Paulette Jones Morant came to the University of Virginia to get an education. Her plans did not include sports.

“I have a name for myself,” said Morant, whose maiden name is Jones. “I am ‘The Accidental Athlete.’”

A graduate of Norfolk Catholic High School, Morant arrived on Grounds in August 1970 as part of UVA’s first class of undergraduate women. Even if she had been interested, intercollegiate athletics were not then an option for women at the University. But that would change.

By the time Morant graduated in 1974 with a bachelor’s degree in Spanish, the field hockey and women’s basketball club teams had attained varsity status at UVA, and she’d had a hand in each.

As a girl growing up in Norfolk, she enjoyed baseball, which remains one of her passions. “Basketball was not in my aura,” Morant recalled, “and field hockey definitely was not.”

Leading the drive for women’s sports at Virginia were graduate students who’d competed in athletics at other schools, Morant said.

“They said, ‘Women at UVA need something to do, and we’re gonna organize some clubs,’ ” Morant said. “The first one they organized was the field hockey club. I just happened to be walking down the street. If I been on the wrong side of the street, none of this would have happened.”

Morant, then a second-year student, “saw a friend who said, ‘Hey, we’re going to a field hockey club meeting. We’re going to join the group and form a club and somebody from New Zealand is going to be in it and she’s going to tell us all about field hockey.’ I said, ‘I actually hate that game. I don’t get it. But I do want to meet this kid from New Zealand, so I’ll come with you.’”

At the meeting, Morant discussed her aversion to the sport with a graduate student who was organizing the club, “and she said, ‘Oh, I can make you like it.’ I went, ‘All right, I want to see you do it.’ ”

And so began her career as a field hockey player.

“I learned some skills,” Morant said, “and then eventually, my fourth year, we became an intercollegiate team [in 1973]. Now, my skills still were not wonderful, but they were OK, and field hockey was a great experience.”

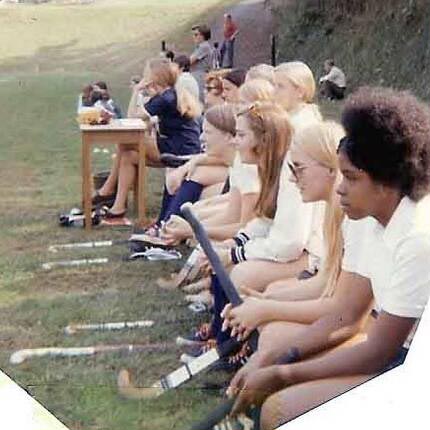

Paulette Jones Morant grew to enjoy field hockey during her time at UVA. (Contributed photo)

When the club’s first season ended in the fall of 1971, a group of women at UVA decided a women’s basketball club was needed, too.

“And of course they looked at me and said, ‘Paulette, what position do you play?’ ” said Morant, who stands 5-foot-9. “And I said, ‘Zero. None. I can’t play it.’ They said, ‘That’s OK. You’re the most organized person we know. Would you please be manager?’ ”

So began her affiliation with women’s basketball at UVA. She managed the club in her second and third years. In her fourth year, 1973-74, women’s basketball became a varsity sport at the University, and Morant had a heavy course load that forced her to relinquish her manager duties.

“A friend of mine stayed as manager,” she said, “and then some younger women took over as managers, but at least I was able to see both sports go from club to team status. I was glad I was on the ground floor.”

She was also one of the first female DJs at the WTJU radio station, along with her friend Vivian Lerner. They hosted a classical music show that ran for 3½ years, Morant said.

Growing up in Norfolk, Morant attended Catholic schools. When UVA announced that it would become fully coeducational, starting in 1970-71, her mother encouraged her to apply. Morant wasn’t enthusiastic about the idea initially, but she ended up applying and was accepted.

Other first-year students who enrolled at UVA in 1970 included Wyatt Andrews and Larry Sabato, who’d been her classmates at Norfolk Catholic, too. Andrews, now a UVA professor, is a retired national correspondent for CBS News. Sabato, a longtime University professor, is the founder and director of UVA’s Center for Politics.

“One word I associated with Paulette right from the time I met her in 1966 was ‘dignity,’” Sabato said. “No white person could begin to understand how difficult it was for a Black child to survive and prosper in the racial hothouse of those times. But Paulette did prosper, drawing on her remarkable maturity and intelligence. We could all see that she was someone special who would overcome any obstacles placed in her way.”

