Former President Thomas Jefferson questioned whether he should attend the meeting of the Rockfish Gap Commission, appointed in 1818 by Virginia Gov. James P. Preston to identify a site for the newly approved University of Virginia.

Jefferson, who was advocating for the school to be located at Central College, which he was already building in Charlottesville, feared he would be a lightning rod for his opponents.

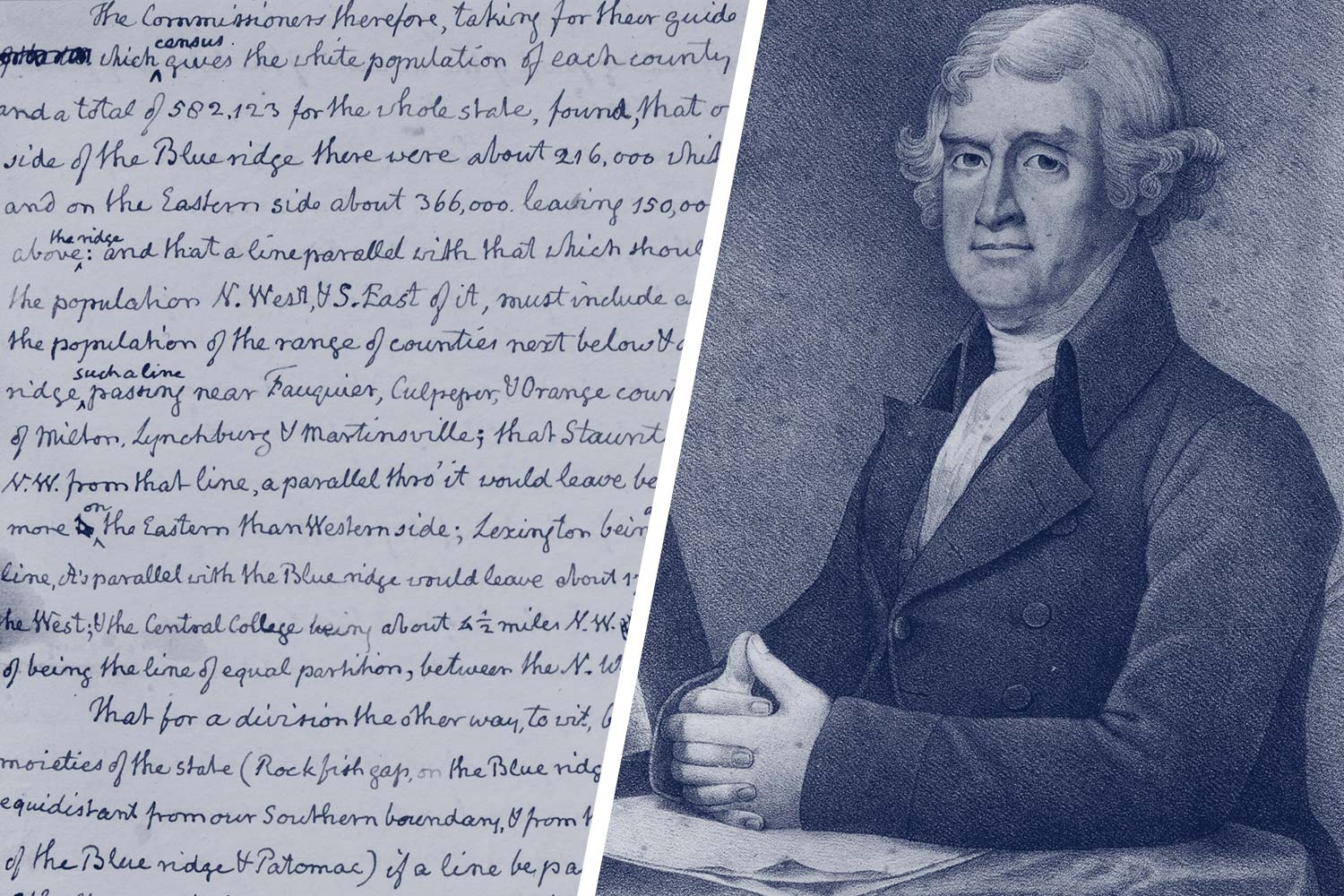

Besides, Jefferson had already written the 21-member commission’s final report before the meeting took place at the Mountaintop Inn on Aug. 1 through 4. He had stacked the commission with delegates, such as judges and local farmers, who were favorable to his position. He knew the outcome.

