Jim Ryan, University of Virginia President:

Hi, everyone. I'm Jim Ryan, president of UVA. I want to thank you for being here. I'm joined today by my colleagues, Ian Baucom, the provost; our chief operating officer, J.J. Davis; our vice president for student affairs, Kenyon Bonner; and Tim Longo, our University Police chief.

I know a virtual town hall is not the same as an in-person one, but we're holding this virtually because we anticipated a lot of people would like to participate and we want to make sure everyone interested can join us. We also want to ensure that those who are not currently on Grounds can also join us.

I know there are a lot of questions. I'd like to start by sharing a bit of background about how we ended up where we did on Saturday. And then I'll turn to Chief Longo to provide a timeline and more background about the decisions we made and how we made them. After that, my colleagues and I will be happy to answer questions from the audience. Please use the Q&A function on your screen to submit questions. And note that you can only do this if you are registered.

So I will start with the obvious. Saturday was a terrible and terribly sad and upsetting day. It was traumatic, I know, for everyone involved. And it was far from the resolution I or any of my colleagues had hoped for. In fact, it was a situation that we had been working hard all year to avoid.

I completely understand and recognize the distress caused by the level of police presence on Grounds, especially the State Police, and I'm very sorry it got to that point. It's the last thing any of us wanted.

To understand how we reached that point, it's useful to start at the beginning. Even though Saturday's events obviously drew the most attention, the demonstration had been underway since Tuesday of last week. That afternoon, demonstrators put up tents near the Chapel. They were told tents are not allowed, which is true and is something that I'm sure we can get to in the question-and-answer period because I know there's some misunderstanding out there. They were told to take the tents down and they did.

For the next several days, the demonstrators largely complied with University policies when asked to do so, though they refused to engage directly with anyone from the administration and instead worked through faculty liaisons. They had sent it -- to give you a sense of this, they had sent a set of demands on Friday. We responded with a note inviting further conversation. And with 30 minutes, in red ink, they had written "bullshit" on our response. That gives you a sense of the unwillingness and lack of interest in engagement.

That said, things were peaceful, although they got a little tense when demonstrators brought in construction material hidden under a tarp, which at other universities had been used to barricade encampments and obviously creates a huge safety hazard. But they ultimately agreed to allow the materials to be removed. That's where things stood until Friday night. That night, tents went up, five or six, and ultimately 22.

Now, I know it was raining on Friday night, and so you need a tent if you're going to stay dry if it's raining. But we told the demonstrators -- Kenyon Bonner told them himself -- that he would be happy to stay there all night. They could go home, get dry, and come back in the morning and their site would still be there. But they refused and remained in the tents.

In addition, four men dressed in black carrying large backpacks and wearing helmets entered and remained in the encampment. At least two of these were known to law enforcement personnel as participating in violent acts elsewhere in the commonwealth. At the same time, the demonstrators were calling on social media for others to show up. At that point, we realized we really needed to get the tents down to prevent this from escalating, growing larger with potentially more outsiders and becoming more entrenched. It's a lot easier, if you have to, to move 20 tents than it is to move 75, and that's what we were worried about.

Tim Longo told the demonstrators on Saturday morning to take the tents down, and he told them if they took the tents down, they could remain and continue the demonstration. They refused and blocked him and his colleagues from the tents. Tim felt the situation was unsafe and he returned to the command center, where I was all day with senior leadership and law enforcement leaders.

We made the decision to end the protest and clear the area. We felt like this was escalating and had the potential to get out of hand. We first tried to end the protest by using University Police, hoping that the protesters would peacefully comply. But the police were met with physical confrontation and attempted assault and didn't feel equipped to engage given the situation. That's when the decision was made to call on the State Police.

That was a very hard decision, but we felt like we didn't have a safer option at that point, given the circumstances of an ever-growing crowd and defiant protesters who were continually calling for others to join them. Luckily and gratefully, no one was seriously injured. We had three reports of minor injuries, including a police officer who was struck in the face with a frozen water bottle. I'll leave it to Chief Longo to provide more detail in just a second.

I'll just emphasize, as I'm sure Tim will explain, that individuals in the demonstration were given multiple opportunities on Saturday to comply with University and police directives, first to take down the tents and then to clear and leave the area, and they refused to do so. I know many have questioned and will continue to question our decisions, and I will always second-guess them myself. It's impossible not to. These were very hard calls, excruciatingly hard. But we tried to make the best decisions we could under the under very difficult and volatile conditions. And we made those decisions with an eye toward the safety of our entire community.

Lastly, I know many of you are concerned about Final Exercises. We are moving forward as planned and will do everything in our power to make sure graduation activities happen and happen safely. I'm acutely aware that many of our graduating students did not have a high school graduation, thanks to the pandemic, and that this moment is especially meaningful for them. I have every expectation that graduation will continue as planned.

With that, I will turn it over to Chief Longo. Thanks.

Tim Longo, UVA Police Chief:

Good afternoon, everyone. President Ryan, thank you for the opportunity to attend this town hall with you and with my colleagues to discuss what happened on our Grounds and in our community last Saturday. And to discuss the -- well, it may be redundant, to discuss the days preceding our collective efforts to resolve the matter in a way that not only protected expressive conduct, but in a way that didn't compromise our University policies, our safety, or the rule of law.

Like everyone on this call and perhaps around the nation, I'm saddened and I'm disappointed. And I'm still waiting to heal and recover in a way that not only advances peace, but mends this broken trust, trust that's been compromised.

