“Studying NDEs is important because it has implications for bereavement, for suicide, for how we think about death and dying, which in turn affects how we think about life and what we do in life,” Greyson said.

“Even if it’s only 5% of the population, that’s one of every 20 people who experiences an NDE. So, someone in your extended family or in your workplace has probably had one,” he said. “People often require an adjustment to come back into everyday life afterward, because they find their attitudes, values and beliefs changed.”