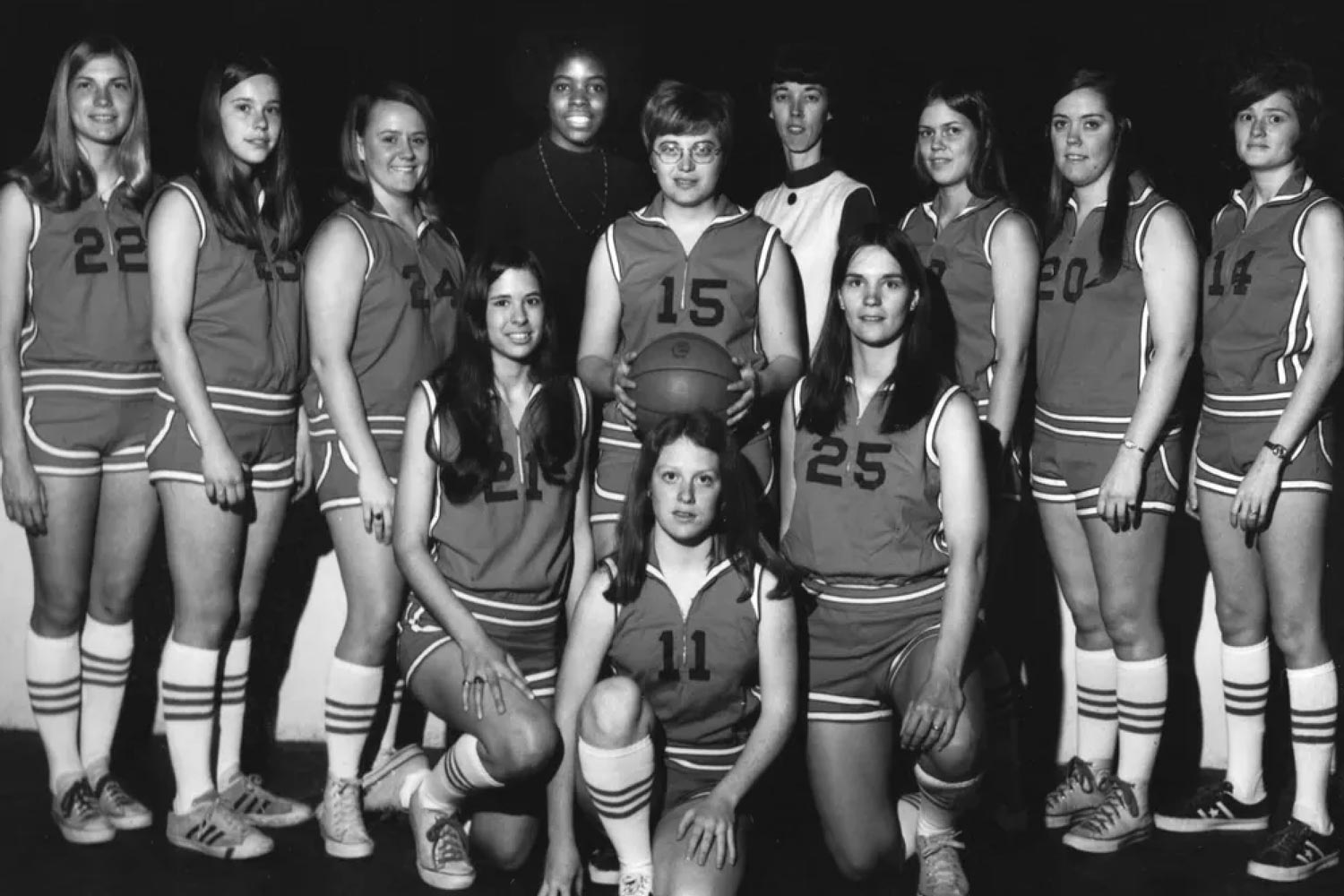

As a second- and third-year student, Paulette Jones Morant managed the fledgling women’s basketball club. (Contributed photo)

Morant said there were about 300 women in UVA’s Class of 1974, plus about 100 women in the Class of ’73 who’d enrolled as transfers.

African-American students were a distinct minority in the UVA student body then, Morant said, and for some it was their first time in an integrated school.

“Imagine that pressure of feeling, ‘I’m at UVA, and this is my first experience with integration. I am probably the first one in my family to go to college. What should I do?’ ” Morant said.

Her first-year class included about 90 Black students, Morant said, and that group suffered considerable attrition, for various reasons, in the years that followed.