“It really does illustrate the exquisite political skills that Jefferson possessed,” said Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy, a faculty member of UVA’s Corcoran Department of History who is writing a book on the University’s founding. “He was always very keen to hide himself and not show his hand, so he really debated whether to go to Rockfish at all.”

Former President James Madison and state Sen. Joseph C. Cabell, Jefferson’s point man for promoting the University, convinced Jefferson to attend.

“They argued that Jefferson’s presence would help, rather than hinder,” O’Shaughnessy said. “Initially he tried to get Madison to write the Rockfish Gap report. He wanted a short draft that the commission would approve. Madison declined. I think Madison was never quite as motivated and interested in this project as Jefferson, but he certainly assisted it.”

The commission had to choose among Central College, Washington College in Lexington or the College of William & Mary, which was willing to move to Richmond. Jefferson, who argued that Central College was more centrally located for the state, knew who to lobby and how to get people to stand for various items in the legislature. He was also able to cajole Cabell to continue working on the project.

“He really used Cabell the same way he used Madison in Congress in the 1790s,” O’Shaughnessy said. “They were the front men while he stayed in the background.”

The ground for Central College had been broken the year before; two former presidents, Jefferson and Madison, and the sitting president, James Monroe, were present at the laying of the cornerstone.

“There was never any doubt that having two other presidents involved was a way to give this some prestige and publicity,” O’Shaughnessy said.

Historian Andrew J. O’Shaughnessy is working on a book about the founding of the University of Virginia. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Despite the prestige attached by a trio of presidents, there was extensive opposition to Jefferson’s plan, from some politicians based on cost and from some religious denominations based on the school’s lack of religious focus or ties.

“Jefferson was very keen that this not be one of the religious colleges and that it didn’t come under the control of the Presbyterians, a powerful group and probably the most active at the time in founding universities,” O’Shaughnessy said. “He didn’t want it to be dominated by a religious organization – that was one of the really distinguishing features of the University.”

Jefferson had been branded an atheist during the 1800 campaign and this accusation was bolstered by his insistence that there be no chapel and no department of theology at the University. But his opponents did get a concession.

“Essentially, they insisted that there be a room in the Rotunda to be used for religious worship and for different denominations to be able to set up on the perimeter of the University,” O’Shaughnessy said. “What is amusing is that he was forced to agree to this when the commissioners realized they needed to get this back to the legislature, and for it to be agreed upon and for it to become the bill for the University of Virginia.

“But once having done that, Jefferson essentially pushed back for the rest of his life. The room in the Rotunda never had a religious meeting while Jefferson was alive.”

The cost of the University project was hundreds of thousands of dollars – and Jefferson was prone to give very optimistic estimates as to what things would cost. Cabell advised Jefferson to modify his Rotunda construction estimate by $10,000 to $60,000.

“There was opposition to the cost, which was immense,” O’Shaughnessy said.

O’Shaughnessy said Jefferson’s vision for a college extended back to the American Revolution and his belief that the country needed to have an educated citizenry in a system of government by consent, plus a pool of natural leaders. In Jefferson’s vision, these leaders needed virtue, to put aside their own interests and put forward the interests of the public.

While Jefferson had been working on this for a while, it became more urgent as he aged. He feared the South was losing ground to the North; while Virginia had produced four of the first five U.S. presidents, the North had produced Harvard, Princeton and Yale universities.

“Southerners were going to places like Yale, and about a third of the students at Princeton were Southerners,” O’Shaughnessy said. “This concerned Jefferson because he felt they were coming under the control of the Presbyterians and Congregationalists – but more important, the Federalists, his opponents. And he literally regarded the views of his political opponents as heretical, alien to the pure ideology of the American Revolution. He suspected them of wanting to create an aristocracy, reestablish a monarchy and to come under Britain’s colonial influence again, without becoming formal colonies.”

