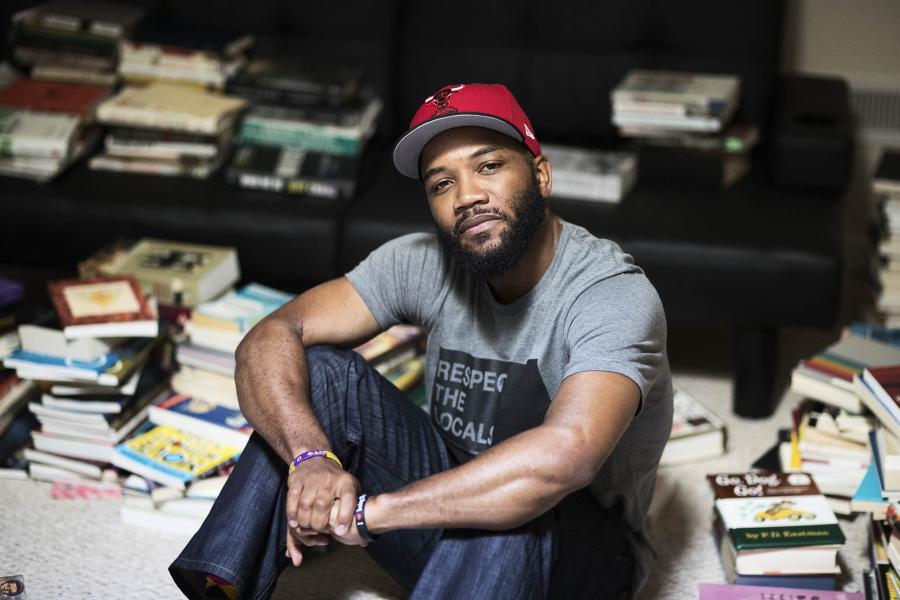

A.D. Carson begins his day at 7 a.m. on this morning in March with a walk across the University of Virginia’s Grounds, passing below still-lit streetlamps. In his headphones, Saba’s “Few Good Things” album plays, followed by the “Dilla Time” audiobook by Dan Charnas. He makes his way to UVA’s Rap Lab.

Carson is an assistant professor of hip-hop and the Global South in UVA’s Department of Music. Before coming to Charlottesville, he earned his Ph.D. in rhetorics, communication and information design at Clemson University.

His doctoral dissertation, an album titled “Owning My Masters: The Rhetorics of Rhymes & Revolutions,” was recognized by Clemson’s Graduate Student Government as the 2017 Outstanding Dissertation. A mastered version of the album has been peer-reviewed and accepted for publication this spring with University of Michigan Press, five years after its debut.

His most recent album, “i used to love to dream,” also released by the University of Michigan Press, is the first rap album peer-reviewed for publication through an academic press. Because of the pandemic, Carson only recently was able to perform live what’s on the album, which won a Prose Award from the Association of American Publishers and UVA’s Research Award for Excellence in the Arts and Humanities.

“I hate that it was released during the pandemic, because this past week was the first time I’ve been able to listen to the project in a space with other people, and that is such an important part of music,” Carson says.

During the disruption, Carson started working on a new album, titled “talking to ghosts.” The 13-track album is expected to be released April 13.

“Initially I made the album, and I didn’t know I was making an album. I just thought I was working through challenging personal and academic questions during the pandemic,” he says. “All of these people were passing away, and we had to become accustomed to this tragedy and a perpetual state of mourning. I started writing and recording to deal with the heaviness of it all.”