When Gail Burrell Gerry applied to the University of Virginia in 1969, she had no idea they could not accept her.

Instead, her application to the University – the last all-male public flagship university in the country – was forwarded to Mary Washington College (now University of Mary Washington), which was, at the time, UVA’s women’s college. She received an offer of admission, which confused her. She went to her guidance counselor’s office in Ypsilanti, Michigan, to find out what happened and, after reading the “teeny tiny print,” they realized the University only accepted men.

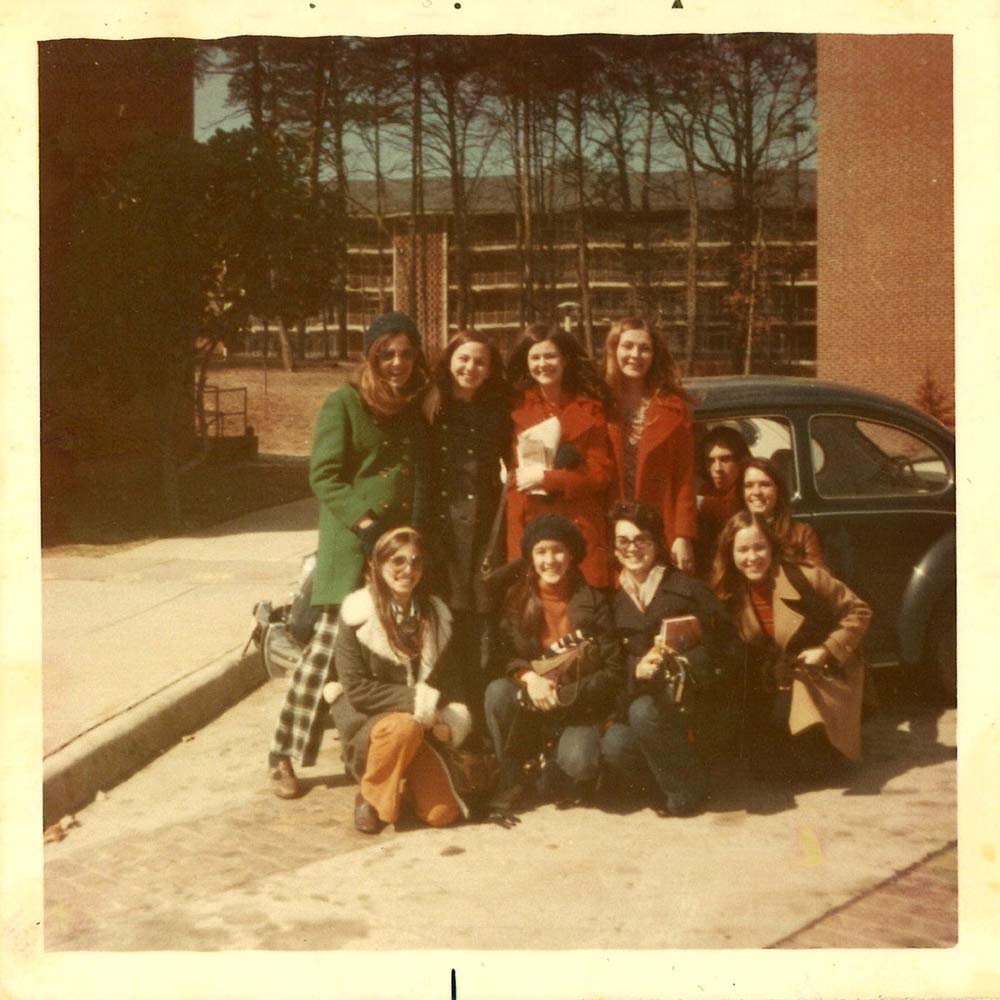

Gail Burrell Gerry poses with friends at UVA. In the early 1970s, most women at UVA did not have cars, so they traveled almost entirely on foot. (Contributed photo)

“It never occurred to me that a state school would be all male,” Gerry said.

Then, just a few weeks later, she was admitted to UVA.

Gerry became a trailblazer. Before 1970, the University did not accept undergraduate women as a matter of course. The School of Education and Human Development, then known as the Curry Memorial School of Education, began admitting women in 1920, and the student population there became majority female in 1922, according to Virginia Magazine. The School of Nursing was women-only until 1952, and some women were admitted as rare exceptions. Before coeducation, more than 30,000 women earned degrees or certificates from UVA.

