John C. Jeffries Jr. holds a special place in the history of the University of Virginia School of Law. A star student, professor, dean and adviser to the president of the University, the 1973 UVA Law graduate played a critical role in securing the school’s financial future and setting the stage for its continued success.

This school year, he is reaching a milestone few have achieved: 50 years as a faculty member.

Jeffries has had many full-circle moments in his decades at UVA Law. He attended the school at the tail end of the Vietnam War and witnessed other world crises; he clerked for a U.S. Supreme Court justice and later hosted members of the high court as dean of the Law School; and he welcomed class after class of students, some of whom later followed his path and joined UVA Law’s faculty.

Current Dean Leslie Kendrick, a 2006 Law School graduate, called Jeffries “a Law School treasure.”

“John could have spent the last 50 years as a leader in any number of fields – public service, private practice, business – anywhere in the nation,” she said. “It is our good fortune that, of all the places he could have devoted his incredible talents, he chose here.”

To hear Jeffries tell it, he would not trade his experiences for anything. Whether serving as dean or professor, he said, “I liked everything about it.”

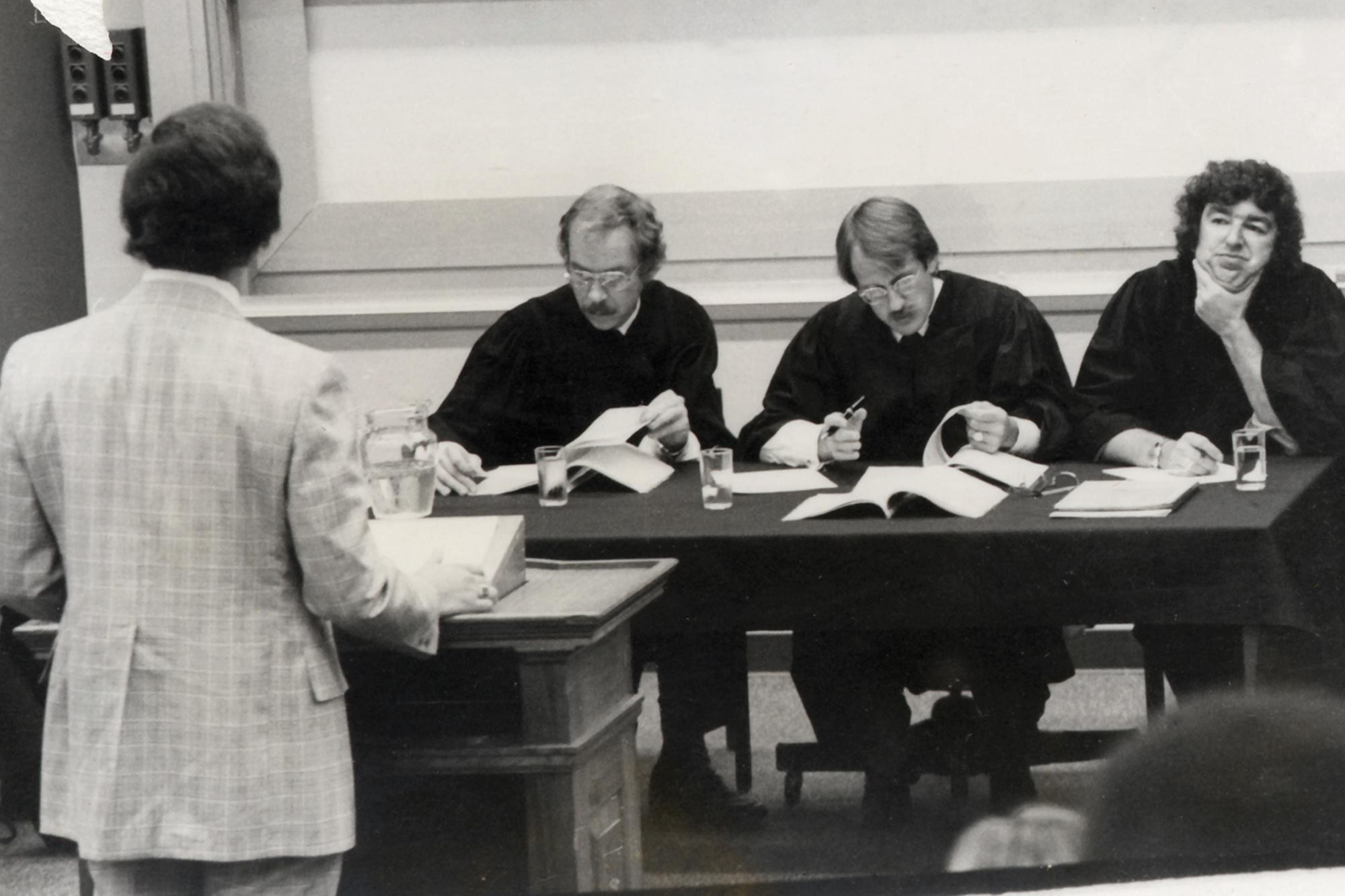

Professor Michael P. Dooley joins Jeffries and professor Peter W. Low in judging the William Minor Lile Moot Court quarterfinals in October 1975. (Photo courtesy UVA Law Archive)

Happy Accidents

Jeffries’ journey at UVA started with a scholarship offer from then-Law School Dean Emerson Spies. During his senior year at Yale University, Jeffries’ draft lottery number was called. Going to law school allowed him to join the Army as an officer, as long as he began ROTC training at Yale.

“I was willing to serve, but unwilling to serve as an enlisted man. I was too much of a snob,” he said. (Jeffries has also had five decades to master the art of the bon mot.)

He entered a law school fundamentally changed by Vietnam. Students were older and “overwhelmingly male” compared to today, he said.

“Most of the guys whom I went to school with had either served in the military or done something to avoid serving in the military,” Jeffries said.

Professor emeritus Peter W. Low, a 1963 UVA Law graduate who eventually served as UVA’s provost from 1994 to 2001, taught Jeffries in his Federal Courts course.

