In the face of accelerating and ever more complex and disruptive global challenges and technologies – from climate change to highly automated manufacturing, aerial drones or the vast proliferation of genetic engineering – can the U.S. government move beyond month-to-month crisis management to make the sort of long-term plans and policies required to meet such challenges?

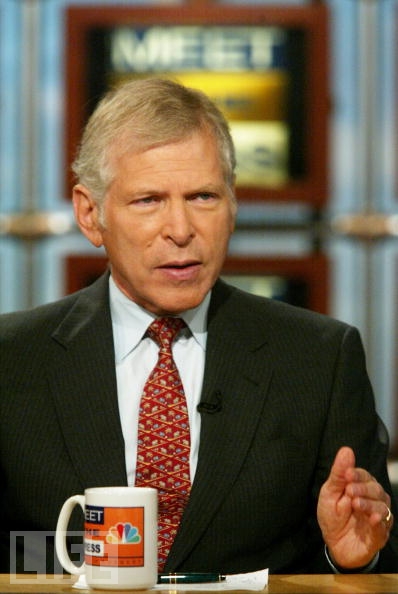

Not without substantial structural upgrades to the government’s capacity for systematic foresight and future planning, argued Leon Fuerth, former national security adviser to Vice President Al Gore, in a presentation Tuesday at the University of Virginia’s Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy.

Fuerth spoke in Garrett Hall to a graduate-level Batten School class of about 30 students on “Congress 101: Leadership Strategies,” taught by Gerald Warburg, who introduced the talk, noting that future planning “will be a central challenge of all your careers.”

Fuerth, whose government career spanned more than three decades, including 11 years as a foreign service officer, 14 years on Capitol Hill and eight years in the Clinton White House, now holds simultaneous appointments as a research professor at George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs and as a distinguished research fellow at the National Defense University.

As a capstone to his long career as a public servant, Fuerth is advocating a package of reforms and structural changes within the executive branch to equip it to better cope with the increasing speed and complexity of major challenges. The proposal, titled "Anticipatory Governance: Practical Upgrades,” published last fall, was crafted by a working group of about 30 senior officials from present and past White House administrations, and is endorsed by a who’s who of policymakers from recent administrations, including former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and former CIA Director James Woolsey as well as four former national security advisers: Sandy Berger, Zbigniew Brzezinski, Stephen Hadley and James Jones.

Fuerth first began contemplating the need for improved planning and foresight capacity while serving on Clinton’s National Security Council and National Economic Council, he said. He and then-National Security Adviser Sandy Berger noted how so many of the circumstances they encountered felt like they were being placed on a sloped game board, with war at the bottom of the board. They were constantly shuffling, reacting and working against the general slope of events to avoid war. He and Berger wondered if “something could be done earlier to shake the board” to put them on a better footing to avoid calamities.

He went on to explain how many of today’s problems are complex, rather than complicated. A complicated problem can be thought of like a machine with many parts, Fuerth said. The parts are interconnected and interdependent in understandable ways. One can take apart the pieces, tinker with one piece, then reassemble the machine and predict how it will work. One can build a model of the machine and make a confident forecast of how a stipulated change will impact the machine.

In contrast, “a complex problem is a much different animal,” he said. “There is no main driver of the system that can be identified.” All elements of the system respond almost simultaneously to change in the system. One must understand the system as a whole before one can even begin to intelligently analyze one element within the system.

With a complex system, a change of state in any part of system may lead to disproportionate or discontinuous consequences. Surprise is inevitable; error is inescapable, he said. While attempting to solve a complex problem, the system mutates. The system is always in flux so it cannot be managed to a final solution.

The human body is a complex system, so it cannot be well understood by a 19th-century approach like dissection, which kills the system and renders it static in order to study it. To fully understand the human body, it must be studied while alive.

Similarly, the U.S. government was designed on the very best organizational principles of the early 19th century: hierarchical, segmented, mechanical and sluggish, Fuerth said. “This is no longer our world. Our 19th-century government is simply not built for the nature of 21st-century challenges.

“On both sides of the aisle, one finds commitment to preconceived ideas of causality and consequence,” he said. “Complexity theory holds that both are very dangerous and will blow up in your face.”

As one example, he cited the George W. Bush administration’s refusal to plan for what might happen after Saddam Hussein’s overthrow if the Iraqi people did not manage to very quickly create a well-functioning Western-style democracy.

“Policymaking will benefit from the insights of complexity theory,” Fuerth said. “Can a democratic government respond to today’s faster rate of change? The rest of the world is watching to see, and many watching have no attachment to the ideal of democracy.”

“At Batten we are trying to teach over-the-horizon thinking, and how to ask the unasked question,” Warburg said. “These are the skills our students will need to be the policy advocates of the future.”

The talk was especially relevant to public policy students said Alan Safferson, a fifth-year in Batten’s five-year accelerated Bachelor of Arts/Master of Public Policy program. “In the future we will have to face these more complex problems and to understand them.”

Media Contact

Article Information

November 1, 2013

/content/4government-must-upgrade-its-planning-capacity-batten-school-visitor-argues