Last Tuesday afternoon, several gathered on the northwest side of the Rotunda and began erecting tents. We hadn't received any prior notice from any organizing party that this was going to take place, nor were we contacted by anyone wishing to engage in organization or assistance from either administration or from law enforcement. I immediately began walking to the area and found a colleague from Student Affairs already speaking to a person on our faculty who was there acting as a liaison on behalf of the students that were present. Together, we discussed the applicable University policy and asked that the tents be taken down. After about 45 or 60 minutes of conversation -- respectful conversation, productive conversation -- the tents, in fact, came down and the gathering proceeded without any interruption.

I should note that at that time, we were preparing for it and had been made aware of an organized event that was scheduled to take place on Wednesday afternoon from 1:00 to 5:00 p.m. Because of we were preparing for that event, we notified our critical incident management team, given the projected size of that event. That particular event occurred peacefully on the Lawn and it didn't necessitate any law enforcement engagement, engagement beyond that which it took to prepare.

On Wednesday afternoon, we observed three or four young people carrying large, partially covered items onto the Grounds into the area where the camp had been set up. We came to learn through observation that those items were wooden items frequently used for construction and are prohibited items under University policy during occurrences such as this. Along with my colleagues from Student Affairs, we were able to persuade persons within the encampment, through faculty members, to remove the items. We knew from similar events in Richmond and other areas across the commonwealth that such materials were used to construct barriers that were used to establish a fixed perimeter and prevent law enforcement intervention -- in essence, to fortify and defend an area where the camp had been established.

Throughout Wednesday and Thursday, we were engaged with faculty representatives on the site to mitigate violations of University policy regarding things like postings, amplified sound. And while we were prevented from directly engaging with these students, largely at their request, there were no apparent signs of aggression or violence.

Midday Friday, we began to see the tent structures resurface. Our efforts to have them removed were met with negative results. My message to those faculty on the scene was clear: Those present in the encampment were welcome to stay, but the tents had to come down. By nightfall, a number of tents had grown.

Friday night consisted of a religious service, much conversation, some singing. Several children were running throughout the encampment. But most troubling to me was information from law enforcement assets that were on the ground, who identified persons that were known to them as people who had been associated with previous historical events that had occurred in our community that resulted in violence. The presence of these people was accompanied by social media messaging that, frankly, had been occurring throughout the week, asking for additional people and supplies to come to the encampment.

Earlier in the evening, my assistant chief had inquired as to the availability of state resources in the event we would need them. That inquiry, in fact, resulted in their response. But based on my observations, the presence of families and children, and the absence of an imminent threat of harm, I made a deliberate and conscious decision to stand down all law enforcement intervention. Considering the approaching inclement weather, we welcomed the participants in the camp to use the porticos around the Rotunda for shelter.

On Saturday morning at about 7 a.m., I returned to the website with my assistant chief and a Student Affairs representative. My intent was, again, to ask those present to remove the tents that had been erected. After discussions with faculty members on the scene for what seemed like maybe 45 minutes or so, I made the decision to use an amplified sound device to give a series of warnings that if the tents were not removed, removal would be made by Facilities Management staff and that the tents would be stored for safekeeping until the resolution of the event. I also specifically told those in the encampment that they were welcome to remain.

Shortly after 8 a.m., I began to use the amplified sound device and gave a warning beginning at a 15-minute mark, at a 10-minute mark, and a five-minute mark. My warning was clear: The tents had to come down. They were welcome to stay, but the tents had to come down.

After about 20 minutes, I approached the group of approximately 45 people to begin the tent removal. The group clustered tightly around the space it was approaching and my immediate fear was that they would encircle myself, the assistant chief, and my Student Affairs colleagues, and so I stepped back. It was made clear to me through their voice, or at least the voice of one who appeared to be acting on behalf of the group, in each of those words, their words, they had a duty to fight for their cause. They had a duty to win, and they had nothing to lose. Their actions and words caused me to conclude that voluntary compliance with my request wasn't an option they'd be willing to consider.

I returned to the command post and I asked the incident commander and our operational team to develop a plan to use University resources and local law enforcement assets to secure the site and begin the process of executing no-trespass orders, and, if necessary, make arrests. Our law enforcement partners, to include a small number of Virginia State troopers from our area office, established a perimeter around the encampment to prevent additional persons from coming on to the site. This was especially important to me because of the social media posts that were taking place, asking for additional help, additional supplies, and additional resources.

When UPD officers returned, a series of announcements using amplified sound were made asking the group to disperse. This announcement came from a uniformed police captain. Our intention was to issue a no-trespass order, and if met with noncompliance, to effect a custodial arrest for trespass. When the arrest team went in, numerous people locked their arms and refused to separate, disperse. Officers engaged one of the people closest to them when they entered and asked that person to leave the property. Upon their refusal, that person was taken into custody and removed from the group. The officers initiated a second reentry, and there were four of them. Officers were met with the use of umbrellas in an aggressive manner. At least one person swung their hands in the direction of officers and one officer was actually struck.