“He was well-known among the faculty as one of the stars of his class,” Low said.

Although it may have looked like teaching could be in his future, Jeffries said joining the faculty was essentially “an accident.”

After law school, he clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr., whom he would later memorialize in a biography. It was unusual to go straight into a Supreme Court clerkship, but Jeffries had a supporter in another Powell clerk, 1972 Law School graduate J. Harvie Wilkinson III, who encouraged the justice to hire his friend, and who later became a “feeder judge” to many Supreme Court justices. After spending a day with Jeffries, Powell told the third-year law student he would hire him “if it could be arranged,” which meant, Jeffries eventually realized, that it would be arranged despite his military service obligation.

After his clerkship, he started training in the Medical Service Corps as a second lieutenant.

“When I was there, Vietnam collapsed,” he said. “So they said, ‘How many of you would like to go home?’ And I raised my hand.”

That was November 1974. His former professor, Walter Wadlington, told him, “‘We have a place (on the faculty). Why don’t you come here?’”

“So I did. I thought I would stay two years,” Jeffries said.

Jeffries hosts Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist during festivities celebrating the school’s 175th anniversary in October 2001. (Photo courtesy UVA Law Archive)

On the Path to the Deanship

“I’ve always been treated well by students, from the first day till the last day I taught,” Jeffries said. “My impression is students respect you if you care about them learning. If you are invested in their education, invested in their understanding of the law, they appreciate that.”

Having steered away from classes in finance – “If I understood money, I might have some,” he noted – he was drawn to public law, teaching a blend of constitutional law, federal courts and civil rights litigation courses.

Along with good judgment, his colleagues and students praise Jeffries’ legal analysis.

“You feel like you’re in the presence of the most rigorous, most insightful legal mind around,” professor Kenneth S. Abraham, who has known Jeffries since 1983, said. “I don’t think I’ve ever been around someone who has a finer legal mind than John Jeffries.”

He succeeded Robert E. Scott as dean in 2001, serving until 2008.

