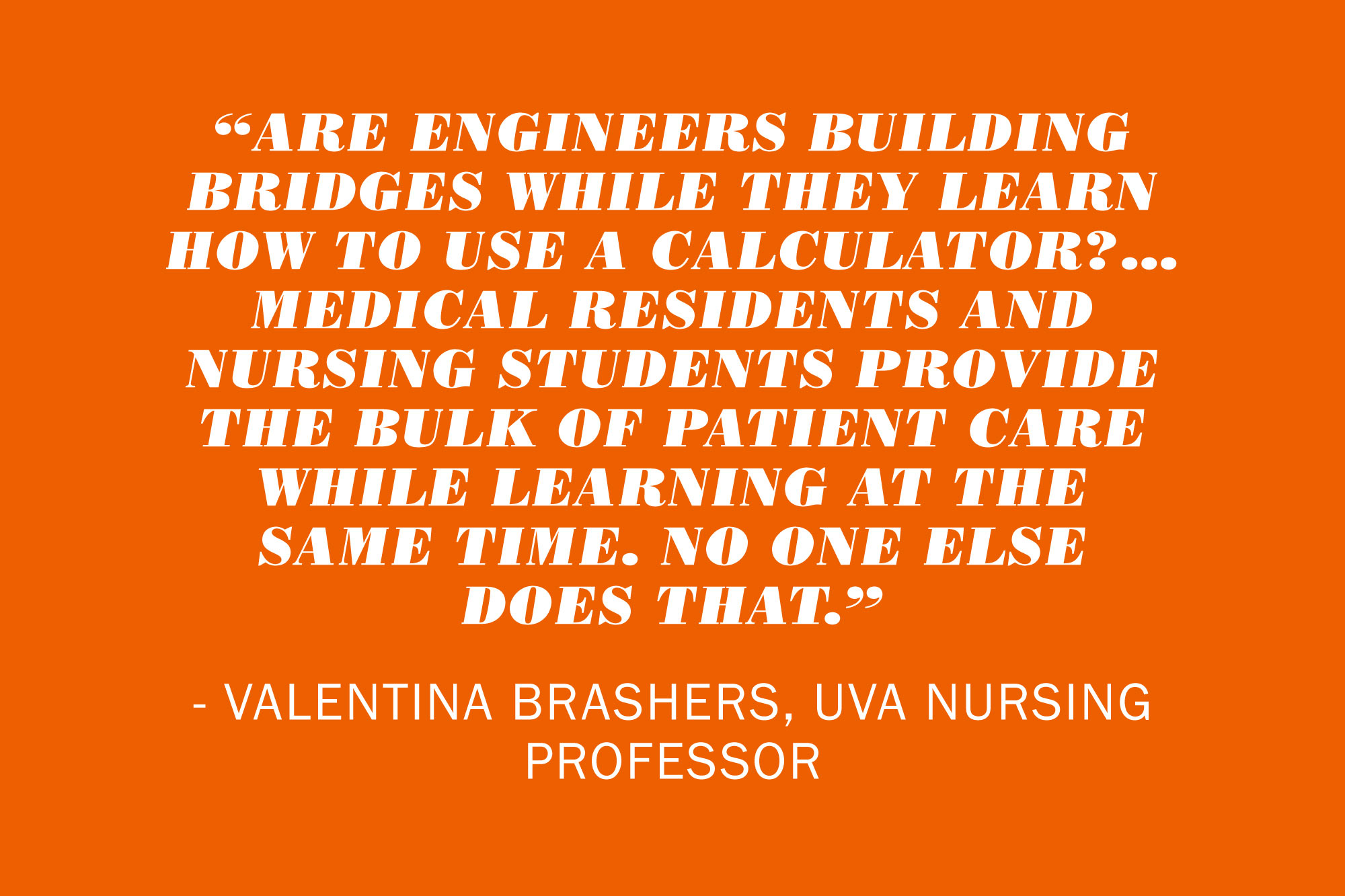

Valentina Brashers calls it the “poof” factor.

“Poof,” and a doctor’s directives are invisibly, deftly done. “Poof,” and the IV line, catheter, blood draw and medication are promptly administered. “Poof,” and nurses sweep in, do whatever the heck they do and everyone moves on.

Clean, efficient, separate. Boom.

But on her first full day as a young physician, Brashers – overflowing with knowledge of pulmonology and asthma’s disease process – couldn’t administer an IV drip because the clinic’s nurse had gone home. And “poof,” an idea was born.

UVA was ahead of the curve in fostering interprofessional education, in which future doctors and nurses learn side-by-side.

“Many of the things that nurses and nursing students do for patients had been invisible to me,” recalled Brashers, a University of Virginia nursing professor since 1987, an attending physician and founder of the Center for Academic Strategic Partnerships for Interprofessional Research and Education, or ASPIRE, UVA’s interprofessional education hub. “I realized I had very little knowledge about what nurses were trained to do. I also realized that there was real value to a team approach.”