The operations commander, a captain at the scene, determined that because her officers were in a standard uniform and absent any protective gear, the risk of injury was likely to the officers and others present. My fear was that if active resistance would continue to escalate, it would be met with reasonable force to overcome that resistance and the potential for escalating force was possible and likely. In consultation with members of the command post -- President Ryan was there, Provost Baucom was there, Vice President Davis was there, and many law enforcement partners -- we requested that the Virginia State Police activate a tactical field force to do a controlled operation for the purpose of clearing the compound. It took quite a bit of time for the tactical field force to mobilize and to respond. And by the time that they did, hundreds had come to the area, surrounding it.

Once the tactical field force was in place, an unlawful assembly was declared and a no-trespass directive was given. The declaration and orders were given some seven separate and distinct times before the tactical field force ever engaged. Once the field force engaged using their shields to disperse the crowd, the encampment was cleared in about 15 minutes.

Twenty-seven persons were taken into custody and charged with trespass. One police officer was injured after being struck by a frozen water bottle. There were no serious physical injuries to any of those persons taken into custody that were either visible or reported to police or medical personnel that were on the scene at that time. Persons that were impacted by pepper spray that had been used by the tactical field officers were treated by medical staff on the scene.

Over the four days that led to Saturday morning's deployment, numerous efforts were undertaken to interact with those in the encampment. The flow of information was facilitated by faculty on site, and it was made clear to me and to other administrators present that students that were there had no desire to speak directly to us.

Time and time again, we were clear in our direction regarding the University's policies and our desire to keep the matter peaceful and compliant. We consistently sought compliance and unequivocally offered to allow for a peaceful, expressive conduct to continue. When I arrived at the site Saturday morning, it was my sincere hope that I would be able to gain compliance. That didn't happen. Despite clear and unambiguous direction, I was met with both words a conduct that quickly caused me to conclude that it was the intention of those present to continue to occupy the space on their terms.

I yield to you, Mr. President.

Ryan:

Thank you, Tim.

So we have a bunch of questions teed up. I will read them and either answer them myself or suggest someone to answer them. I think this first one is for you, Kenyon. Why didn't you engage with the students -- you can start anyway -- and why didn't UVA follow the path of Brown University, whose administration made a good-faith effort to start a dialogue with their student protesters and reach consensus peacefully?

Kenyon Bonner, Vice President and Chief Student Affairs Officer:

I'll start with, we began attempts to engage in dialogue with the students on April 30th, which would have been Tuesday. It was clear from the individuals who are students they did -- they indicated that they did not want to speak to Administration, and at that point the faculty established that they would be the, sort of, intermediaries between us and the students, um, we then sort of agreed to comply with that to deescalate the situation and began to communicate through the faculty and made several attempts to have conversations with the people we believed who were students within the encampment. I offered personally the opportunity to meet with the students.

It may have been on Wednesday, the faculty member said they would take that back to the students. I visibly saw the students gather in a huddle for a few minutes, and the faculty member came back and said that the students did not want to talk to administrators and me specifically.

In addition to those attempts, my Student Affairs team and myself set up shifts to just be available around the clock. My shift was 2 a.m. to 6 a.m. to be around in support and working with the faculty, and to be accessible, in the event that students wanted to have a conversation or engage in dialogue. And that never occurred. Yet we continue to engage with the students.

On Friday morning at 4:45 a.m., I walked over to the site, talked to the faculty member who was on duty. And a student came over and handed that faculty member a document. The faculty member handed it to me. And it was their list of demands. They said that they expected a response.

One of the demands was a response by noon. At that time, I indicated to the student and the faculty member that noon deadline would be a challenge, but I would do my best to meet it. And if the latest, 5 p.m. -- we were able to respond to those demands by 4 p.m., all of the demands I thought thoughtfully and carefully.

And also extended within that document a continued invitation to engage with us in conversations and dialogue about their concerns, their requests, their demands specifically. I think President Ryan already shared what their response was.

So there were repeated and continual attempts throughout the entire week to have conversations, but the students were very clear that they did not want to speak to administrators. And it was a difficult situation to manage without having the opportunity or the willingness from folks to engage with us.

Ryan:

The only thing I'd add to that is there is a group of students, an affiliation of groups around the issue of divestment that helped organize the referendum that have been engaging -- I don't believe there was any connection between those groups and the groups protesting by the Chapel, but they have been engaging both with Kenyon and Cedric. And I've had a meeting on the books with them for a couple of weeks. So there has been engagement. And we have been open to conversations. I've made my view about divestment clear, but I'm completely open to hearing other perspectives.

So next question. This is for both me and Ian.

Where were Jim and Ian? And why didn't they appear at the site of the protest to try to maintain calm?

So we just talked about the attempts at engagement. By the time the police activity was occurring, given the stance of the group, my view was that my presence would inflame the situation, rather than de-escalate it. It's also the case that if I'm there, police have to be paying attention to me rather than the situation at hand. So I was, like I said, in the command center all day. There was a live feed of the protest, and we were trying to figure out how we could bring this to a peaceful resolution.

Ian, do you have anything to add?

Ian Baucom, Provost:

No. I think the only thing to add is it felt important to be with Jim, be with the president, have his senior leadership team. There was a lot of information flowing in.

As Jim has said, it was a very fluid situation. And just felt like we needed to give him the best counsel we could.

You know, there's a lot of -- I also just want to acknowledge how aching the situation is, and how fully he is --

The president began with, if you begin at the end, none of us wanted that end.

As we walked through the pieces of it, we were just trying to make the wisest, best decisions we could, fallibly, but the best decisions that we could. So I've done a lot of replaying in my head. I think we needed to be there for the president. But that's a replay in my head.

