In his course on the University of Virginia’s early architectural history, Louis Nelson and his students looked past the magnificent facades of the Academical Village to consider the working and everyday spaces that sustained the University through its first half-century.

By focusing on peripheral, marginal areas behind and under walls and columns, they revealed places hidden, buried or changed beyond recognition that were once vibrant with activity that made up the life of enslaved laborers on Grounds.

Even finding nails in certain places yielded new clues.

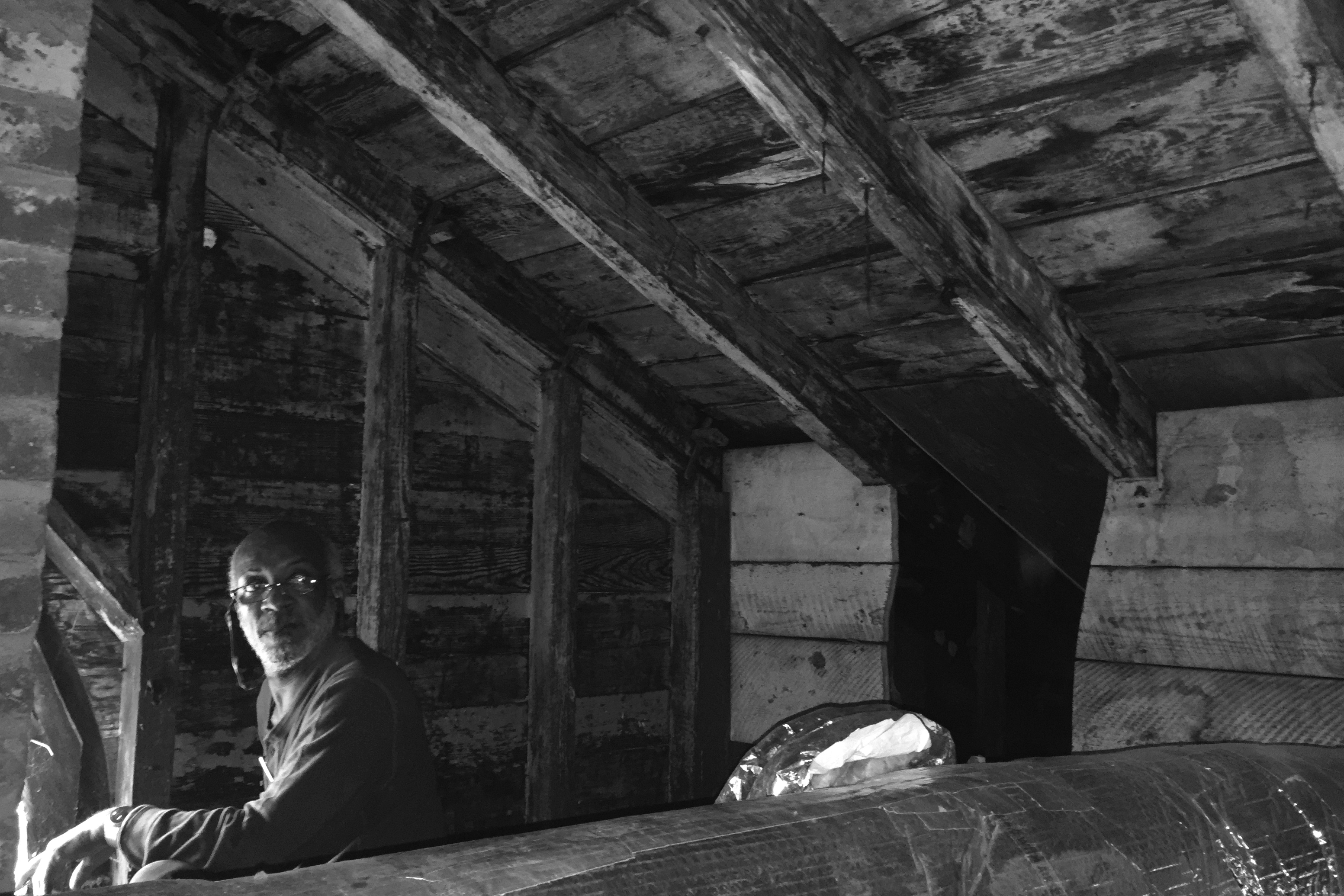

Students in “Field Methods in Historic Preservation” spent last semester crawling with flashlights through attics and cellars looking for physical evidence and logged countless hours poring over old documents. In a related spring class, they will work on the best ways to communicate what they’ve discovered and make it accessible to the public.

Louis Nelson, a UVA professor of architectural history. (Photo by Dan Addison)

Nelson and Andrew S. Johnston, professors of architectural history in the School of Architecture, are teaching the course in two parts.

“The spectacular pavilion gardens we now enjoy supplanted – and for a long time silenced – the daily labor of chopping wood and cleaning fowl that once animated these zones,” wrote Nelson.

In recent years, UVA faculty, staff and students have been working on several projects to rediscover the experiences of enslaved laborers who helped build the University and worked for its white professors, their families, and the University students in the early decades. A new cadre of students is helping fill in “a more honest history of the Academical Village,” as Nelson put it during a recent public event that was part of UVA’s community celebration of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Graduate and undergraduate students in the field methods class described some of their findings, including evidence of expanded basement areas where slaves likely lived and worked doorways that allowed patterns of movement from basement areas to added exterior kitchens, and open spaces that were probably bustling with a range of activities.

