Instead, many do partial truckloads and so truckers combine businesses and optimize their routes accordingly. For the last four to five years, we have seen trucker shortages, mostly from retirements in the older workforce and not enough young people entering the workforce. With the pandemic, when everything shut down, a lot of people were let go, and many small operators shut completely down. These jobs have been traditionally lower-wage jobs with long hours, and to fill the worker shortages, truckers are now competing with all the other sectors and industries that are facing a staff shortage, including school buses and restaurants.

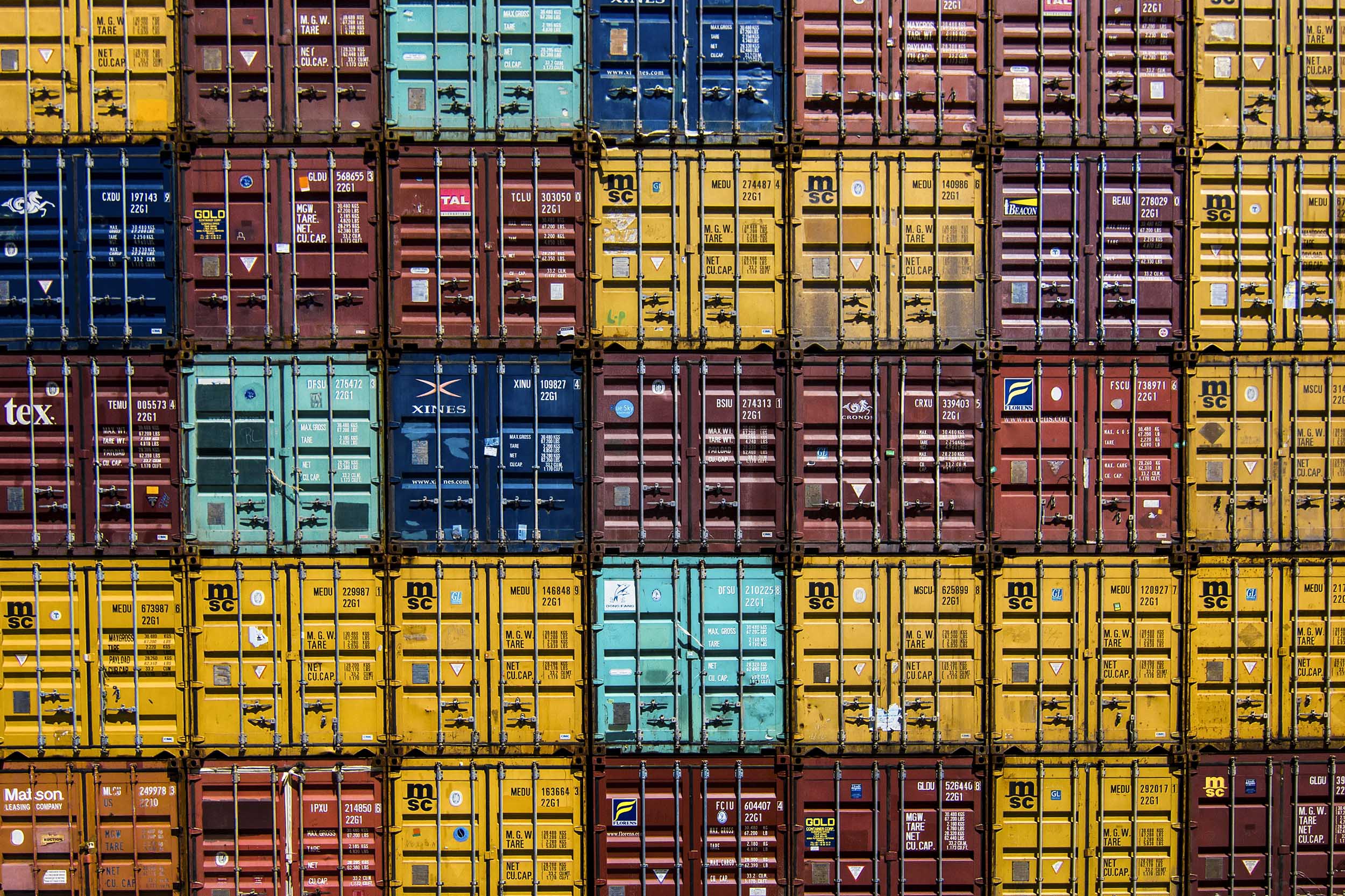

When small risks at the early stage like worker shortages at ports and ships, reduced capacity in carriers and containers that can cross over from ships to rails/trucks etc. happen across multiple points in the supply chain and remain for an extended period time, it becomes a big crisis for the economy as a whole with goods piled up at ports and empty shelves in stores. Unlike a store operation, it is not easy to add capacity here. Setting up a trucking operation takes time; you need the right vehicles and skilled drivers. What we are seeing right now is the big operators adding as many workers as they can to their existing capacity.

On the other end, holiday season has typically been a season of shortages, especially for retail. Holiday sales make up almost 40% of the year’s sales and every year we see expedited shipments and missed deadlines.