You know, you ask, you know, could it have made a difference? And that's gone through my head. But that was the call that seemed like the right call over the course of a long and complex day to be able to give Jim the counsel he needed.

Ryan:

The next question: President Ryan's letter indicated that the protesters had been told several times that they were violating UVA rules, but they continued to do so. Our daughter, a third-year student, insists that the rules were changed "only shortly before police started taking down tents." Could you clarify what happened?

So I know this is a little confusing and some of it is our own fault, but it's very clear that tents are not permitted. There are two different policies that apply.

One is a policy that prohibits tents on a list of prohibited items, whenever there's an incident or occurrence, which includes demonstrations and protests. That list also includes construction materials, which is why we asked the demonstrators to remove the construction materials.

There's no doubt that the law enforcement have the ability and exercised that ability to prohibit tents. And I don't think there is any confusion among the protesters about whether tents were allowed either.

There's a separate policy that says you can't have a tent unless you get a permit first. And then it links to the place that issues the permit, which is the Environmental Health and Safety office. I'm not sure if that's exactly the right name. They have about 18 rules about what you need to do if you get a permit and where you put up your tent and all that.

And they had listed on the first bullet, after saying tents need to be permitted before they can be erected, that this doesn't apply to recreational tents. That's inconsistent with the policy, which says that all tents need to be permitted.

So someone on our team, and I'm not sure this was the right judgment, at 9:30 or so on Saturday decided to remove that, so that those rules were consistent with policy. But it's immaterial to whether tents were allowed because the first policy clearly applies.

And if you look at the rules on the Environmental Health and Safety website, one of the rules says tents can't be within 20 feet of a building, 20 feet from each other, or under a tree. And given the placement of those tents, most, if not all of those rules were being violated. And last and least, not all the tents were recreational.

But I think the most important point is I don't think anyone involved thought that tents were allowed, because they're not. And that was not the claim. I think the protesters knew that the tents weren't allowed and wanted to keep them up anyway.

All right. How many people were arrested? And how many were students?

J.J., you have the figures for this.

Jennifer J.J. Wagner Davis, Chief Operating Officer:

Yeah. Thanks, Jim.

So in total, 27 individuals were arrested that day. Twelve of them were students. Eight were unaffiliated, not related or part of UVA, either students, faculty or staff. I think a particular note of one of the eight unaffiliated was also charged with assault. There were four employees, and then three former either employees or students, for a total of 27.

Ryan:

All right. Next question.

What punishments are students facing? Are you going to rescind the NTOs? Chief?

Longo:

Yes, sir. So I made a modification to -- I made a modification to the no-trespass orders yesterday, allowing students to complete their exams, remain in their dormitory spaces until such time as their academic obligations are over.

With respect to those fourth-years, again, allow them to take their exams, participate in Final Exercises, stay in their dormitory placement until such time as Final Exercises are over.

And then we continue the no-trespass through the summer and with the stop date of the beginning of the fall semester.

It might be worth mentioning, we exercise our no-trespass authority often, and particularly in association with arrest. And it's not unusual for me to either rescind or modify a no-trespass order. We do it with some degree of frequency. We always look at the background of the individuals, whether they've been involved in the criminal justice system before, whether they've ever presented, and our threat assessment docket, and the facts and circumstances which led to their arrest or the issuance of the NTO. So it's a fairly common practice we engage in.

We also modified the no trespass orders for faculty and staff.

The no-trespass orders for unaffiliates will remain in effect for a period of four years.

Ryan:

All right. Thanks, Tim.

I've just learned there's some technical issue with the livestream, and I understand our team is working on it. And hopefully it will be back up very soon. But everyone should know that this is being recorded and will be posted publicly if you've had trouble.

OK. Ian and Kenyon, you can start on this one.

What actions did leadership take before the assembly encampment began to create a space, opportunity for dialogue between opposing views in an effort to cool the waters?

Baucom:

Sure, happy to jump in.

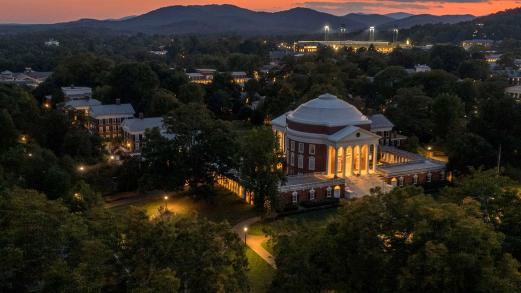

So, as Chief and Jim have recounted the encampment itself, we didn't have any warning that it was coming. So there wasn't a particular opportunity with this event. As it turned out, the president and I were actually in the Rotunda at an award ceremony for faculty and looked out the window, and saw that the tents were going up.

Immediately, at that point, Student Affairs engaged, people from the provost's office engaged. So really, within minutes of seeing it begin to happen, we're out there talking, talking with the faculty members, again, getting the response back from the students. They didn't want to direct engage with us, but the faculty sort of served as liaisons. So there was no pre-notice, but we moved, I think, within minutes of it starting.

More broadly, as Jim has said, over the course of the year, we have been meeting, Student Affairs has been meeting, the president's been meeting, I've been meeting, with students, faculty or staff.

But I'll just focus on students, you know, who are in the midst of this wrenching conflict in the Middle East. We've been meeting with Jewish students, with Muslim students, with Palestinian students; Kenyon and his team have been convening dinners together, just trying -- committing absolutely to what the question asks.

