Growing up on Virginia’s Eastern Shore with an interest in coastal science, Cora Ann Baird was unaware she was living so close to a leading research center focused on her home’s coastline.

Decades later, she helps run it.

The University of Virginia’s Coastal Research Center in Oyster hosts the Virginia Coast Reserve Long-Term Ecological Research project that began in the mid-1980s, about the time Baird was born. She is now the research center’s site director.

Environmental sciences professors Karen McGlathery and Max Castorani lead the VCR LTER program, which investigates the ecological impacts of the world’s largest seagrass restoration effort. It has brought back vast undersea meadows that disappeared nearly a century ago. The team works to understand how the re-emergence of seagrass – successfully restored across almost 14 square miles – shapes the coastal bay ecosystems and the organisms that live there, including many fish and shellfish species.

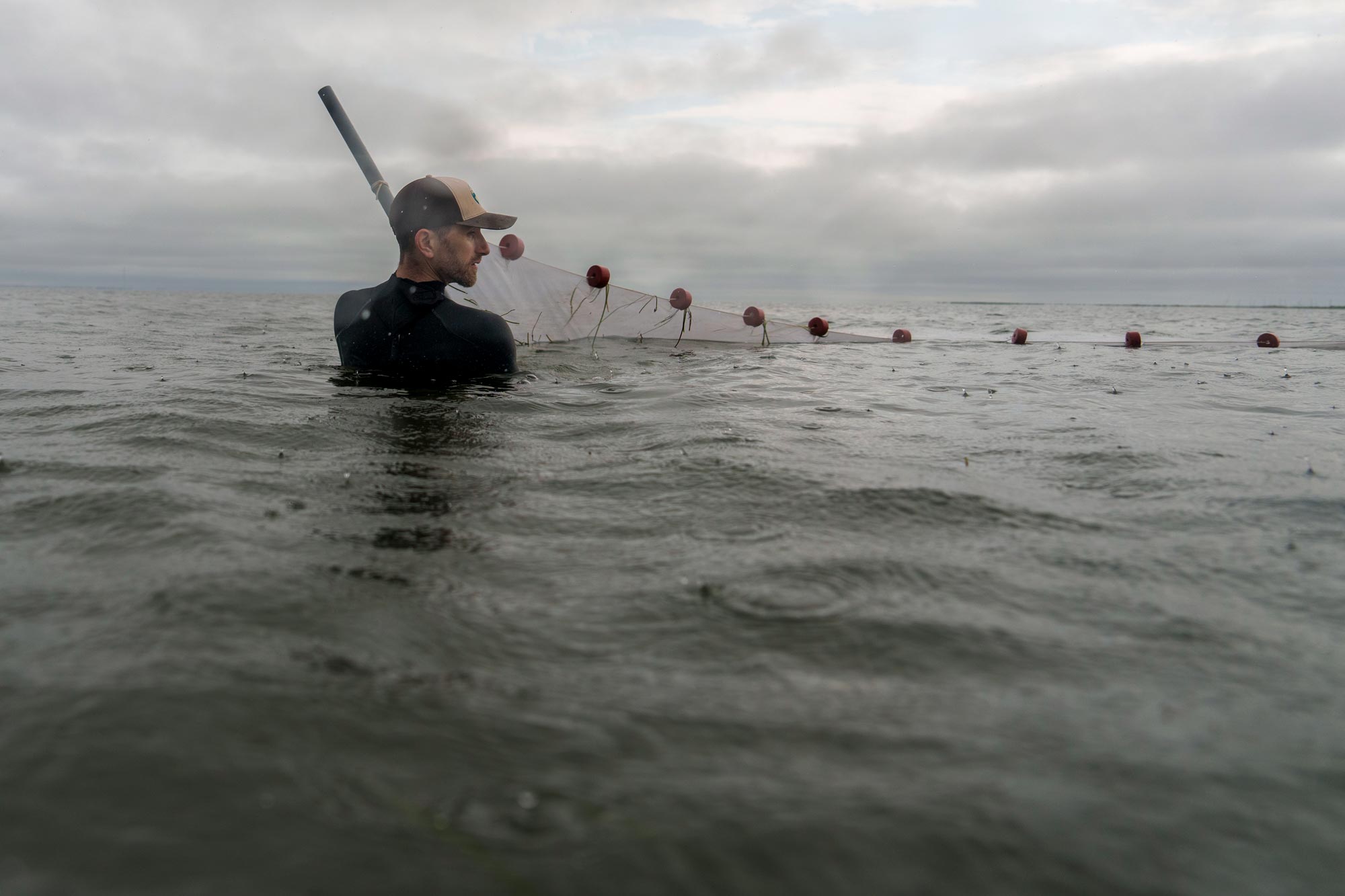

Researchers’ nets commonly catch small fish, including anchovies, sea bass and, occasionally, seahorses. (Photo by Lathan Goumas, University Communications)

“Seagrass was very abundant in the coastal bays between the barrier islands and the mainland for decades, probably for centuries, until the 1930s, when the seagrass became locally extinct because of disease,” Baird said. “So, there’s an entire generation or two that doesn’t remember seagrass being out here.”

In the late 1990s, a few observant watermen noticed a bit of seagrass and alerted the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, where researchers were already working on restoring seagrass in the Chesapeake Bay – kickstarting a collaborative effort among UVA, VIMS and The Nature Conservancy to accelerate its recovery.

For nearly 40 years, the National Science Foundation has funded the VCR LTER project to study the ecology of Virginia's coastal bays – among 26 projects comprising the Long-Term Ecological Research program. Decades of research have allowed scientists to establish baseline data, so they can determine when changes are happening in the ecosystem and predict future trends, according to Baird.

Max Castorani, associate professor of environmental sciences, leads students in studying oysters and the keys to their survival and restoration off the Virginia coast. (Photo by Lathan Goumas, University Communications)

“Out here, there’s so much less human influence, so when we start to see patterns, it’s much easier to attribute them to regional and global phenomena,” Baird said. “Without as much local input, it’s easier to see the big picture.”

Since 2012, the research team has tracked how seagrass restoration affects fish in the region. They catch, measure and release fish that live in the seagrass to assess the effects of restoration and environmental change. Each June, the team samples the meadows, pulling large nets across the water and counting the fish they find.

In addition to generating new discoveries, the research creates training opportunities for students at UVA and beyond. This year, UVA environmental sciences doctoral candidate Luke Groff is helping out.