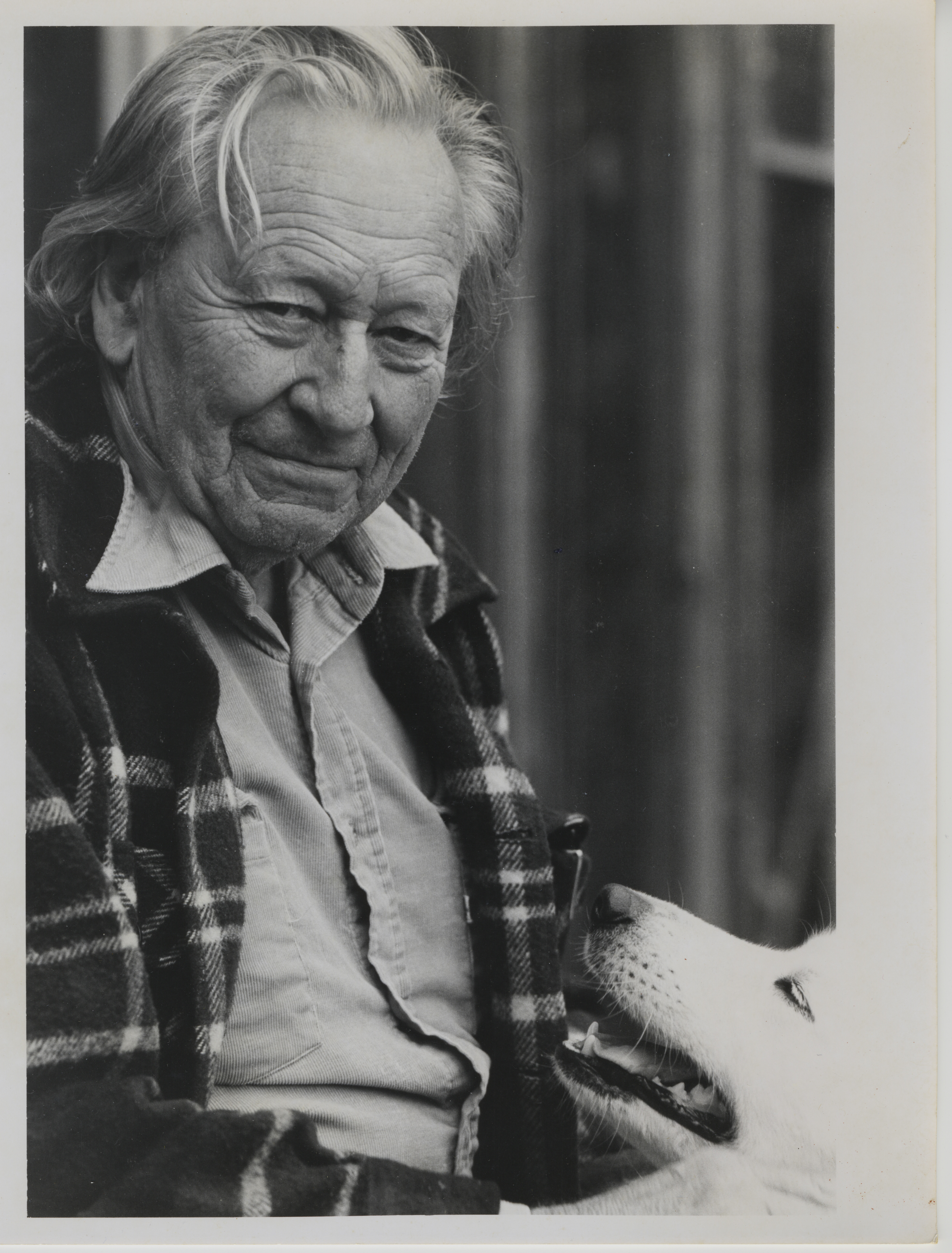

Who was the late Gregory Bateson? Anthropologist, ecologist, evolutionary biologist, psychologist, philosopher, systems theorist, family man, poetry lover – the range of his research, activities and ideas make it hard to pin him down, said Ira Bashkow, associate professor of anthropology in the University of Virginia’s College of Arts & Sciences.

Bashkow helped organize a symposium April 10-12 on Bateson with Stephen Nachmanovitch, a musician, author, educator and former student of Bateson’s who lives in Charlottesville; and Bateson’s daughter, Nora Bateson, who recently produced an award-winning documentary about her father, “An Ecology of Mind.” Her film, screened April 11 at Vinegar Hill Theater as part of the symposium, sold out in advance.

The film takes its name from one of Bateson’s groundbreaking books, “Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology,” first published in 1972. His wide-ranging work spanned from the 1930s to his death in 1980.

