The school year is almost over, and these fourth-year University of Virginia students have been working against the clock – just as the clock has been working against them.

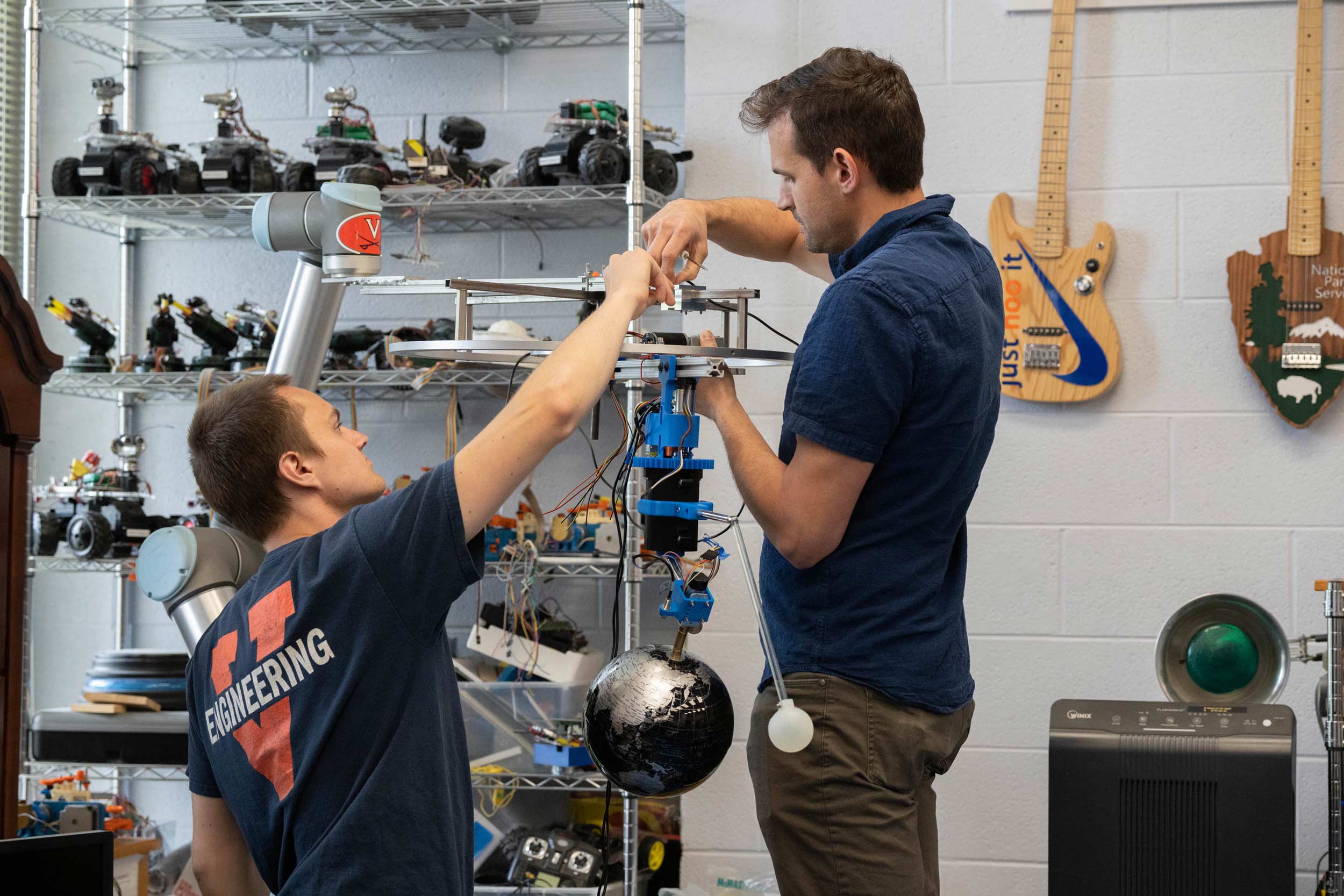

Most of the 13 engineering whizzes taking the inaugural “The Art of Timekeeping” course have been coiled like mainsprings against one enemy in particular: a monumental robotic art clock dubbed “The Sands of Time.”

Six years in the making, the University-themed timepiece was started by student “Gizmologists” taking a capstone course, then shelved until this semester. The ambitious chronometer – that’s the scientific term for anything that measures time – was designed to be the ultimate expression of what it means to go to school here.