John Lowe, a UVA School of Law graduate, initiated a lawsuit with the ACLU on behalf of four women in 1969 to get the University to coeducate. The Board of Visitors at first agreed to gradually increase the number of undergraduate women over a 10-year period, before relenting and voluntarily accepting full coeducation within three years on the terms Lowe’s lawsuit proposed. The women who enrolled in 1970, 350 first-year students and 100 transfer students, formed UVA’s first coeducational Class of 1974.

Gerry recently published a book, “Here To Stay: The Story of the Class of Women Who Coeducated the University of Virginia” with the University of Virginia Press, chronicling her and her female classmates’ experiences.

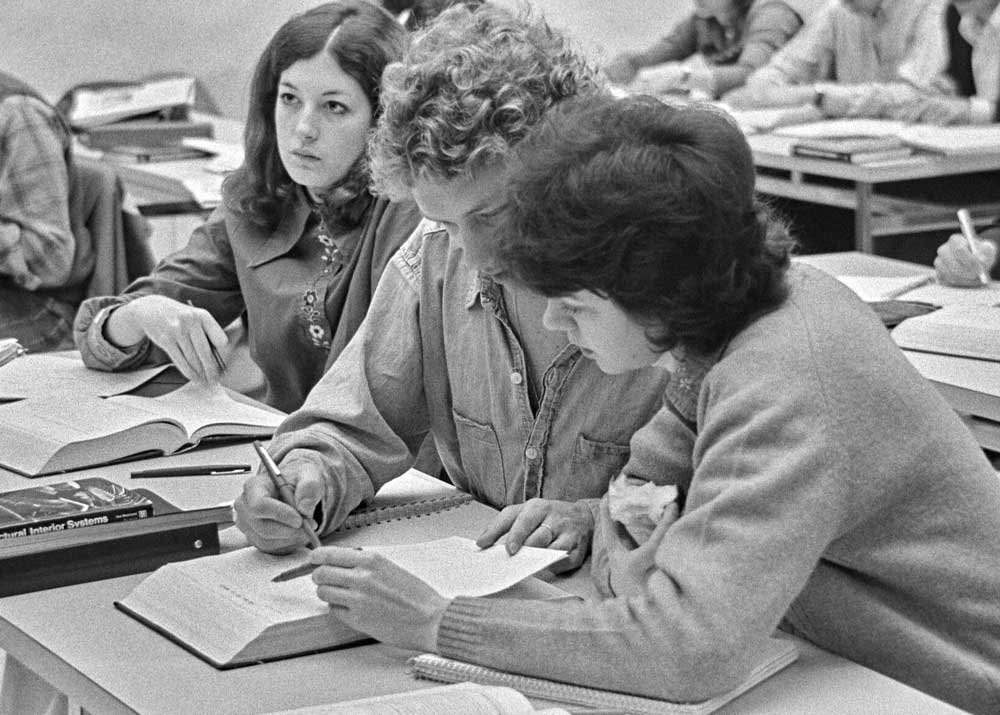

Receiving admission to the University was only the first hurdle for Gerry and her classmates. Many UVA alumni were upset over the decision to admit women and threatened to withhold financial contributions. Many senior professors felt likewise. Gerry said she was advised to avoid taking classes with more longstanding professors, who felt women didn’t have a place at UVA. The male student body was split on the issue. Some men even refused to sit next to their female classmates.

Members of the Class of 1974 say they remember their friendships with each other more than anything else about their college experience. (UVA Library photo)

Gerry took a public speaking class with her roommate. The two were the only women in the room when a classmate decided to give a speech arguing against women’s admission. He even wore a button reading “BBTOU,” or “Bring Back the Old University.”

“He gave this speech about how devastating this was for the University, how the only reason women wanted to be there was to find a husband,” Gerry said.

The men in the room smiled and cheered, she recalled. She went back to her dorm room, angry and embarrassed, and decided she had to give her own speech in response. With her roommate’s help, she concocted a plan to parody the man’s ideas.

“I came in with my glasses and my hair up and a trench coat on over some hot pants,” Gerry said. “I had undergarments that were my roommate’s, and I got up on the desk and started crawling around, saying, ‘Why would we be here if we weren’t looking for a man?’ I think the humor worked.”