It took an earthquake to convince one city to do away with a double-decker highway.

City planners in San Francisco had tried for years to get approval for removing the Embarcadero Freeway that blocked access to the San Francisco Bay, before a 1989 earthquake finally made that roadway unusable. (It also collapsed a section of another elevated highway in Oakland, killing 42 people.)

The Embarcadero Freeway was torn down, and the area developed into a waterfront park, attracting jobs, housing, activities and tourists.

University of Virginia engineering professor Leidy Klotz took his family to visit the Embarcadero park several years ago. While he didn’t know it at the time, it would become the opening story for his book, “Subtract: The Untapped Science of Less,” published a few months ago. He tells readers “subtraction is the act of getting to less, but it is not the same as doing less. In fact, getting to less often means doing, or at least thinking, more.”

It is more than worth it, his book reveals; applied to the world’s toughest problems and everyday life, the options of different kinds of subtraction are helpful and necessary as humans pursue a better future.

Klotz brings together many of the reasons why subtracting might be a more successful option or strategy and conveys them through lively stories from science, history and daily life. (Photo by Tom Cogill)

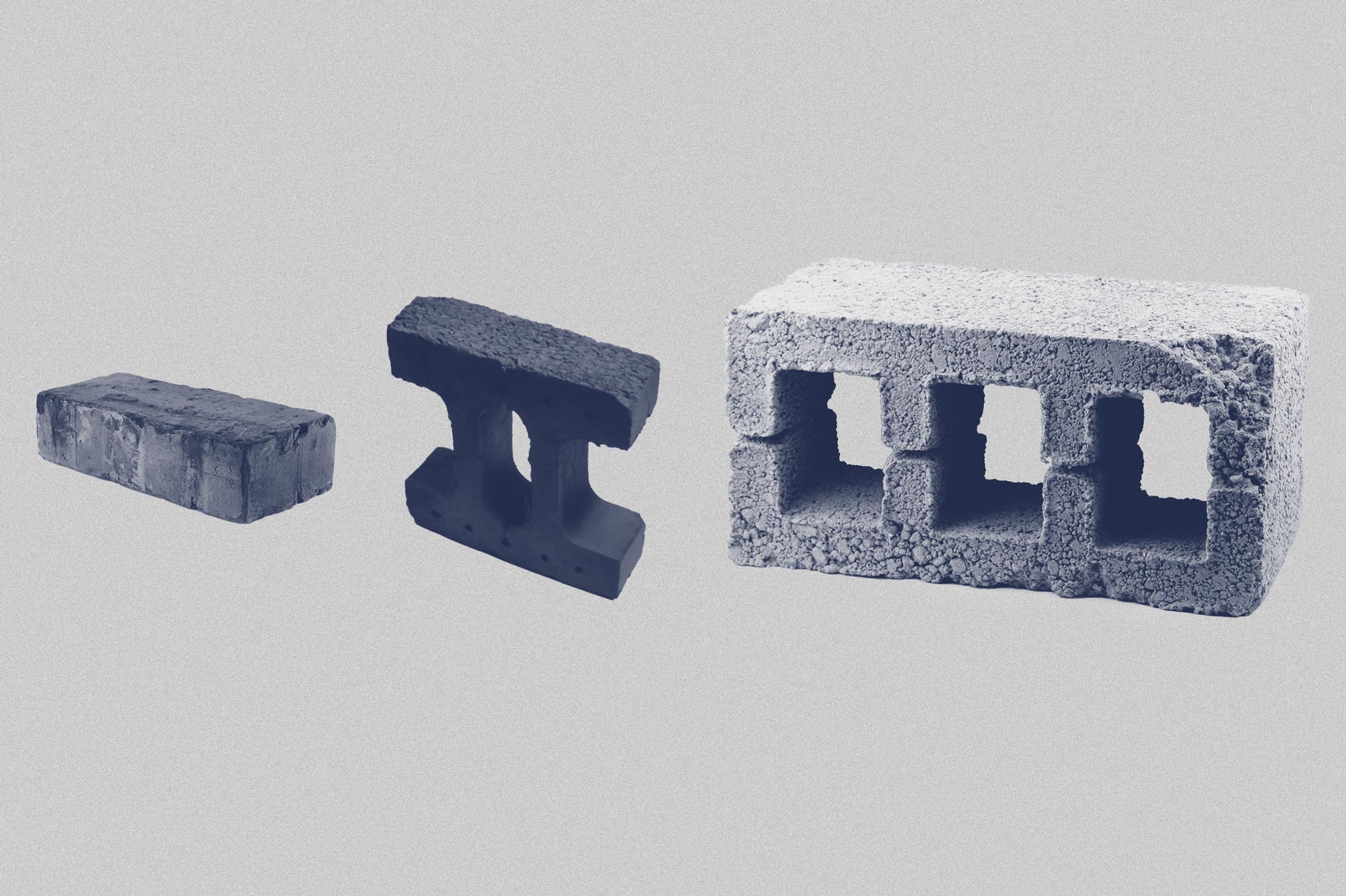

Klotz’s book has much to say about how humans came to rely on adding more, and why we should consider taking away to solve problems. To illustrate, he describes a range of ideas from concrete examples – including the invention of a new building block – to abstract concepts and dilemmas, like racism and climate change.

He brings together many of the reasons why we need to be reminded that subtracting might be a more successful option or strategy and conveys them through lively stories from his life at home – he and his son playing with Legos, for instance – to involving students in subtraction studies, to ancient history, including the early construction of temples.

Klotz, the Copenhaver Professor in the Department of Engineering Systems and the Environment in UVA’s School of Engineering, said he hopes the book will help readers “rearrange their mental furniture” to make them more likely to think about subtraction.

In addition to his own reading and research, Klotz, who also has joint appointments in the School of Architecture and Darden School of Business, worked with colleagues and students across disciplines conducting experiments to see whether people would recognize when taking away would be a better option. His collaboration with professors Gabrielle Adams and Benjamin Converse of the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy was supported by a 3Cavaliers grant and resulted in a paper published (and featured on the cover) in April in the journal Nature (covered in a previous UVA Today article), which also served as the basis for Klotz’s first chapter.

“That finding – that people systematically overlook subtractive options – raises two questions: ‘Why don’t we choose it?’ And ‘What can we do about that?’ We’re missing out on a basic way to make the world a better place,” Klotz said, adding, “How can we do better?” Considering both addition and subtraction, instead of just the former, should be the goal, he said.

Klotz said his motivation for all his work, the book included, comes from wanting to make the environment more sustainable, to allow more people to thrive, now and in the future. He had long noticed how the mindset to keep adding, thinking that “more” is always better, seemed to be a root cause of problems like climate change. His breakthrough came when he homed in on subtracting as an action. And that action, it turns out, isn’t easy.

“Removing a freeway is far more challenging than leaving it alone, or than not building it in the first place. As my team would find in our studies, mental removal requires more effort, too,” he wrote in his introduction.