This time round, the demand uptick came early. Once vaccinated, people felt safe enough to spend again. We are seeing close to 150% increase in demand and still less than 70% of supply; this mismatch is bound to exacerbate the effect of the trucker shortages.

Q. Has anything surprised you during the course of this crisis, either in what has occurred or how the situation is trying to be rectified?

A. If we take a step back and look at how supply chains have evolved over the years, much of this could be anticipated. Many businesses do not have good visibility into their own supply chains, let alone the sector and global supply chains. Many of the risk strategies currently in place allow for managing operations when a factory is shut down for a few days, events that have a 20% to 30% impact on demand or supply. They are not set up for a complete loss in supply for an extended period and have no visibility to the interconnections. All global supply chains transit through eight to nine major routes that were already operating at 90%-plus capacity. When all the demand made its way back to the supply sources and then onto the ships, should we be surprised at the multiple points of backlog?

I have to say that I am surprised at the mismatch between consumer expectations and reality. We are very attuned to our immediate surroundings. Eighteen months back, when everything shut down, we were patient with shortages and deliveries because we saw it around us and there was fear in the hearts and minds about the future. Today, we see everything open and goods are available at the click of a button on the internet. When they don’t arrive, we are frustrated and surprised. But we don’t see the global supply chain behind these products, understand the lead time and capacity issues.

Q. If you had a magic wand, how would you attempt to resolve the situation?

A. I would want to pare down the number of options on the consumer side (would you have really wanted a purple handbag if you only had primary color options?) to manageable demand sizes and on the supply side, add capacity where there are bottlenecks in the global supply chain, not just within our borders. If you look at the policy responses (bringing the military in U.K., asking 24/7 port operations in the U.S.), they alleviate local bottlenecks. But none of these are of much use for the power crisis that happened in China and shut the factories down for better part of a week, further squeezing supply.

On the brighter side, I have been surprised at the innovation this crisis has brought on from small entrepreneurs. For instance, there is a hotline setup for DIY Halloween costumes. There were secondary packaging solutions when restaurants were shut down. Much of the services sector pivoted to remote operations and we continued to buy and sell houses, educate our children, and carry on life for most part. This innovation spirit would bode well anytime a crisis hits us again.

Q. Overall, how much do you think this crisis is hampering world economic recovery amid the pandemic?

A. It is a significant impediment to recovery. What we don’t see are the hidden costs. If components don’t get delivered, products cannot be made, no sales happen and, no cash comes in for the next set of operations, and so on. In the end, it will be the small businesses that are dependent on a global supply chain, and consequently the people running and working in them that will suffer most.

One of the reasons we keep hearing of a big divide is that the unskilled worker pool does not have the opportunity to yet participate in the recovery. The shortages we are seeing are widespread in the low-wage sector, and for many potential workers, the risk is not worth the stress and wage. If the recovery is hampered, this segment will get further driven away from mainstream and further strain the recovery.

Q. Does it matter if you’re a small business or big business right now? Or is the impact all the same?

A. The shortages have not spared anyone. If you are a big business, it probably seems much more in scope. But small businesses operate on very tight working capital. The impact on them will be felt much more if they are not able to maintain the cash flow to keep the operations running. On the other hand, many small businesses that operate in the services or even local manufacturing sectors may not see as much as an impact. I would be cautious extrapolating this to “buy all local,” though. When it comes to minerals, cotton, etc., these are global resources and we are dependent on a global supply chain.

Q. Have you discussed the crisis or used it as a teaching point with students in your courses? Does it tie in or affect any new research?

A. Almost every class! I teach core supply chain in the residential MBA program where we teach “managing variability” with inventory and capacity buffers. We start with a case on the N-95 mask shortages early on in the pandemic, so this is very front and center in the classroom. I teach an elective on “Sustainable Global Value Chains.” How global supply chains are structured, where do we see pinch points, what are the major risks – these get covered in great detail in the elective, for both EMBA and the MBA programs.

I wrote a case “Food Supply and COVID 19: Breaking the Chain.” Eighteen months on, we still have a food supply chain crisis going on, and some of the reasons still remain. I teach both parts of this case in the MBA/EMBA programs and in Exec Ed. It brings home the immediate and long-term effects of this crisis.

As part of my research, I work on the risk of counterfeit parts and illicit flows in the electronic supply chains. This research deals with the problem of counterfeit parts that we see in our HVAC systems, aircrafts and many other systems. One of the main pathways of entry is purchase on the internet, and this happens where there are widespread shortages at the authorized distributors. The current chip shortage aligns with this research where we are seeing increasing reports of counterfeit chips as a result of the shortage.

Q. Is there anything else you’d like to add?

A. We do need to work our way out of the crisis right now. But once things come back to normal, we need to take a good hard look at our consumption patterns and the supply chains that support it. Are they sustainable? It would be easy to brush this crisis off as a once-in-a-100-year event and go back to things as before. That’s not going to be the case. We have seen many of these once-in-a-100-year events happen every few months (Texas freeze, New York rains, California fires).

The crisis is forcing us to take note of our supply chains and we can no longer claim ignorance. If things continue as normal, we are in for a few more of these in the next decade. I think we each have to work toward sustainable global supply chains. Whether we know it or not, just by being a consumer, we are each part of this chain.