At the outset, Brashers’ logic was simple: Establish multiple required opportunities for medical students to learn basic patient care skills from veteran nurses, emergency medical technicians and respiratory therapists in an interprofessional learning environment. But what happened since the concept’s infancy has been nothing short of a revolution in nursing and medical education, with UVA leading the charge.

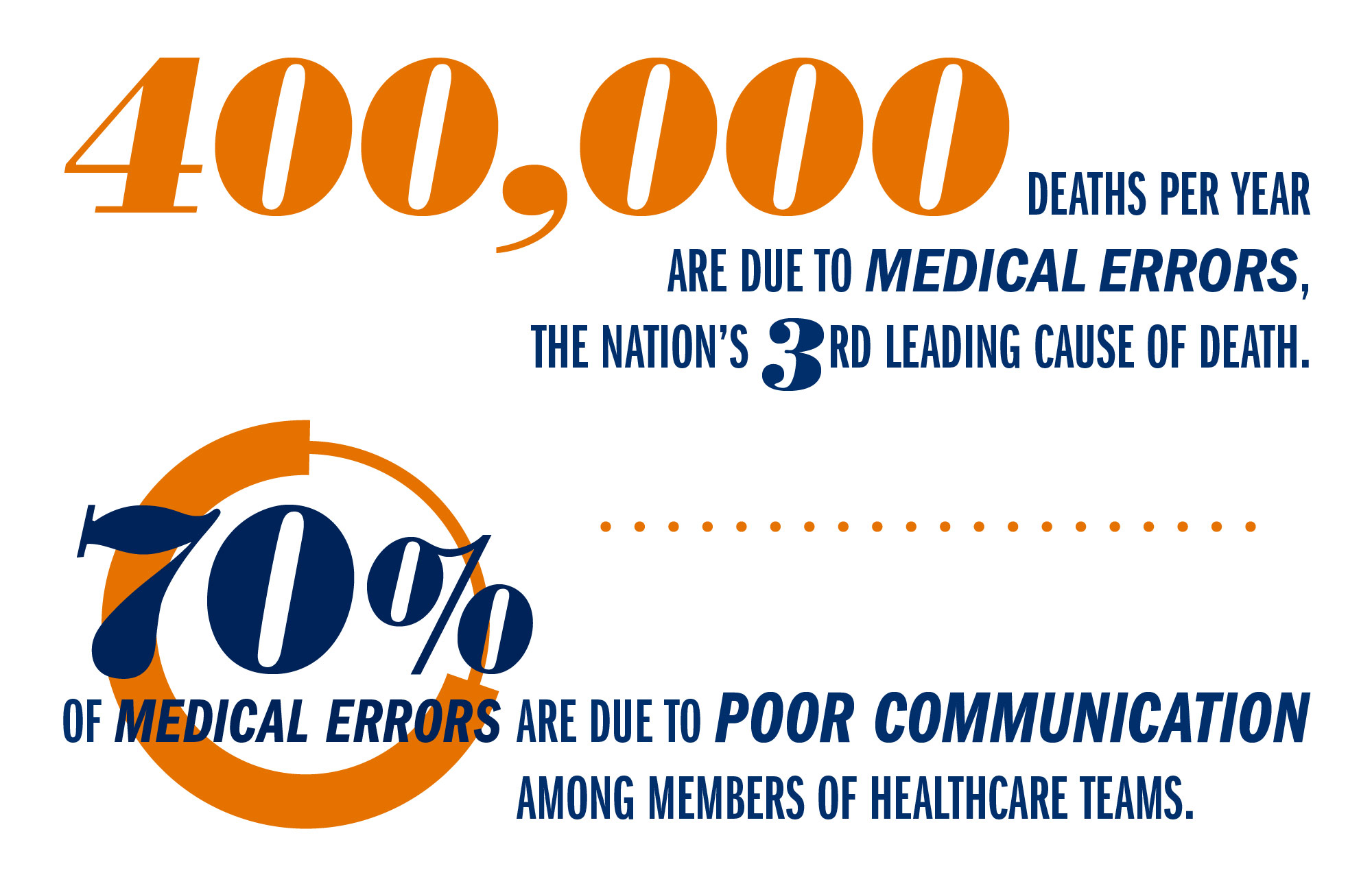

Pack Leader

Although interprofessional education began at UVA in the early 1990s – more than a decade before its explosion in academia in the mid-aughts – the concept goes back much further. Even in the 1960s, the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) had recognized IPE as a key to efficiency in patient care. But with its 1999 report, “To Err Is Human” – the first to identify communication gaps as a major cause of medical errors – IPE earned its rightful place as a driver of safety, too. Four years later, the Institute of Medicine’s Health Professions Education report documented the need for a “collaboration-ready workforce,” bringing a growing chorus of support from academic governing bodies like the American Association of Colleges of Nursing and the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Though laudable, early IPE mandates were also foggy. How, exactly, do you teach clinicians to be sound collaborators? How do you know whether you’re successful? And once a spirit and practice of cohesive collaboration exists, how do you measure and strengthen it?

