Professor Anton Korinek’s résumé should give him a high sense of job security. He holds appointments in both the University of Virginia’s Department of Economics and the Darden School of Business. He’s also a Rubenstein Fellow at the Brookings Institution and the economics of artificial intelligence lead at Oxford’s Centre for the Governance of AI.

Korinek has a master’s degree from the University of Vienna in Austria and a doctoral degree from Columbia University. His work has been featured in such esteemed publications as The Economist, The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal.

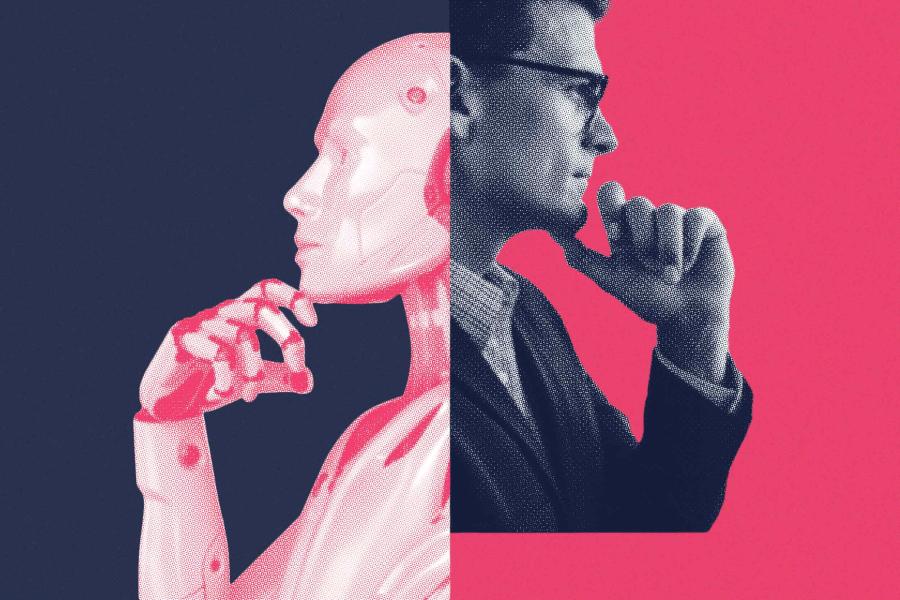

So why is Korinek, 44, already preparing for a time when he becomes redundant in the workplace?

It’s simple: He has a firm sense of the potential realities of AI.

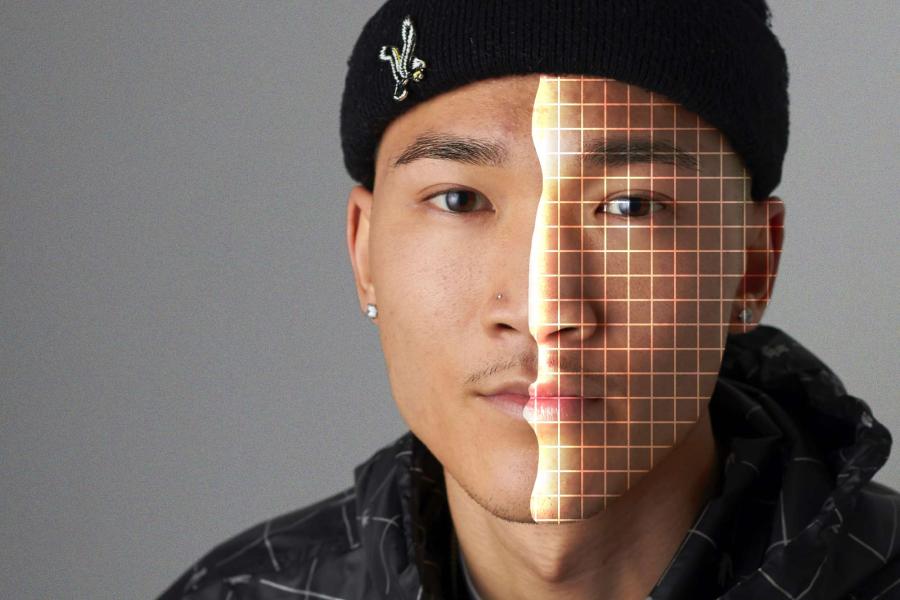

Advancement in AI capabilities drew headlines last week when it was reported that the writing of ChatGPT, a chatbot launched in November, passed a final exam at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business.

To Korinek, it was another step in the rapid progress of AI, something he’s been tracking for decades.

“These systems are advancing so fast,” he said. “What we have seen over the last decade is the size of these systems is doubling every six months. If something is doubling every six months, that means it grows by a factor of four every year and by a factor of 1,000 every five years.

“It’s the speed of progress that really leads me to believe that we’re going to see sky-rocketing capabilities among AI systems. And if you find ChatGPT impressive, wait for the next one to come out in the first half of 2023. And then wait for the version after that in the second half of 2023, and so on.”