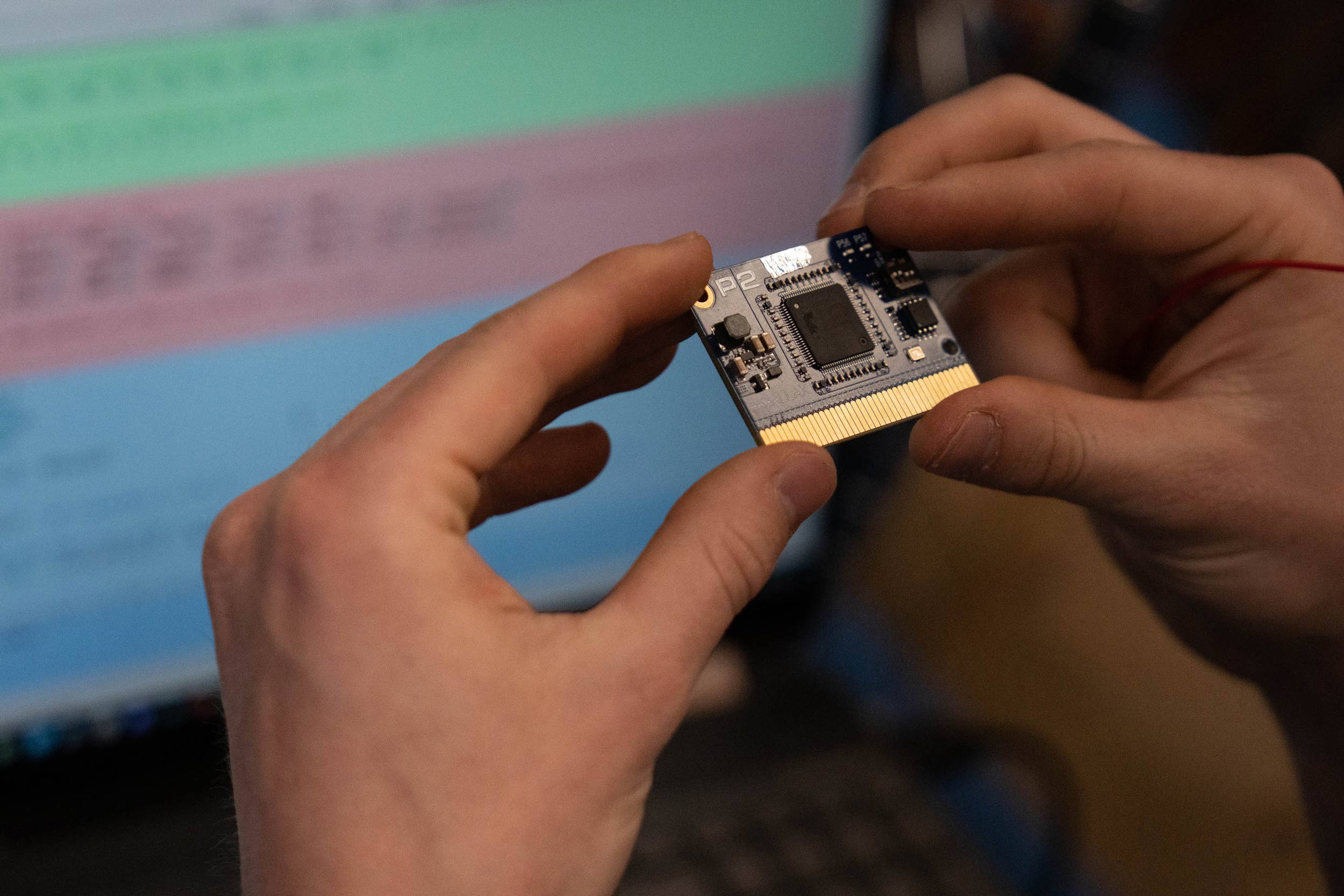

On the one hand, with its 12 sand hourglasses that seem to float in space, encircled by futuristic-looking LED rings and controlled by precision robotics, the clock is meant to be a testament to Virginia’s engineering prowess.

On another, with a Rotunda-shaped mirror at its center, the clock is meant to serve as a truism to which most alums will attest: You’ll have the time of your life at UVA.