Thanks to Brashers’ early advocacy, UVA worked ahead of the IPE curve through much of the 1990s, even with its spotty and decentralized approach. This was when UVA medical students received basic training from nursing instructors, and nursing students regularly interacted with pharmacists, respiratory therapists, chaplains and physicians. But even by the early 2000s, nursing and medical students rarely crossed paths.

It wasn’t until School of Nursing Dean Dorrie Fontaine’s 2008 arrival that goals crystallized: Create regular, required courses in which nursing and medical students learn in the same space and from one another. Formally establish IPE as a curricular thread in both schools. Create a rubric to measure interprofessional competencies. And ask nursing and medical faculty members to integrate IPE into their courses.

“We went from doing IPE as a side interest to a major role,” Brashers recalled with a laugh, “almost overnight.”

By 2011, IPE flavored both the nursing and medical schools at UVA. Together, nursing and medical students discussed provocative case studies and practiced end-of- life conversations. They convened for patient simulations and study related to medication adherence, emergency responses, difficult discussions and transitions in care. In Jeffersonian style, they dined while discussing one another’s roles and perspectives.

A $750,000 grant from the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation in 2011 was followed by the 2013 establishment of the Center for ASPIRE, a joint venture between UVA’s schools of Nursing and Medicine and its Health Sciences Library. In 2014, a grant of more than $1 million from the Health Resources and Services Administration further expanded the effort. Today, IPE is as common as the white coats clinicians wear.

Measure Twice

IPE’s surge is concurrent with its painstaking measurement. That process begins by creating a checklist of the hoped-for behaviors critical for the simulated scenario at hand: Did the participants introduce themselves? Ask open-ended questions? Listen thoughtfully?

The scenarios are then acted out, tested and tweaked. Once the simulations are cemented, students are assessed in real time by observers watching for specific skills. Even the actors themselves – from UVA’s bank of “standardized patients” – grade the students.

The resulting metrics reveal profound before-and-afters. In one two-year study of 457 UVA nursing and medical students exposed to interprofessional simulations, students’ collaboration skills improved by more than a third. Graders noted a near-50 percent improvement in measurable indicators of teamwork. And nearly 100 percent of students “strongly agreed” that the workshop helped them see the value of teams in providing safe and effective patient care.

“Some medical students told us they always wanted to work with nursing students because it more realistically simulates what happens,” Brashers said. “Others called the exercises a ‘bridge over barriers.’”

Today, student-led initiatives like the HeArt of Medicine course – a workshop in which nursing and medical students practice end-of-life conversations with simulations involving dying patients and their families – round out a plethora of formal and informal interprofessional offerings for students to practice and learn together. Simulations offer potent practice time with immediate feedback, preparing them for the infinite variety of real people and situations yet to be encountered during clinical rotations and clerkships.

And students aren’t the only ones benefiting. Twice-a-year, “Train-the-Trainer” faculty development programs bring together dozens of professors, clinicians and administrators from within and outside UVA looking to establish, amplify and assess their own IPE programs. Activities drive home lessons in a fun, informative way, like the LegoBot Challenge, originally developed by two University of Cincinnati psychologists, in which teams are timed to assemble a brick figure using one person’s observations and ability to convey details. Other training activities include the “Room of Errors,” in which doctors and nurses have seven minutes to identify pre-planted errors in a mock hospital room, independently at first and then collaboratively, to accentuate the value gained by multiple perspectives. In the “bad behavior BINGO” game, participants observe a video of clinical situations and categorize actors’ skills on a game card.

But make no mistake: the work underlying IPE is stone-cold serious. And its promise, UVA researchers say, whittles costs, begets shorter hospital stays, reduces staff burnout and attrition, minimizes mistakes and decreases the wastefulness of unnecessary procedures.

“At its heart, a lack of interprofessional competency is actually an ethical breach,” Brashers said. “Teamwork improves care. The data is so overwhelming that to not practice as a team is actually unethical.”

A Door, Propped

UVA graduates who’ve had the benefit of interprofessional learning say its lessons stick.

As a medical intern, Pranay Sinha, a 2014 graduate of the School of Medicine, and his peers often sought refuge in a private workroom set aside for physicians, accessible only by card swipe. The barrier left nurses peeking through the glass and knocking feverishly when needing to discuss a patient – a situation Sinha, now a resident at Yale New Haven Hospital, called “insane.”

