Christina Reifsteck held it together – until she saw the shoes.

They were old. They were small. They were shoes a child or a toddler might wear, scattered among piles of adult-sized footwear men and women once wore.

That’s when it hit her. The enormity of human brutality and cruelty slammed square into her heart, the heart of a mother of two teens.

“I’m sitting in Birkenau by the railroad track, and I’m just feeling the tears welling up, and I’m not wanting to have this full-on crying session,” said Reifsteck, a deputy chief of police with the Rantoul Police Department in Illinois, just north of Champaign-Urbana. “Another woman, who was also a mother and whose children are much younger than mine, said, ‘That one hurt.’ And it did.”

Reifsteck joined more than 60 police officers from the U.S. and Europe who traveled to Poland. She went to learn as part of a University of Virginia School of Continuing and Professional Studies course, Policing in Nazi Germany: Leadership, Genocide and Contemporary Applications. Students also took part in the International March of the Living to Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II-Birkenau, infamous World War II-era Nazi concentration and extermination camps.

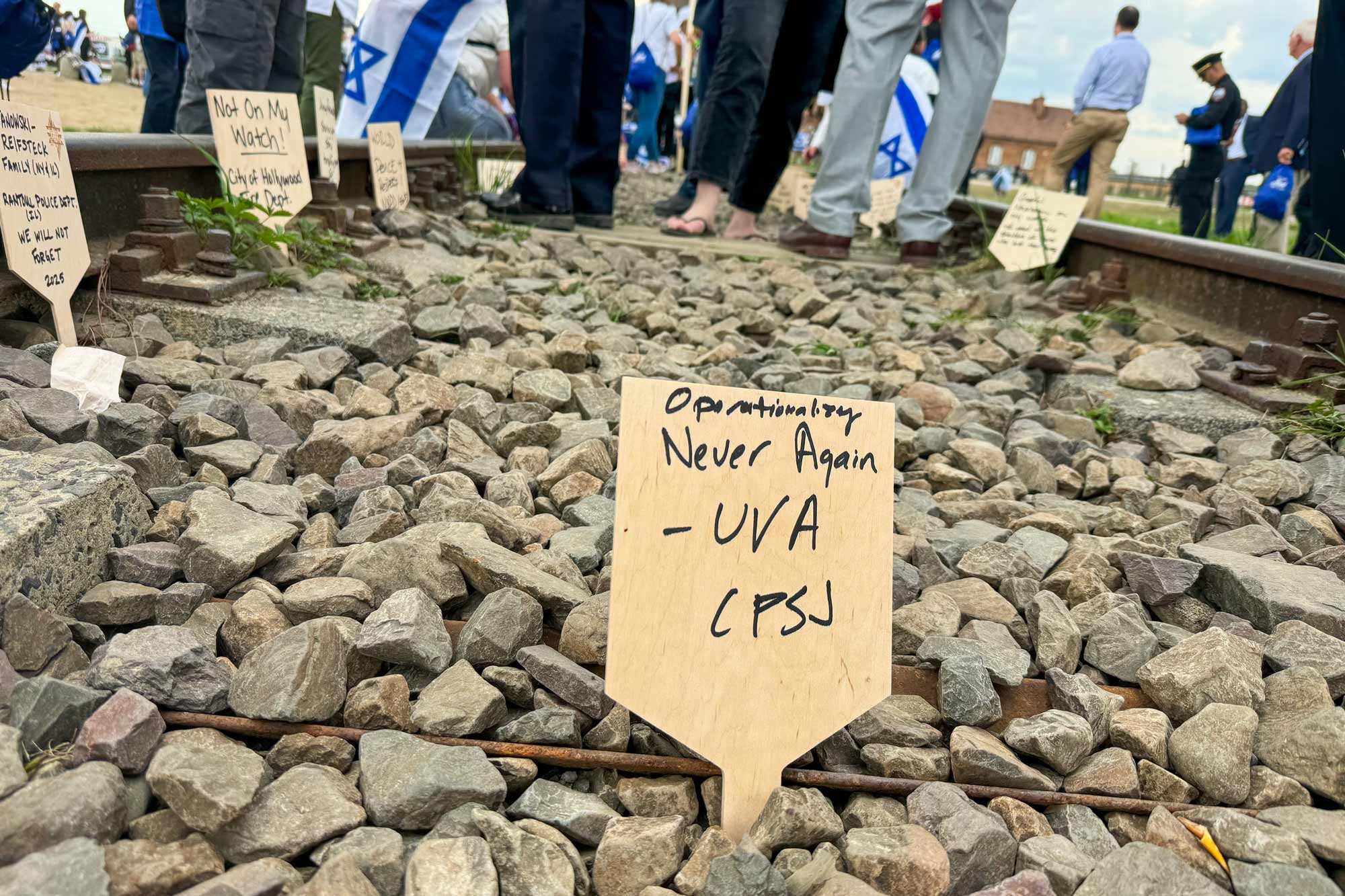

The course is part of the school’s Master of Public Safety program. With its unofficial subtitle, “Operationalizing ‘Never Again,’” the course aims to help law enforcement leaders understand how local police contributed to the roundup, deportation and mass murder of Polish Jews and others in the Holocaust.

Small placards line the railroad tracks leading to World War II labor and death camps Auschwitz and Birkenau, expressing thoughts, prayers and pledges to prevent genocide from happening again. (Contributed photo)

“The coursework focused on police leadership and police battalions during the Holocaust period and their role in active bystandership,” Reifsteck explained. “Basically, they just stood by or even participated in the killing of millions of Jewish and non-Jewish people. Even if they felt it was wrong, they never spoke up.”

Reifsteck has earned her degree from the School of Continuing and Professional Studies’ Master of Public Safety program. She’s also been accepted at the FBI Academy. She has made policework her career, and knows it involves weighing conflicting interests of individuals and of society.

“I felt somewhat sympathetic to these police battalions, because I don’t think they were allowed to have a voice during that era,” she said, noting the Nazi regime’s hold on the region and its blatant and violent disregard for human rights. “They also cared about themselves and their family, and they knew what was happening to others could easily happen to them. The questions we have to ask are, ‘What could they have done?’ and ‘What would we do?’”

It’s a question she’s asked many times since the tour.

“It really strikes you when you’re walking around (the Krakow Jewish ghetto) and see where they lived, see the bullet holes still in the walls of the buildings that they have purposely kept there, see the walls that were used in the Jewish ghetto to block them from being seen or seeing out and keep them contained,” she said. “I think about it. And then I ask myself in the current professional setting, how can I make sure we’re not doing those things now? Do we have a metaphorical wall? How can we break that barrier?”

As educational as the trip was for Reifsteck, it was personal, too. Of Polish ancestry, she arrived a week before the class with her aunt to research her family history.

.jpg)