You know, how can we have peaceful, thoughtful, constructive dialogue? How can we get voices together? How can we be in a room and sit and listen? What do we need to learn, how can we embrace, how can we engage?

The University, as many of you know, has pulled together a task force that Dean Acampora is chairing on religious diversity and belonging, with the goal of understanding what is the nature of the experience of minoritized religious groups on Grounds.

What is it like to be Jewish or Muslim, or Hindu, or belong to another religious minority at the University? How can we more deeply engaged not just in these really hard months, but commit ourselves over a long time? What kind of academic offerings can we provide?

So whenever possible -- and again, we're imperfect, but whenever possible, we have been consistently trying to do this and brought the same spirit.

Ken, I'll turn to you, but I think brought the identical spirit of wanting peaceful engagement and dialogue as instantaneously as we could, and then for, without interruption for the five days that followed, and then leading up to Saturday.

Kenyon, I don't know if there's anything you want to add.

Bonner:

Yeah, I'll just add something.

This was said earlier by President Ryan.

You know, I don't think it's accurate or fair, or reasonable to conflate the students that we've been in dialogue with all year -- at least since I've been here and before -- and who've been advocating for Palestinian rights and hosting rallies and demonstrations on Grounds peacefully and following University policies.

And the individuals who participated in the encampment -- I didn't recognize any of the individuals that I've been in communication with, with our dean of students, and other members of the administration throughout the year, having really thoughtful, engaging conversations and discussions, not always agreeing, but agreeing to disagree and really establishing a relationship to work through their concerns and interests. And so I wanted to just underscore that point and be clear.

I am immensely proud of our students who have exercised their rights within our community, and respected the rights of others, and worked with us to follow University policies. And what we experienced with the encampment since Tuesday, and particularly on Saturday, is the polar opposite of the activity that the other student organizations and students have done on Grounds. And so I just wanted to be clear that these are -- it's not fair or even reasonable to suggest that these students are the ones that we've been talking with.

And I did not identify any of them that I could see during that time.

That's all.

Ryan:

Yeah, I would just underscore all of that. I mean, and Kenyon and Cedric, our dean of students, and have spent an awful lot of time with students. Ian and his colleagues have done an awful lot to offer opportunities for not just dialogue, but hearing from experts.

I have met with a number of different student groups. So there have been a lot of conversations, like I said, at the very beginning. In some ways, all of our efforts this year were leading towards a very peaceful year, in a year where there were opportunities for students and faculty with different views to have conversations with one another. That's what universities do best, and that's what we were and have been and will continue to try to do.

All right.

Did the administration consider that the message of the protest was more important than the violation of no-encampment law?

So the no-encampment law, along with other University policies, fall in what people usually refer to as "time, place, and manner restrictions." And these are restrictions that protect free speech, but also allow for the University to function and protect the rights of everyone to participate in the life of the University, and to have their voices heard as well. In my own view, if you start to make exceptions based on the content, you're lost. Because if you make one exception because you believe the cause is very just, you're going to be faced with other instances where you have to make the same decision. I think our only choice is to apply them consistently and without respect to content. Otherwise, you're going to be picking and choosing among -- you're going to be picking and choosing among causes.

But I also want to say, this was not just about some technical violation of tent policy or no encampment policy. This became a safety and security issue, especially when the four men came in on Friday night. So it wasn't just about enforcing what might seem like a silly bureaucratic policy. It was about a safety -- It was about a safety risk, from our perspective.

All right.

This is related to what I was just saying. And, chief, I think this is for you.

What threat did maybe two dozen students with tents present to the University?

Longo:

Well, I don't think two dozen students with simply tents presented any threat to the University. I can tell you that having spent three or four days closely aligned in that encampment, visited several times a day, engaged with the faculty members there, spoke with my colleagues that were there, spoke with citizens, constituents that were walking back and forth, I didn't feel fear. I didn't feel that Friday night, either, which is why I was very direct about standing down law enforcement resources.

But when I went to that site Saturday morning, I've got to tell you, I expected a different interaction. I was in fear when that group surrounded those that encampment, opened up the umbrellas, use words such as "fight," "win," "nothing to lose," "at all costs." I was afraid that, at the time, that myself and the assistant chief and the Student Affairs colleague that was there would be surrounded, and that we were would be put in a position to have to defend ourselves. It was clear to me, by word and action, this was escalating, and I was concerned. You know, we took steps by using our own University Police Department, and no one else, to go in, to engage, to enforce not just our policies, but the law -- and were met with active resistance.

And so it wasn't about the tents. It was about the behavior.

Ryan:

This next one is also for you, chief.

Did the University authorize the use of tear gas on student protesters?

Longo:

No. And tear gas, in fact, was not used. What was deployed by the Virginia State Police was a chemical irritant called pepper spray. It's very different than gas.

In fact, in the command center, when the tactical field force arrived and the captain who oversees our area here, our region, in fact, for the Virginia State Police, who was present -- I specifically asked him to direct the tactical field force not to use gas on our Grounds. And they complied with that directive.

They used pepper spray. Pepper spray is a very different chemical irritant. And as I indicated in my remarks, any persons who were exposed to that pepper spray were treated by medical personnel -- it merely is a water-washing-of-the-eyes treatment that takes place. And that was done at the scene by medical personnel.

Ryan:

All right. Next question.