“That he worked in so many disciplines was a consequence of his way of thinking,” Fritjof Capra, Austrian physicist and author of the best-selling book, “The Tao of Physics,” says in the film. “He was not interested in specializing in a narrow field. He was interested in larger patterns. He was interested in how things are connected and especially how living things were connected.”

From ecology and evolution to poetry and storytelling, participants from a variety of academic disciplines gathered April 12 in Brooks Hall for a discussion-in-the-round on Bateson, who is often credited with helping to inspire the modern ecology movement with his ideas about the interconnectedness of human beings with the natural environment. The 10 panelists, including Bashkow, Bateson and Nachmanovitch, sat in the circular rows among the audience rather than apart from it, as an experiment in encouraging everyone to be part of the discussion.

Manuel Lerdau, a professor of environmental sciences and biology at U.Va., said evolutionary biologists are still discussing and dependent upon Bateson’s work from 50 years ago. Bateson, whose biologist father coined the term “genetics,” looked at the environmental pressures that push organisms to change, including different ranges of time. The seasons influence plants to change, for example, but longer periods in the history of Earth cause different kinds of changes, Lerdau said.

“Organisms are not just made up of hierarchical levels of organization, but they are also interacting systems,” he said.

Bateson borrowed economic models to explain evolution and applied anthropological ideas to policy, seeking to understand how human and natural structures change and adapt. He believed there is no such thing as objectivity.

For instance, when Bateson studied tribes in New Guinea and Bali, he looked for the relatedness in what they took for granted in their culture and daily life. He wrote about rituals from several points of view, not just anthropologic observations. He applied what he learned there in subsequent research on schizophrenics and alcoholics at a veterans’ hospital in California, and in seeking to understand family dynamics.

One of his main principles, Nachmanovitch said, was there are always feedback loops, because everything is interconnected. That’s a problem for human beings, as we try to “fix” things or be responsible, whether in the environment or in a family. There’s frequently a double bind – another term of Bateson’s – in which an individual, group or system receives two or more conflicting messages, so that responding to one cancels the other out, but it’s not simply a “no-win” situation. The people involved might not be conscious of what is being imposed on them.

A simple example: a person in a position of authority imposes two contradictory conditions on a subordinate, but there is an unspoken rule that one must never question authority. What does the underling do? Sometimes nothing but keep quiet; sometimes it’s possible to find a creative solution, participants pointed out.

“The context and the application of knowledge matter,” said Sandy Seidel, U.Va. assistant dean and associate professor of biology.

In evolution, it’s understood that every decision or action has a cost that can’t be avoided, Lerdau said. Natural systems interact without thinking about the consequences. Even if humans try to avoid negative results, they can’t control everything.

We often fail to take all the variables into account, said Phillip Guddemi, president of the Bateson Idea Group and another student of Bateson’s. He used the problems afflicting honeybees as an example. Several things have been identified as reducing their numbers, but no one takes them all into account in developing solutions to keep the bees from extinction.

“Humor is a way to get at the double bind,” offered Katie King, another former student of Bateson’s and professor of women’s studies at the University of Maryland, College Park.

Bateson, and his daughter, Nora, used the croquet scene in Lewis Carroll’s “Alice in Wonderland,” where all the pieces are living, moving objects, to illustrate humans’ lack of control of the systems of which they are part.

Nora stressed the importance of remaining open to learning. In the film, she showed how her father was constantly, continuously exposing his children to the natural world around them. He also studied animals – especially dolphins, chimpanzees and sea otters – and looked at how they engaged in play, to look at the levels of communication.

U.Va. psychology professor Angeline Lillard, who studies child development, said that adults play “pretend” with babies as young as 7 months old. “How do babies know what’s real and what’s not?” she asked. They must have at least two levels of understanding – or what could be called “meta-communication” – going on at the same time, she said.

Other human endeavors that involve “meta-communication” are poetry and art, which English professor Herbert “Chip” Tucker discussed, using one stanza of a poem by John Keats, “Ode to a Grecian Urn,” as an example. He talked about the poet’s use of language, rhyme and meter that create a feedback relationship between the art and science of its construction.

Poems illustrate Bateson’s ideas intimately and repeatedly, Tucker said. “Art is a system of meta-systems.”

Bateson continued to be curious and optimistic, Bashkow and others pointed out, even though his writing could come across as dense and abstract. It was always connected to some physical piece of data or object.

Bateson says in the film: “We are beginning to play with ideas of ecology, and although we immediately trivialize these ideas into commerce or politics, there is at least an impulse still in the human breast to unify and thereby sanctify the total natural world, of which we are.”

Media Contact

Article Information

April 18, 2013

/content/bateson-s-ideas-about-interconnectedness-relevant-ever-today