Raymond Shaw graduated from the University of Virginia’s Curry School of Education in 1971 and was a high school biology teacher by trade, but history was his driving passion. After discovering an old Confederate bayonet on his farm in Louisa County, Shaw became fascinated by Virginia’s Civil War history and spent much of his free time hunting for relics from that era.

Following Shaw’s recent death, his family decided to donate some of his finds – relics from the Skirmish at Rio Hill – to UVA’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

The collection includes small pieces of military life that were left behind after the only significant Civil War skirmish in Albemarle County. Appropriately, Shaw’s foray into Charlottesville’s past began on a day that time stopped in his own house.

“It all started because our grandfather clock stopped,” said his widow, Greta Shaw.

An undated photo of Raymond Shaw hunting for Civil War artifacts. His family jokes that this was his favorite posture.

“That’s how we eventually stumbled onto the site,” David Shaw said.

The clockmaker was able to point out some nearby areas that used to be considered part of Rio Road, but had been renamed in the early 20th century.

Armed with this new information and the metal detectors that were always in his trunk, Shaw took David to the area around Rio Hill to search anew. They knew they were on the right track when they walked into the woods and saw rows of earthen mounds.

“In winter huts, the soldiers would build these chimneys and the chimneys collapse over time, so you’ll see mounds and they’ll all be in a straight line and they’ll all be about the same distance apart,” said David.

Those perfect rows of mounds were the first indication that they had discovered the old Confederate campsite.

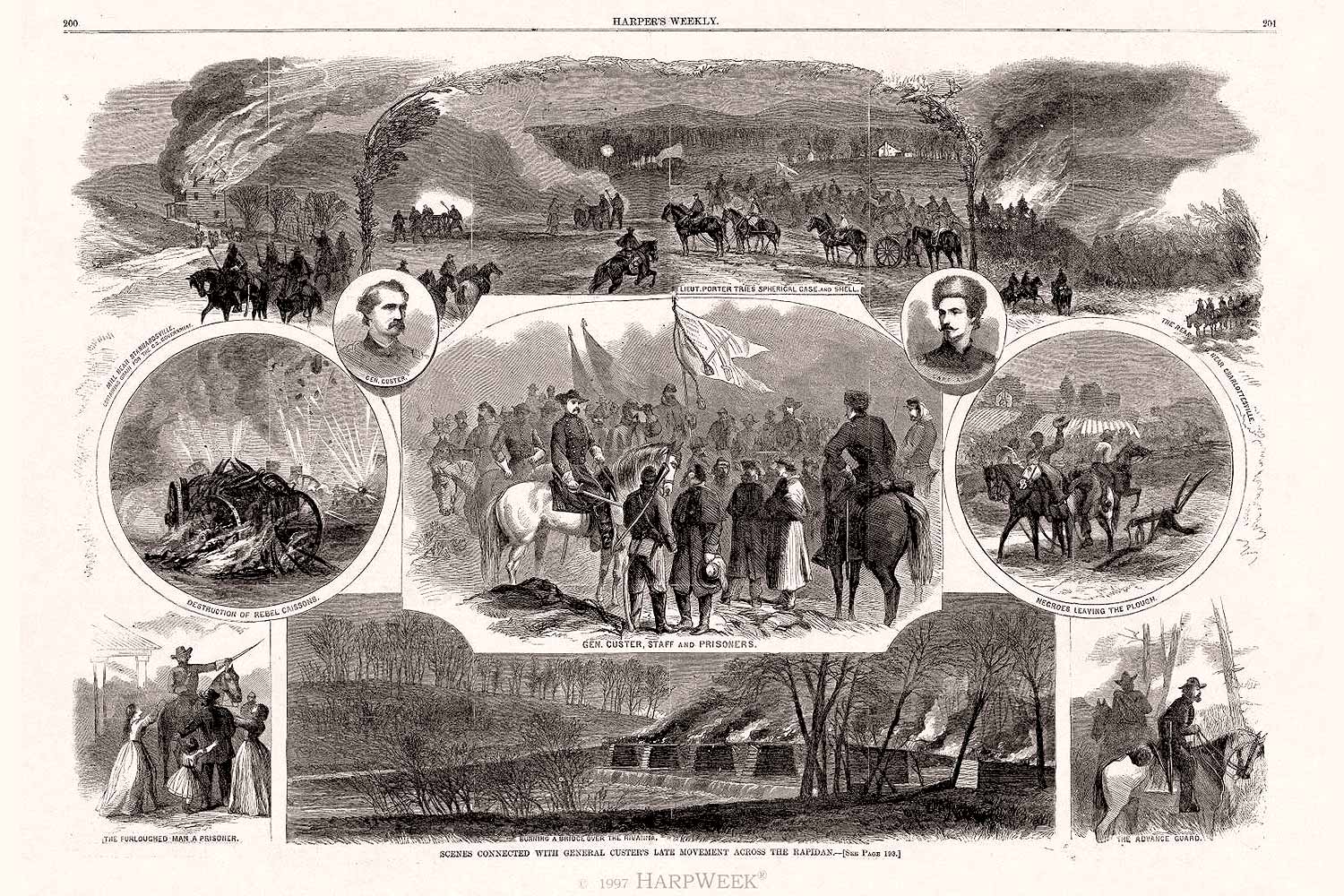

At the time of the skirmish on Feb. 29, 1864, the camp consisted of about 200 men under the temporary command of Capt. Marcellus Moorman. Union forces led by Gen. George A. Custer (yes, that Custer, of Little Bighorn fame) took the Confederates by surprise that day, forcing them to leave behind a number of goods in their hasty retreat from camp – a boon for later relic hunters like the Shaws.