For most of the University’s nearly 200 years, the narrative that Jefferson didn’t allow students to bring slaves to school with them minimized and even suppressed their integral place in and contributions to UVA, “without which this place would’ve collapsed,” Nelson said. He noted that professors commonly owned and housed five to 15 enslaved persons in and around their pavilions, and hotel-keepers owned up to 25 or more.

“Thomas Jefferson, in his designs for the Academical Village, insufficiently accommodated enslaved laborers,” Nelson said. Furthermore, “through the structuring of architectural space, he suppressed the visibility of the landscape of slavery.” Jefferson first did that at his home, Monticello.

In the subsequent decades, the population on Grounds grew much bigger. Pavilion residents and slaves expanded and transformed some of the Academical Village’s living and working spaces. After emancipation, free African-Americans worked on Grounds as day and night laborers, and even ran small enterprises such as a barber shop, keeping up constant activity, Nelson said.

“One of the principal responsibilities of student teams,” he said, “was to try to collect all of this physical and material data and then integrate that with both the historical evidence that might be known about that specific site, together with broader patterns of workflow from comparable antebellum great-house sites in Virginia and across the upper South.”

Hutch Landfair, a student in “Field Methods in Historic Preservation,” uses ground-penetrating radar equipment to help identify foundations of now-missing buildings. (Photo by Erin Que, another student in the class)

Historic-structure reports have been compiled for various buildings on Grounds, but less is known about basement areas below students’ Lawn rooms and adjacent outdoor spaces that are now paved for parking. The class used ground-penetrating radar in what are now the gardens behind the pavilions and in the parking lots that were formerly work yards, Nelson said. “The radar was used to help identify foundations of now-missing buildings.”

He said UVA’s Office of the Architect and Facilities Management staff were very helpful and trained the students on how to use that equipment.

“There are no historical reports for the student basement rooms like there are on the pavilions,” said Kenta Tokushige, a second-year graduate student in architectural history. “It was fun to do this work and make creative connections.” Although his focus is Japanese shrines and temples, he said, “UVA is a UNESCO World Heritage site – I couldn’t pass that up. Plus, this gave me a comparative view.”

Below one of the students’ Lawn rooms, hand-cut wooden laths show a ceiling was added when the basement was refurbished into a sleeping area. (Photo by student Kenta Tokushige.)

From the students’ research, it is likely that several areas were outfitted as sleeping quarters for slaves in these basement spaces. The student teams found more evidence of the addition (not included in Jefferson’s plans) of separate kitchen buildings, as the small brick house known as “the Crackerbox” behind Hotel F was first used, with doors and paths to and from the kitchens to rooms.

Under and adjacent to Hotel A, currently being renovated, and nearby Lawn rooms, students found a comprehensive work space with a sunken yard and two rooms that probably housed enslaved workers.

In addition, one team further explored evidence below room No. 24 of a cistern that was built into the ground and later filled in, plus wooden pipes that carried the water, graduate student Kelly Woods Schantz said. The team worked to understand that cistern as part of a sequence of spaces and infrastructure managed by enslaved African-Americans, Nelson added.

Another team, analyzing an area near Pavilion VIII, found “an incredibly interesting narrative regarding the coexistence of enslaved spaces with those of the students at the University,” said Matthew Janus, a third-year student majoring in government and minoring in architectural history. It seems that some students, who were not supposed to gamble, played marbles in an area that was also a work yard. “We think, as Professor Nelson mentioned, that spaces of play at early UVA must have overlapped, and that tidbit of information was incredibly novel and interesting to my teammates and I.”

“I’m incredibly interested in early American architecture,” Janus said, “and in particular how the environments of enslaved African-Americans coexisted with the environments of free laboring and elite whites in early America. I think how African-Americans navigated this extremely hostile landscape is fascinating, and I took Professor Nelson’s class to continue to explore this interest.”

“I found the students to be deeply invested in this project, and that remains gratifying.” - Louis Nelson

Nelson said another of the eight student teams explored the basement under Pavilion IV that led to “a clear understanding of how [the rooms] functioned and how the occupants adapted the area over time to meet their needs.” He said there was a circular pattern of movement between the rooms to an exterior kitchen and work yards.

“Now we have hard data,” Nelson said.

The students’ work also points to “opportunities for intervention” as Schantz said – whereby they can use the information and details to recreate stories about how enslaved laborers, and then free black workers, contributed to daily life at UVA.

They also examined documents found over the years, some of which have been collected online in a digital project, “Jefferson’s University … the early life,” an online searchable database of early University records.

“I found the students to be deeply invested in this project, and that remains gratifying,” Nelson said. “As we all know, the students of the University of Virginia care deeply about this place. That said, they also want to make sure that we work to transition from a love of place derived from false mythologies to a commitment to UVA that acknowledges historical reality, and in so doing embracing Jefferson’s direction to follow truth wherever it may lead as we move forward into our next two centuries.”

His colleague, Andrew Johnston, who directs the School of Architecture’s Historic Preservation program and is teaching the second-semester class, said students this semester are determining, “What are the stories and how do we tell them in the best ways?”

Through both individual and group work, students will consider using technologies including digital representation, computer-aided modeling and 3-D printing to make models of what some of the outbuildings might have looked like, as well as more traditional means, such as drafting by hand, Johnston said. This work is being undertaken as an initiative associated with the “Jefferson’s University” digital project, the ongoing restoration work in the Academical Village and the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University, an initiative to understand and commemorate the landscapes of slavery at UVA.

The students will work toward creating an exhibition that Johnston said he hopes will eventually be shown in the Rotunda when it reopens after its restoration.

Media Contact

Article Information

February 15, 2016

/content/course-examines-slave-life-academical-village