Hi, there. I've been seeing a lot of comparisons to the admin police reactions of this event and the 2017 Unite The Right Rally. As someone that is relatively uninformed on the admin workings behind the two 2017 event, could you shed some light on why those events were handled so differently? I understand not everyone on this panel was in their positions in 2017, but I'd like to better understand the thought behind these reactions. Thank you.

So I don't think -- none of us were in our jobs in 2017. So I'm not entirely sure what this is referring to, but I will say two things.

One is after 2017, there was a review of what happened and a number of time, place, and manner restrictions that didn't exist, especially around the Lawn and the Academical Village, were put into place. I think there was a sense that there were some gaps there in rules to protect speech and protect the safety of the community.

The other piece is that, you know, part of my own thinking with this, as a Friday night, when we were hearing calls for more people to show up, and we saw these four guys who had participated in violent protests before, I thought about 2017. And I think, in hindsight, some of the difficulties with 2017 was not reacting quickly enough.

And so I was thinking that if we don't act and we don't move, and we just let this unfold, are we going to be faced tomorrow with not 22 tents, but 50 tents, or 75 tents and with 20 outsiders? And then where will we be? So it's risky to act at any particular point, but it's also risky to sit back and watch, and wait.

I don't know whether Ian or chief, you have more to add.

Longo:

Mr. President, I'll just add a few more points and then yield to the provost. I wasn't part of any of the planning, coordination or response in 2017. I sat on the sidelines, like many others in this community, and watched the circumstances unfold. I will tell you that it's my understanding in that case, there was a lot of intelligence in advance of it.

One of the other things I think broke down there that we were particularly concerned about focusing on here in our preparation was the whole aspect of unified command. The various law enforcement agencies that were represented here on Saturday morning, the leadership of those law enforcement agencies, or a representative of the leadership of those law enforcement agencies, were in our command post. Every decision we made along the way was made in a unified, collective way, so that as we deployed our resources, there was alignment with how those resources would be deployed, the rules of engagement that they would use during the course of their deployment, to ensure that the message was very clear as to how we would go about our work.

I can't say that happened in 2017. It didn't appear to me that was the case, but because I was not part of it, I can't say with any degree of certainty.

Baucom:

Only thing I'd add is I wasn't provost, but I was dean in 2017 and participated in an extensive review of the University's actions that Dean Goluboff, Dean Risa Goluboff of the Law School, chaired.

And Jim, just to underline a couple of your points, one of the things that we discovered was precisely that we hadn't kind of readied the Grounds. We hadn't readied the University with time, place, and manner restrictions that would have enabled us to step in earlier to secure the University at that moment. And a big takeaway was we really needed to think about how to do so moving forward, to have the University ready to do everything we possibly could for something like that, not to repeat.

So there was a lot of work that was done to think about how do we do this, how do we establish designated protest zones, how do we make sure that we're protecting the rights of our students, faculty and staff, how do we think about affiliated and unaffiliated people. And much of that, I think, sort of informed our thinking about this, and I think sort of gets to one of the points that you've made as another lesson on this is, you know, you've got to be content-neutral and consistently apply the policies, so that we're in a position to do so moving forward, regardless of other situation we have, where we're going to protect free speech, we're absolutely going to do it. But we have to be able to, in a moment where we think that there might be a safety risk to the community, be able to work through those policies with that in mind.

Ryan:

So the next question is, do you believe that protesters are always obligated to follow the established rules, even the rules against which they are protesting? What should protesters do when their moral duties contradict their legal duties?

So I think this is a really fascinating question, and it's one I've thought about a lot. And the way I think about it is you've got a few different categories

One is just traditional free speech, where you are obviously free to protest, assuming that you're abiding by time, place, and manner rules that apply to everyone equally.

Then there's civil disobedience, which has a long and honorable tradition, where you feel so passionate about a cause that you're willing to break the law and suffer the consequences.

The exercise of peaceful civil disobedience by people like Martin Luther King Jr. or Mahatma Gandhi, like I said, has a long and honorable tradition, but the key is it's peaceful. So part of what we were thinking with the students was they were going to engage in civil disobedience, and when the university police showed up that they would voluntarily get arrested. That's what we thought would happen, and it didn't.

That leaves the last category of not just engaging in civil disobedience, but in violating the law and resisting an attempt to be arrested. That's a very different category. And in my view, protesting in a way that even if it involves breaking the law, is still peaceful, is completely honorable, if someone has decided that that's the path they're going to follow.

All right, next one. J.J., this is for you.

Can someone speak to the use of Facilities Management to block roads and clean up the encampment? It feels unreasonable to ask UVA employees to do the work of law enforcement.

Davis:

Thanks, Jim.

So by way of background, as Tim and Jim have talked about, we have a critical incident management team and Facilities Management was part of it.

In the earlier days, there were multiple policy violations, and the Facilities Management team was part of, for example, taking down signs and other things, cleaning up debris and so forth.

In this instance, as the situation unfortunately escalated, we attempted first to work with the Facilities Management team to peacefully attempt to take down the signs. As the chief has indicated, that was met with significant resistance and unsafe. So we did ask the Facilities Management team to step back.

We are in concert with the Facilities Management team, asked if they would be comfortable in this regard and they were, to the end result, where Facilities Management assisted and the clearing of the encampment that was only once the scene was stabilized. So we did not put any University employee in harm's way.

Ryan:

All right. Next question.