When, instead, he propped the door with a trashcan, face-to-face interaction among nurses and physicians on the unit improved and phone pages declined precipitously. And while the solution’s simplicity belies its effect, Sinha said the idea “arose out of all those IPE courses.”

“Once you’ve been in an interprofessional atmosphere,” Sinha said, “you’re surprised by how the traditional structure of medicine works against the natural collaboration of nurses and physicians.”

A stinging early encounter with a frazzled medical resident formed the approach Katelyn Rybicki, who holds two UVA nursing degrees, took to her practice. A nurse in UVA’s Medical Intensive Care Unit, Rybicki – one of Brashers’ first teaching assistants and now a Doctor of Nursing Practice student – continues to instruct beginning medical students in basic skills, and said negative encounters can get “the wheels turning about IPE.” Training under Brashers, she said, “really shaped my early perspectives [of] figuring out others’ roles and [viewing] my own role as being as important as others.’”

We all – doctors, nurses and others – have the skills to contribute to the care and success of the patient, Rybicki added.

Others said IPE’s lessons broaden their practice perimeters. That was true when the caregiver of an elderly patient of 2016 Doctor of Nursing Practice alumna Alex Wolf recently collapsed into exhausted tears. Wolf sought counsel from his hospital’s chaplain, not to hand off the issue but to see “what [he himself] could do to support the patient moving forward” by getting advice. To Wolf, it’s one of IPE’s biggest takeaways.

“I’ve worked on teams where everybody thinks everyone else is great, but then they divvy the pieces of patient care separately, rather than working on them together,” said Wolf, a palliative care nurse practitioner at Augusta Health in Fishersville. “Sometimes that’s appropriate, but a big part of being on a great team is being able to learn from your colleagues and act on their recommendations.”

Among IPE’s greatest champions are those who are urging forward its study and momentum.

Tara Albrecht – one of Brashers’ early disciples and among the first students to experience UVA’s more integrated approach to IPE as she earned three nursing degrees – said the interprofessional approach she learned at UVA runs deep, and “touches every aspect of my career.”

“My time at UVA made me realize, when I wasn’t even a nurse yet, how we each come from a slightly different view, and how, working together, we can really help the whole person,” she said.

Old Hands, New Ideas

Today, IPE continues to expand, even in what will shortly be the post-Brashers era, as the venerable professor plans for her imminent retirement. And although IPE is nothing new to Dr. John Dent and Beth Quatrara, ASPIRE’s new clinical directors, they, with faculty members Dr. Julie Haizlip and John Owen, are laying novel groundwork for the center’s next act.

Dr. Tina Brashers, right, has influenced the collaborative practices of a generation of UVA doctors and nurses, including B.S.N. graduate Susan Murphy, left. Brashers will retire this summer.

A lot is in the pipeline. Haizlip is developing a burnout survey with UVA’s Darden School of Business and considering a phalanx of online IPE tools and tutorials. Quatrara is creating a smattering of new simulations focused on patient handoffs. Owen is making plans to expand ASPIRE’s off-Grounds reach and establishing new models for IPE “short courses.”

Dent, for his part, is planning to spread a new way to conduct “rounds,” the regular patient assessments that inform care plans. “Rounding with Heart” involves roving groups of clinicians – social workers, pharmacists, physical therapists, doctors and nurses – who enter a patient’s room en masse to discuss the plan of care with the patient. Concerns are aired, questions answered. With a visible and cohesive team, care plans are crystal clear.

Sound revolutionary? It actually is. On the UVA Medical Center’s 4 East floor, where the novel practice has become routine, attrition is the lowest across the entire hospital.

“We used to have the highest turnover, and now we’ve got the absolute lowest,” said Dent, who adds that patient satisfaction on the Rounding with Heart unit has reached new highs. “That’s a direct result of our interprofessional approach.”

And with UVA graduates taking IPE on the road, its future is bright.

Medical School graduate Chelsea Becker Hutchinson, now a general surgery resident at the University of North Carolina, knows to use colored (not white) towels for patients upset by body fluid stains. She realizes that sitting with a patient to grieve is as important as explaining a prognosis. And she is fully aware that colleagues – especially nurses – inspire some of the best ways to care.

“It’s incredibly valuable, having someone else’s perspective,” Hutchinson said.

Albrecht today is a nursing professor at Virginia Commonwealth University and an oncology and palliative care nurse practitioner at VCU Medical Center in Richmond. “I can’t even imagine how I’d practice without my interdisciplinary team. For me, IPE is as ingrained, as vital, as a stethoscope.”

Sinha agrees: “The larger point to me is that we need to give one another the benefit of the doubt,” he said. “I think I have more perspective about what it’s like to be a nurse, and that really helps me not project my frustrations, and to make nurses my allies. Which they absolutely are.”

Media Contact

Article Information

June 5, 2017

/content/better-together-three-decades-team-approach-improves-patient-care