The story starts as early as 1837, when a professor wanted more space for himself. A series of Pavilion X expansions eventually swallowed several student rooms, including Rooms 46, 48 and 50. These expansions sacrificed the fireplace and chimney that once served both 48 and 50, and resulted in the construction of a new chimney and fireplace in Room 48, on the opposite wall from where it had originally been.

Expanding pavilions into student rooms was not uncommon in the University’s early years. Over decades, pavilion residents, hotel keepers and professors regularly annexed student rooms to give themselves more living and working space. Floors were lowered, then raised. Doors were cut through walls. Student rooms were converted to pavilion restrooms and, more recently, into accessible restrooms.

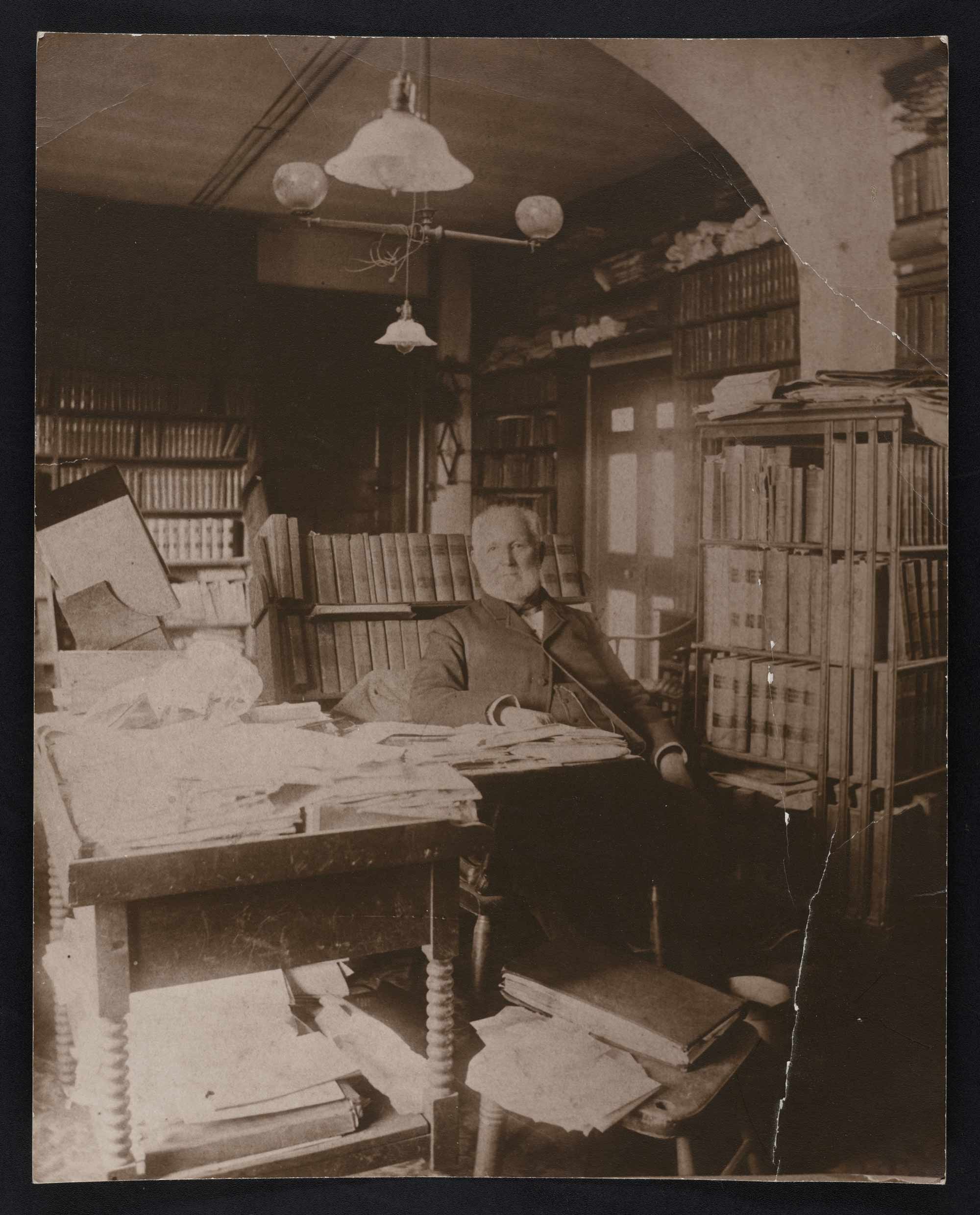

But for a University so steeped in history, there were more than a few gaps in the historical records of these Lawn rooms and the many renovations they underwent. It fell to James Zehmer, Senior Historic Preservation Project Manager of the chimney reconstruction in UVA’s Department of Facilities Management, to sort it all out.

“I’m an architectural historian, so what we do is take physical evidence and documentary evidence and match those two things to tell the story,” Zehmer said. “In this case, I like to think of this as using architectural history to solve an architectural mystery.”

To return the rooms to their original layout, Zehmer first had to understand how they had evolved and why. He compared records from University archives with evidence uncovered when the rooms were dismantled for renovation. He relied on the historic structures report prepared by Mesick, Cohen, Wilson and Baker Architects, in Albany, New York, and Williamsburg. And he worked with floor plans from the different stages of encroachment, many of which came from the Law School archive, since Pavilion X was the home of the professor of law and the law classes for 130 years.

As early as 1837, the Board of Visitors granted permission to law professor John A.G. Davis - who later was shot to death by a masked student on the Lawn in 1840 - to use Lawn rooms 50 and 52 for his purposes.

“By 1839, [Davis] is paying rent on those rooms, so we know he has both rooms,” Zehmer said. “And they would stay part of the pavilion throughout that second pavilion plan, until 1847.”

Zehmer said it was common for professors back then to request more space because the pavilions themselves had relatively small footprints. A first floor was generally a classroom and a dining room. Upstairs was typically a parlor and two living spaces. For professors with families, space was tight.