But first the students have to get the clock working. Associate professor Gavin Garner said the daring steampunk-style design has resulted in its share of migraines learning moments for his students. That has made its completion by year’s end in no way a given.

“There’s a kind of joke in design and engineering,” Garner said. “There’s a conservation of problems, just like a conservation of energy in physics, where you can never completely get rid of problems, you just convert big problems into smaller, less-important ones that can be swept under the rug.”

This exercise in blood, sweat and gears will end one way or another. But who will win? The students – or their stubborn, unfinished timepiece?

A Whiff of Smoke

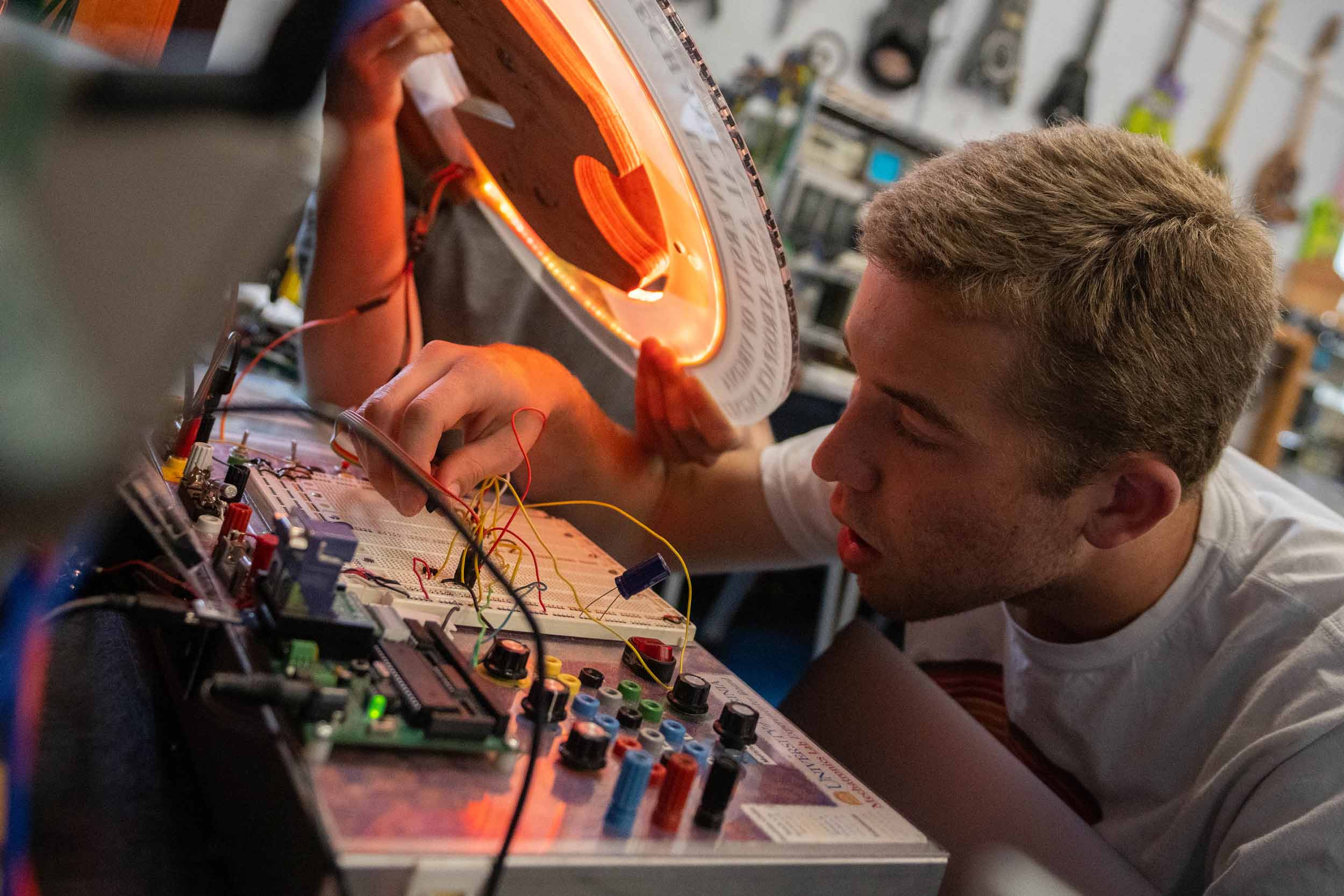

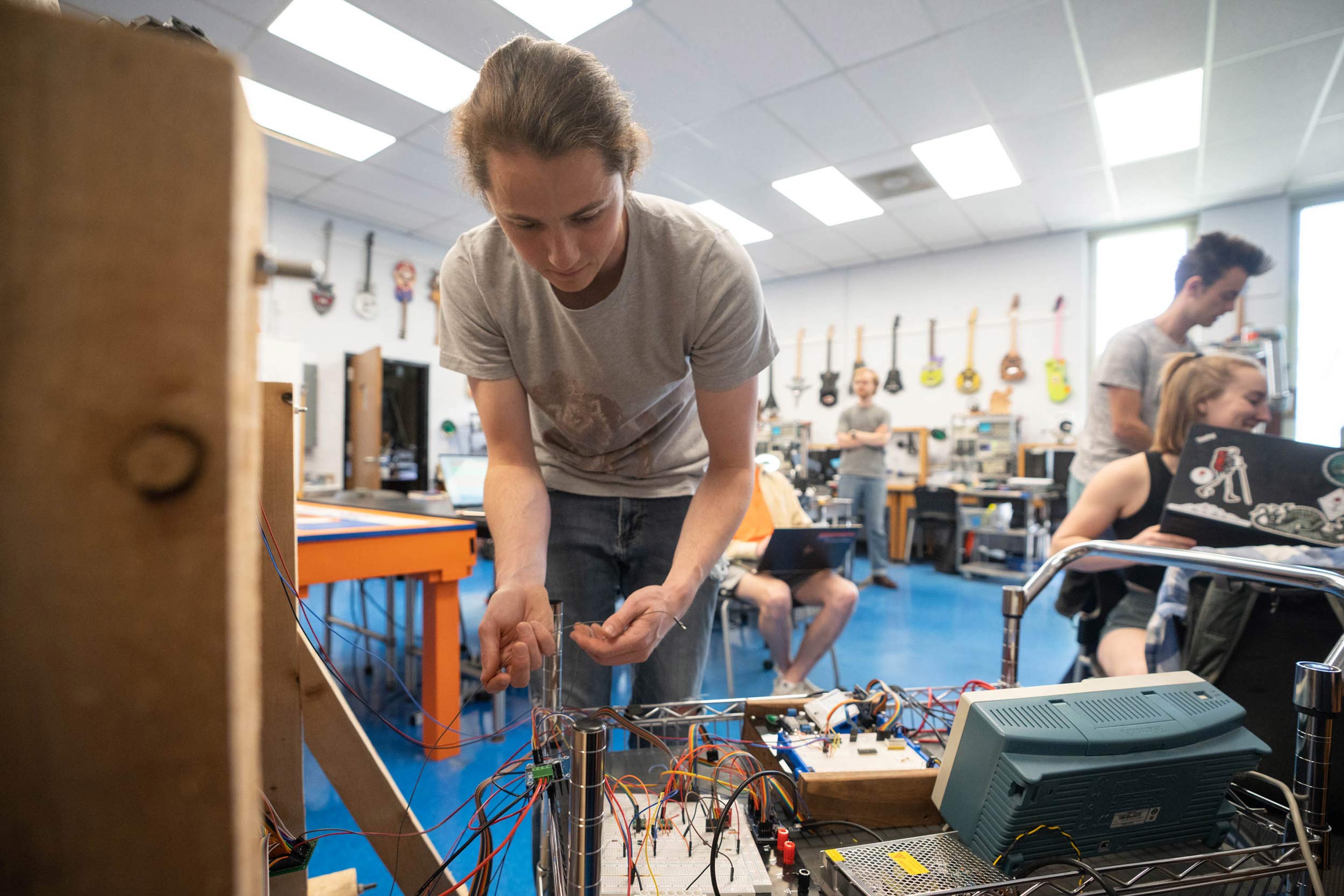

It’s mid-April when UVA Today visits the Mechatronics Lab, one of the rooms in the Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering building where awesomeness is built.

On the walls hangs an assortment of individualized electric guitars crafted by students who took Garner’s Advanced Mechatronics course. One guitar is shaped like a fighter jet. Another contains video of the “Eye of Sauron” from “The Lord of the Rings.” At the center of the room, a table built to resemble a giant cassette tape flashes unnoticed. A pinball machine in one corner goes ignored as well.