Is it possible to engage students and faculty on both sides in a discussion that would also include educating participants on the facts, on events, and history in the area of the Middle East?

Ian, you want to start?

Baucom:

Yeah, so absolutely.

And it sort of goes to one of the things Jim said earlier. That's what universities do. And throughout this, we have been trying to think about what it means to be in the midst of this terrible conflict in the Middle East, as a university, as educators.

So with deep thanks to many faculty, students, staff, deans, colleagues in the provost's office, beginning in late October, have been running a series of talks, events, conversations, public fora exactly on this. Exactly on this. And if you want to take a look, you can go to the provost website and see a list of events -- many of which we can't take credit for organizing, but we've been trying to publicize those.

Just to the middle of last week -- I forget whether it was Wednesday or Thursday. The Miller Center and the College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences organized an event that brought in two faculty members from Dartmouth who've gotten a lot of really positive attention, scholars of Israeli and Palestinian politics, to talk about how they do this work.

And as I mentioned, the work of the task force that we've done together on religious diversity and belonging, one of their explicit charges was to say, "How can we not only over the course of this academic year, but moving forward, commit ourselves and institution to continuing educational engagement, to sustaining it, and to making the kinds of commitments that we need to make for continued lectures, continued symposia, continued support of faculty?"

We're waiting for the recommendations of that group. But I can absolutely tell you, it is our firm intention that if they make recommendations, which I think they will, that we provide additional support for that kind of important intellectual academic work and modeling civil exchange. We will do so as an institution.

It's one of the ways in which we can try to, you know, really think, be, live, and learn together and are committed to doing so.

Kenyon, I don't know if you want to add any more, because there's also an addition to the academic component. There is the student life component of how you've been doing this work.

Bonner:

Yeah, what I'll add is some of those programs are hosted by our student organizations, which those have really been helpful to the student body. And so student organizations have been, and continue or probably continue to, host programs that are educational in nature, and invite members of the community to participate in that learning and conversation.

The dean of students and I had a meeting with several students about a month ago, including Palestinian, Muslim, and Jewish students. And the main thing that they were helpful with was providing feedback on ways that we can construct opportunities for students next academic year to get together to learn how to engage in dialogue, build trust and rapport with each other, and equip students with the skills and the comfort to increase the intensity of those conversations. And so there was a recognition that that's not something that's necessarily taught, and there's limited experiences that students have in having that type of conversation and dialogue. And so that feedback from our students, many of them student leaders, was really helpful and informative. And so we'll be working with those students who are interested in continuing that, as well as other colleagues, our Karsh Institute on Democracy, as well as our Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, to develop that type of program, cohort-based program next year for students.

So there's a lot that we've been working on. There's a lot that our students are doing, and there's a lot that our academic colleagues, faculty, researchers can provide to that effort.

Ryan:

Thanks to both of you.

Can you say more about the threat posed by outsiders who joined the encampment, chief?

Longo:

Social media is a blessing and a curse. Anytime you use it for any reason, the audience is tremendous. And certainly, the fear that we had when so much of social media posted involved welcoming people from the outside onto our Grounds and into our space.

It's hard to know who's going to respond. But what we do know is this: through our intelligence sources on the ground, that at least four persons who responded were known to law enforcement. At least four persons who responded had been engaged in organized work in the past around historical events that have occurred here that resulted in violence.

All we have to do is turn on the TV every night and look at violence around our nation and around our world. There are people who are disruptive who will come to events like this for the sole purpose of creating a disruption that oftentimes result in violence. So that was our fear.

You know, law enforcement oftentimes organizes and plans around intelligence information, information that we receive from law enforcement entities across the commonwealth. And in this case, we did that, and have done that since October in each and every incident that we prepared for. And when our resources started to get a sense of these types of persons showing up at this event on our Grounds, it becomes part of our calculus when we're doing our threat assessment as to how we will respond. And the numbers were growing. And as you can see, just by looking at video, by the time that the terrorism -- that the field force had arrived to begin their work, I mean, there were literally hundreds and hundreds of people who had come and who had gathered, perhaps many of them by way of that social media invitation.

That bottle that struck the officer in the face came from that group, from that crowd, from that group of people that was drawn here. So those are the kinds of things, the fear factor, if you will, of violence that concerned me and that frankly, concerned me throughout the week.

And I hope that's responsive to the question.

Ryan:

The next question.

What resources are available to students, faculty, and staff who need support in the wake of this?

Why don't we start with Kenyon, and then go to J.J. and Ian.

Bonner:

Thank you.

Yeah. So obviously, anytime there's a situation where a large number of law enforcement have to disperse a large crowd, that's disturbing to a lot of students. It does impact students emotionally. People question their safety and have different views on why that had to occur in their community. And so in recognition of that -- I know that there have been many students that I've spoken to who've talked about the impact it's had on them personally. And as the president said, that's not the type of environment or feeling we want any of our students to have.

We also know that, you know, that's not something that we can control. And it's important to have resources and support for students. And so yesterday we did send out to all students a list of our resources reminding students of our CAPS, our Counseling and Psychological Services; our Timely Care, which is a 24-hour option for students to call if they need to talk to someone; and our care and support services offices, which offers support to students. Included in that email, we included information about academic accommodations for students who may have been arrested or were just bystanders and affected by Saturday.

And so all those resources have been sent to our students. There are resources that have always existed, and we hope that any student who needs them, please, utilize them as much as possible.