O’Shaughnessy said many people assume that UVA was tasked with creating the leadership for the Confederacy, but he said this was not Jefferson’s vision.

“Jefferson was a nationalist and he thought the leadership that came out of the University, even though it did have a dominant role in the Confederate cabinet, would actually lead the nation in a purer republican direction, and steer it away from civil war. But he didn’t feel the North had any right or should it be interfering with the affairs of the South.”

From the very start, the school was Jefferson’s project.

“One of the more remarkable aspects of the story is that from the age of 71 to 83, Jefferson was working on this project in every detail,” O’Shaughnessy said. “He was designing the curriculum, the political management of getting it through, drafting the legislation, and he obviously did the architectural plans. The building was going on during the Rockfish Gap Commission; the University was already there in parts. Several of the pavilions were built, and he tried to really accelerate the plan of building, so that something very substantial had emerged by the time the commission met.”

Aside from selecting a site, the commission was tasked with determining what subjects would be taught and the selection of faculty. Jefferson had wanted 10 professors, but was willing to settle for eight; later, he hired his full 10.

“These professors were expected to teach a huge range of subjects,” O’Shaughnessy said. “There was a big emphasis on natural science. Jefferson wanted everything taught, including modern languages such as Spanish. That was quite distinctive and impressive. He also wanted students to have an open curriculum in which they could mix subjects, what was later called the smorgasbord approach to education.

“It has become a very universal feature in America, but this was really the first.”

Also unique was the vocational emphasis that Jefferson placed on education.

“This University had the first department of economics in the country and the second real medical school,” O’Shaughnessy said. “Jefferson even wanted to have tradesmen on site who would be teaching them very practical skills. It wouldn’t be part of the degree course, but he wanted some carpenters and others so they could learn very practical skills in addition to the possibility of having vocational training.”

O’Shaughnessy said the conference itself was fairly undramatic, with the commission members refining details and socializing, at the same time trying to make it look as if there had been real debate.

And while the commission worked in Jefferson’s favor, it was not a good time in his personal life. He was bankrupt and had to borrow $100 from Charlottesville merchant James Leitch just to travel to Rockfish Gap. After the conference, Jefferson traveled to Warm Springs, hoping the waters would help restore his health.

“The salutary nature of the springs would ironically be the source of a crippling staph infection acquired there that would leave Jefferson with boils on his buttocks that would torment him for a year,” said Dr. Robert Battle, co-chair of UVA’s Bicentennial Commission. “He could not ride horseback and suffered greatly on the carriage return trip to Monticello. A New York paper went so far as to falsely report Jefferson’s death. He would spend the next several months able only to write while on his stomach.”

Despite his personal suffering, Jefferson continued negotiating the byzantine politics of creating the University, and protected his vision to the end of his life.

But then things started changing. Among other things, a chapel was built on Grounds.

“What was distinctive was gradually eliminated within the University,” O’Shaughnessy said. “Part of the Rockfish Gap report was this system of having no university hierarchy, no university president. By the end of the 19th century, they had reverted to a much more traditional structure, with a university president.

“Today, the University, in terms of teaching religion, is not very different from other universities, so what was distinctive has either been copied elsewhere or has disappeared. But at the time it was a remarkable example of republican enlightenment. The University was trying to realize that from the American Revolution.”

The students were more disruptive than Jefferson anticipated on his isolated agrarian campus.

“Jefferson was imagining that there would be very academic and serious students, and that there would be sort of a monastic feel,” O’Shaughnessy said. Noting that Jefferson was tempted by the fast life while he himself had been a student at William & Mary, “He was glad that he hadn’t chosen that option,” O’Shaughnessy said. “He was very unsympathetic when he came into contact with students and he was distraught by the first riot. He famously addressed the students and cried, and he had to expel his own great nephew.”

Media Contact

Article Information

July 27, 2018

/content/200-years-ago-jefferson-left-nothing-chance-rockfish-gap-conference