It may be the last of its kind.

The American Chemical Society has recognized the chemical hearth that University of Virginia founder Thomas Jefferson worked on with John Emmet, his first natural sciences teacher, as a National Historic Chemical Landmark. A small dedication ceremony is being planned for March.

The hearth, thought to be the oldest remaining example of a hands-on laboratory for teaching chemistry in the U.S., was built around 1825 and located in the Lower East Oval Room of the University’s Rotunda. It had been enclosed in a wall from roughly the 1840s until around 2014, when it was rediscovered as part of an extensive Rotunda renovation and restoration.

“The content of chemistry courses has changed considerably over the past 200 years, as scientists have learned more about the properties and behavior of matter,” said Mary K. Carroll, president of the American Chemical Society and a chemistry professor at Union College in Schenectady, New York.

“But the importance of engaging students in hands-on laboratory experiences, first championed by a few progressive institutions, including UVA, has stood the test of time,” she said. “We are excited to honor the University for its role in advancing this effective and impactful approach to teaching science.”

When renovators reopened the hearth, the conservator found remnants of experiments – parts of tapered glass tubes, broken crucibles, homemade charcoal and small sheets of glass. Mark Kutney, an architectural conservator with the University’s Facilities Management Department, believed Emmet made some lab items as he needed them.

“From some of the fragments we found, it appears they were melting glass tubing and making pipettes, and making small crucibles out of clay,” Kutney said at the time the hearth was exposed. “In some of their experiments they would need to expose materials to high heat and observe the reaction.”

The chemical hearth was built as a semi-circular niche. Two fireboxes provided heat – one for burning wood and the other for burning coal. Under-the-floor brick tunnels fed fresh air to the fireboxes and workstations, and flues carried away the fumes and smoke. Five workstations were cut into stone countertops.

The chemical hearth, built as a semi-circular niche in the Rotunda wall, had two fireboxes that provided heat – one for burning wood and the other for burning coal. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Emmet changed the traditional approach to chemical education by putting the tools into the hands of the students. According to correspondence between Jefferson and Emmet, the professor believed the students needed to be able to perform their own experiments to learn chemistry, not just watch the professor. Students also likely worked at the portable hearths that were also in the room.

The chemical facilities were modeled in part after a chemical laboratory in the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City run by William J. MacNeven, Emmet’s mentor.

Emmet, who started teaching at the University in April 1825, was initially given a small room on the north side of the Rotunda for his first chemical laboratory. He complained the room was too small to properly dissipate heat, making it too hot for the chemical experiments he was running.

Jefferson agreed in June that year to let Emmet use the larger rooms in the Rotunda’s basement for his chemistry classes – one for a laboratory and one for a lecture hall.

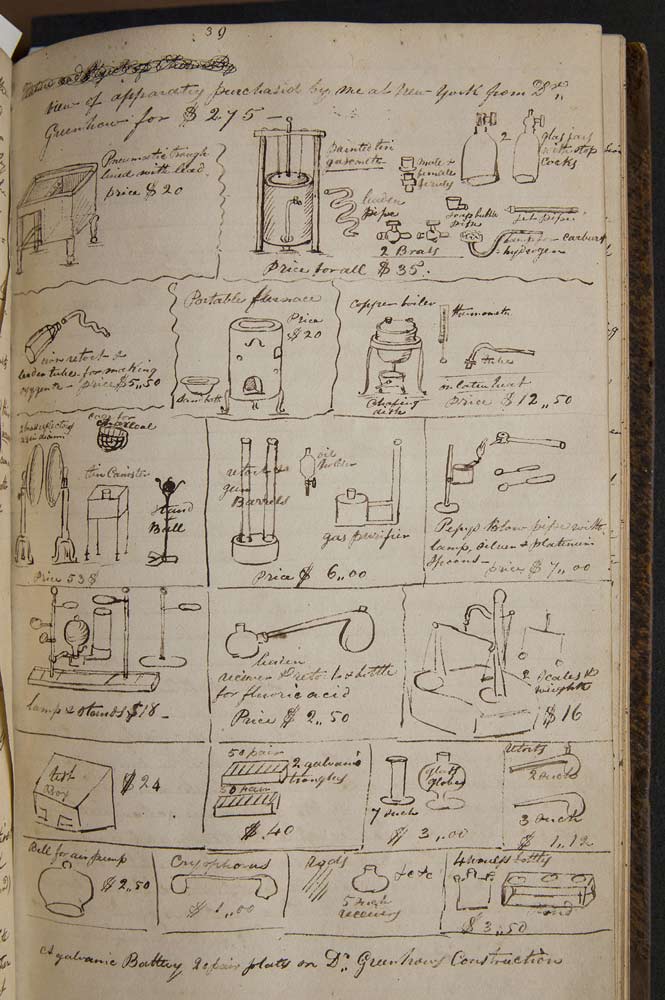

John Emmet, the first natural sciences teacher at UVA, kept drawings of lab instruments he could use and could make himself. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Emmet was plagued with poor health throughout his life, and through his work was constantly exposed to chemicals. A lab accident resulted in sulfuric acid being poured on Emmet, aggravating his conditions, and he took a leave from the University in 1842. He never returned, dying the same year. He was 47.

The chemical hearth was closed in the wall in the mid-1840s when the chemistry laboratory was moved to the southwest wing of the Rotunda. An annex was added to the north side of the Rotunda in the early 1850s, containing four stories of classroom, laboratory and performance space. The chemistry lab was moved to the ground floor and operated there until the annex burned in an 1895 fire.

“The chemical hearth in the Rotunda reminds us of the deep heritage of teaching hands-on chemistry at University of Virginia,” Jill Venton, the current chair of the Department of Chemistry, said. “This is an opportunity to celebrate the chemical heritage of University of Virginia and our unique history to prioritize science education and research.”

Media Contacts

University News Associate Office of University Communications

mkelly@virginia.edu (434) 924-7291

.jpg)