“It was the only camp I’d ever been in where you could still see the outline and size of the winter huts. That fascinated me,” said David. “I started raking all the leaves and finding all kinds of stuff.”

The full Shaw collection provides a window in everyday military life during the Civil War. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak/University Communications)

Apart from the evidence of the men who were there that day, the Shaws found the characteristic remains of battle, including rusted bullets and shrapnel from a Union Schenkl projectile.

“It really tells the story. Each one of these items, when you take them all together, tell what was happening and how folks were living,” said Art Beltrone, a local historian and longtime friend of the Shaws.

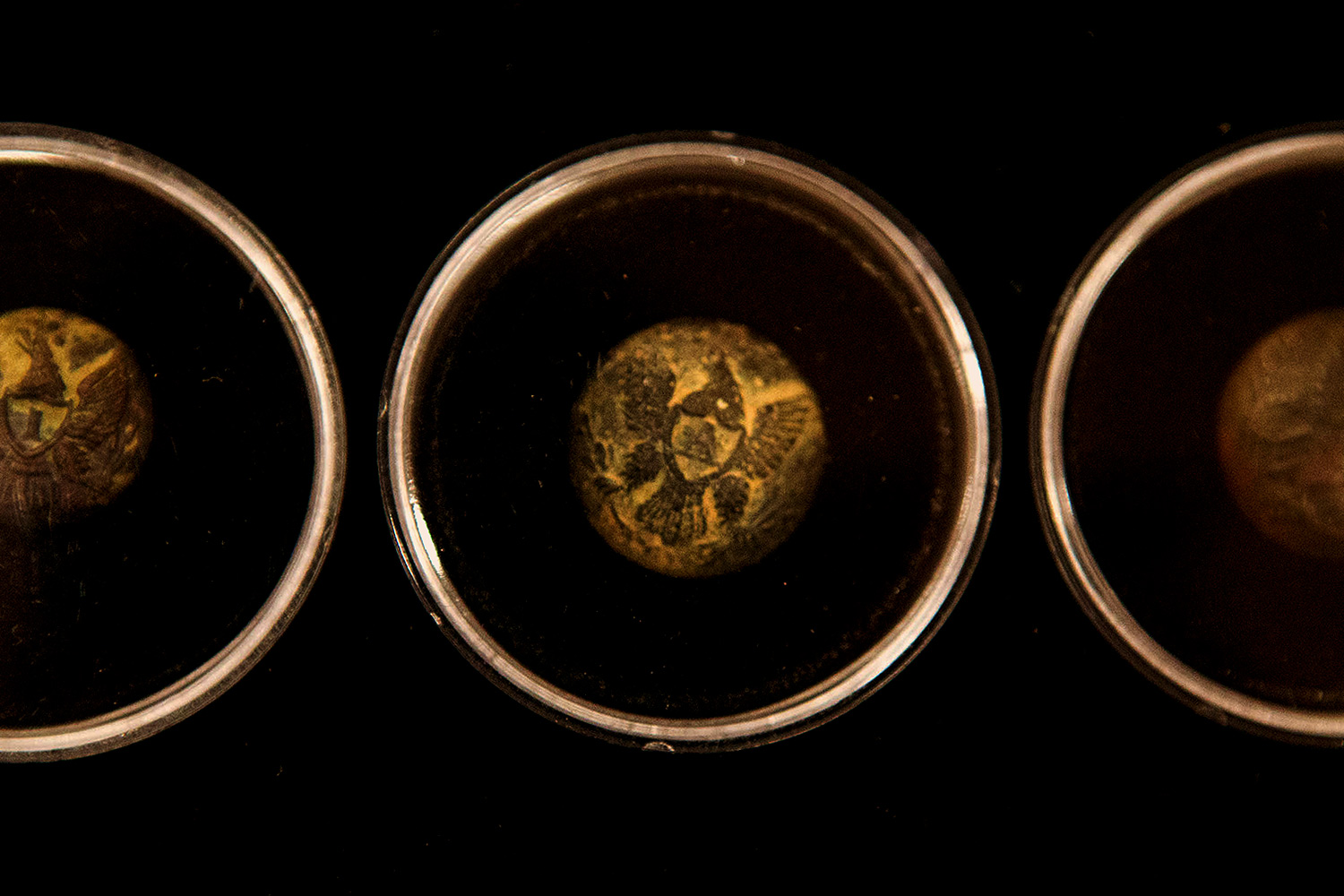

A Civil War Union Eagle “A” Artillery two-piece button excavated from the Rio Hill area. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak/University Communications)

Confederate forces viewed the skirmish as a victory because although the Union forces destroyed their camp, Custer’s men eventually retreated under the false belief that a larger Confederate relief force was on the way. The Union likewise claimed victory because they were able to destroy the camp and distract the local Confederate forces from a larger Union raid happening in Richmond.

A.R. Waud’s sketches for Harper’s Weekly of the events of the Battle of Rio Hill.

“The donation of these artifacts is very important to us,” said Edward Gaynor, the librarian for Virginiana and University Archives. “The site was cleared, so there’s nothing there anymore. The fact that some of this was rescued nearly 50 years ago can tell you things about the men who were there and what was going on.”

Rio Hill Shopping Center now stands atop the site of the old skirmish, but Raymond Shaw’s relic hunting and the generous donation of his family will ensure that the action of the day will never be forgotten.

“In combination with the many letters and diaries we have at Special Collections, these artifacts will give a fuller picture of the Civil War in Albemarle County,” Gaynor said.

Raymond Shaw’s family displays the donation of his Civil War artifacts. From left to right: Gretta Shaw, Lori Pollard, Morgan Shaw (center), and David Shaw. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak/University Communications)

Media Contact

Article Information

June 15, 2016

/content/civil-war-artifact-donation-brings-life-battlefield-special-collections