Davis:

Yeah. And I'll just follow up, Jim.

We do have a FEAP, which is Faculty and Employee Assistance Program. It is staffed. It is confidential. It is free to both faculty and staff across Grounds. And it's a comprehensive set of services, whether you want one-on-one or you prefer telemedicine. But really, it's a resource that we have and we've stood up with additional staff to support our faculty and staff who, again, as Kenyon said, may have witnessed the incident, may feel triggered by any previous incidents, or perhaps what's going across the nation right now. So they are trained counselors. And again, it's both free to our entire workforce and confidential.

Baucom:

Only thing I'd add is we wanted to be sure to communicate as broadly as we can about this. Sunday evening, I was in touch with all the deans, shared a resource, kind of a comprehensive resource of all of these services that are available to faculty, students, and staff to ask them to share with their University community. We met with the deans first thing Monday morning, both in the message sent out Sunday night and in our conversations Monday, I know the deans have been following up encouraging faculty to show academic flexibility.

We know that we're in exam season. We're in exam week. It is a faculty decision to make. I do want to reinforce that, but encouraging them to show flexibility. We know that there are a lot of people, you know, for whom this is really kind of traumatizing, and want to care for our students as best as we can.

Ryan:

We're getting near the hour, so I think we'll make this the last question.

How will UVA encourage future student civil engagement and exercise of free speech? How will we prevent UVA from becoming a space which does not encourage students to think critically and act on their own moral compasses?

So I'm happy to start, and then, Ian and Kenyon, if you want to chime in.

I would go back to what Kenyon was suggesting earlier, which is that this particular event was an aberration. And all year we have been making space for free speech and civil discussion. We have given it a particularly wide berth and have faced criticism for doing so.

But UVA's commitment to free speech is a bedrock part of this place, which is why a couple of years ago, we drafted a statement of principles about free speech. And all the events that we have been hosting this year -- inside the classroom, outside of the classroom -- are all about civil engagement. And many of them have featured differing perspectives.

So I don't look at this particular event as a threat to what UVA has been doing all year and working really hard to do, and will continue to work hard to do.

Baucom:

I think that says it perfectly. It's written into our DNA. Just two things, maybe, to point to.

I will be talking later this week with the Faculty Senate about free expression, academic freedom. I had the opportunity to do so earlier in the year. And just for us all to be thinking together about how fundamental this commitment is to who we are. It is core to our life, and we will not move away from it.

As one meaningful example, the day after Saturday, on Sunday, there were two events on Grounds, one on the Lawn and one immediately adjacent to the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, pro-Palestininan protests, as part of an event that was called "Flood the Lawn." And those were civil, peaceful demonstrations of protest in support of Palestine.

And while I didn't hear all the words, I'm sure critical of the administration, we're committed to that, and those move forward. And that, to me, over a really hard weekend, was one of there was something really hopeful and hope-reinforcing, that by the very next day we continue to be a place for civil protest and expression, expression of speech.

Kenyon?

Bonner:

Yeah, the only I'll add, I mean, that's what a university should be, a place where you can come to a community with diverse perspectives and viewpoints, different experiences, and students exercise that learning, that engagement, their voices. And you feel like this is a place where you can learn and grow. And so as we've seen throughout the academic year, students have exercised those rights.

I think that's what makes this environment rich. I think it's what makes this environment a place where people actually feel like they can learn more about themselves, others in the world. And so I hope that our students continue to do the type of activities, expressive content, programs, rallies, and demonstrations that they've done that are peaceful that provide opportunities for students to hear something that they may not agree with, but causes them and forces them to think, that they host programs and services, and perspectives, that challenges the status quo.

And they do that in the spirit of the rules and regulations we have that protect the rights of all members of our community. And so that's one of the reasons that I love working in higher education and in a public university, and look forward to continued engagement from our students and with our students on any of the issues that they believe are important.

Ryan:

Thanks.

So for those who are still listening, you should know that the entire recording of this will be posted on the on UVA's YouTube channel later today, and also appear on UVA Today.

Just some final words that I would like to share.

So I have been president for six years, and my colleagues and I have worked quite hard to build a level of trust with students, faculty, staff, and members of the broader Charlottesville community. I'm fully and painfully aware that we lost some of that trust on Saturday. And that it's very difficult to regain trust.

At the same time, I have an obligation as a president to make decisions that I think are in the best interests of the entire community, not one segment of it. And that includes making decisions that others vehemently disagree with, like deciding to leave a sign on a Lawn room door that many found offensive, but which was protected by the First Amendment. Or deciding to invite students back during COVID, which many thought was unsafe and reckless, but I thought was the safest route because most students were going to be back in Charlottesville anyway because they live off-Grounds.

Those decisions, like the ones we had to make on Saturday, are no-win situations, because some will always question them, but they have to be made. And I have always tried to make them based on principle and based on what I perceive to be the best interests of the community.

Once you make a decision, you have to own it. And you face the personal and professional consequences, which I appreciate and fully accept.

But I cannot and will not accept, though, is the suggestion I've heard from some that I don't care about students. I care about each and every one of them, including those in the protest and those arrested. I don't agree at all with the choices and the decisions that they made. But I nonetheless care about them, just like I care about every one of their colleagues and fellow students. Anyone who has been watching for the last six years would know that. And that will never change.

So thanks to my colleagues and thanks to all of you for joining us.