Soon after Jeffries assumed the deanship, the Sept. 11 attacks rocked the school and the country. Televisions were wheeled into common areas so the community could follow the coverage. The next day, they gathered in Caplin Pavilion.

“John was the one who spoke, commiserated, held us together, inspired us to go forward,” Abraham said. “That was John’s leadership.”

What faculty and staff don’t see, Abraham said, is that every dean commits various “quiet acts of courage” almost every day.

“They have to do something that takes a lot of courage, and it gets no publicity,” he said. “Sometimes nobody ever hears about it. Well, there was a lot of that from John.”

The ‘Greatest Story in Legal Education’

One of Jeffries’ first charges as dean was to finish something his predecessors Scott and Thomas Jackson started: establishing what came to be called “financial self-sufficiency.”

Amid declining state financial support, Jeffries said the Law School faced two challenges – the University claimed a varying portion of its tuition revenue, and its below-market tuition stressed the school’s limited resources.

Through Jeffries’ new financial self-sufficiency agreement, the Law School gave the University 10% of tuition revenue, gave up state funds and gained more control over tuition rates.

“That was certainly one of the most important events in the history of the Law School,” Abraham said. “Jackson began it. Scott carried it forward, but John was able to get the treaty signed.”

To counter concerns about tuition hikes for graduates wanting to pursue public service or practice in rural Virginia, the school adopted what Jeffries called “the country’s most generous loan forgiveness program.”

“It’s the most generous because most loan forgiveness programs say you work in public service for five years, and we forgive your loans. We forgave year one in year one, year two in year two,” he said. “As soon as your obligation to pay arose, we forgave it if you were in public service.”

The current plan repays the loans of graduates earning less than $100,000 annually.

In May 2018, Jeffries participates in a Law Alumni Weekend panel with fellow former deans Robert E. Scott, Thomas Jackson and Paul G. Mahoney, and then-Dean Risa Goluboff. (Photo by Tom Cogill)

Jeffries also credited Board of Visitors members Gordon F. Rainey Jr. (a 1967 Law School alumnus) and Leonard Sandridge, then UVA’s executive vice president and chief operating officer, for building support for the plan among BOV members and the state legislature. Law School Foundation President and CEO Luis Alvarez Jr., a 1988 UVA Law graduate, said financial self-sufficiency “changed the trajectory of the Law School.”

“He had the trust of the University and the Board of Visitors, but every deal needs an architect to succeed,” Alvarez said. “John turned the math into a narrative about the Law School’s future … It is the greatest story in legal education of this century.”

Jeffries has a strong belief in succession planning, something he said corporations focus on and “universities don’t.”

“There are times when you need to go outside (for a candidate), but in general, you ought to be training people to take over,” he said. He pointed to Jim Ryan’s tenure as academic associate dean at the Law School. The 1992 UVA Law graduate went on to lead the Harvard Graduate School of Education, serving as an important step on his path to becoming UVA’s president in 2018.

“I thought it was important for (former UVA Law Dean) Paul Mahoney to have experience. I thought it was important for Jim Ryan to have experience, because it was easy for me to foresee that they were natural leaders, and they should have training. That’s what Bob Scott did for me. And it’s what (Dean) Risa Goluboff did for Leslie Kendrick.”

When Ryan became UVA’s president, he recruited Jeffries to serve in a new role: senior vice president for advancement.

While Jeffries explained he made changes “that required some political clout,” he handed the reins back to current Senior Vice President for External Relations Mark Luellen when he left three years later.

Ryan said he has “never known anyone quite like John.”

“He is brilliant, an incredibly gifted teacher, incomparably eloquent, has a wicked sense of humor, and is one of the most loyal friends one could ever have,” Ryan said. “There’s an old-fashioned quality to John as well, in the very best sense of that term. He cares deeply about his friends, his family and the University of Virginia, and he has been an exemplary leader and teacher at the University. I feel beyond fortunate to know him and call him a friend, even if every visitor to Madison Hall, when they see John, assumes he is the president of UVA.”