A.D. Carson read his first poetry book as a fourth-grader in central Illinois, when he asked his teacher if he could make his writing assignment rhyme.

Decades later, Carson – now a University of Virginia professor of hip-hop and a prolific rapper – still loves writing rhymes.

“Writing is how I feel my way through new spaces,” Carson said, speaking shortly after moving to Charlottesville from Clemson, South Carolina, where he earned his Ph.D. from Clemson University. “I have been here for a week and recorded two pieces already.”

It was Carson’s writing – and his talent for crafting compelling rap lyrics – that led him to create arguably the most unique dissertation in Clemson history, and one that garnered media attention worldwide. Instead of a typical dissertation – pages and pages of text and citations – Carson wrote, performed and produced a 34-song rap album, “Owning My Masters: The Rhetorics of Rhymes & Revolutions.”

A.D. Carson joined UVA this summer as a professor of hip-hop and will begin teaching this fall.

Tracks on the album – which begins with a riff on the Confederate anthem “Dixie,” before launching into raps weaving together history, literature, art and current events – have attracted tens of thousands of YouTube viewers, more than 60,000 listeners on SoundCloud and more than half-a-million hits on Facebook. The quality impressed faculty members in Carson’s rhetorics, communication and information design doctoral program, and ultimately caught the attention of faculty members in UVA’s McIntire Department of Music. Carson was hired as an Assistant Professor of Hip-Hop and the Global South this spring. His appointment builds on the legacy of Kyra Gaunt, a former professor of ethnomusicology at UVA from 1996 to 2002, who helped pioneer hip-hop studies at UVA and nationwide.

1998 music graduate Erik Nielson, called Gaunt "one of the forerunners of hip-hop scholarship." UVA, he said, gave her research an early platform.

"Her scholarship really helped redefine what hip-hop is and revealed the role that women and girls play in the importance of hip-hop," said Nielson, who now teaches hip-hop at the University of Richmond.

Gaunt, now about to join the faculty at the University of Albany, taught classes on African-American popular music, particularly focusing on the art of deejaying and the dance culture that came with hip-hop music. She often brought local DJs in to perform for students, and wrote about her class for a top academic journal, Musical Quarterly, sharing her innovative approach. It struck a nerve at UVA, attracting nearly 100 students just in her first semester.

"I believe I set a precedent of immersing yourself in the firsthand, personal study of making music, making hip-hop, as opposed to simply studying the lyrics," Gaunt said. She said she had followed Carson's work at Clemson closely, and was glad to see him choose UVA.

"Those of us in hip-hop were very excited to see what he has done," she said. "Having him at UVA will be such a draw for students who are musically inclined and also want to get a Ph.D. studying hip-hop. Perhaps it will send a ripple through music departments throughout the country."

Current faculty members are eager to see what Carson will add to Gaunt's legacy.

“Hip-hop is arguably the most important and of-the-moment form of popular music worldwide. We were looking to fill a space in our department that our students had expressed a lot of interest in,” said associate professor Ted Coffey, who chaired the search committee that selected Carson. “We had a lot of excellent candidates, but we were really excited about what A.D. could add to all three of our department’s focus areas: scholarship, composition and performance.”

The committee, Coffey said, was also very impressed by the dissertation, the first of its kind they had ever seen.

Carson defended his dissertation at Clemson in March, earning high marks from faculty members in his doctoral program. (Photo courtesy of Kenneth Scar, Clemson University)

Just as dissertation essays quote from literary or historical texts, Carson quotes the sounds and people that inspire him with lyrics, sound clips and ideas from figures like novelists Ralph Ellison, Sylvia Wynter and James Baldwin, activists like Malcolm X and hip-hop artists like Jay Electronica and Curren$y.

“I imagine standing in a cipher with all of these literary and scholarly greats,” Carson said. “They have offered up all of these words and ideas, and you can kind of snatch lines out of the air and speak back to them.”

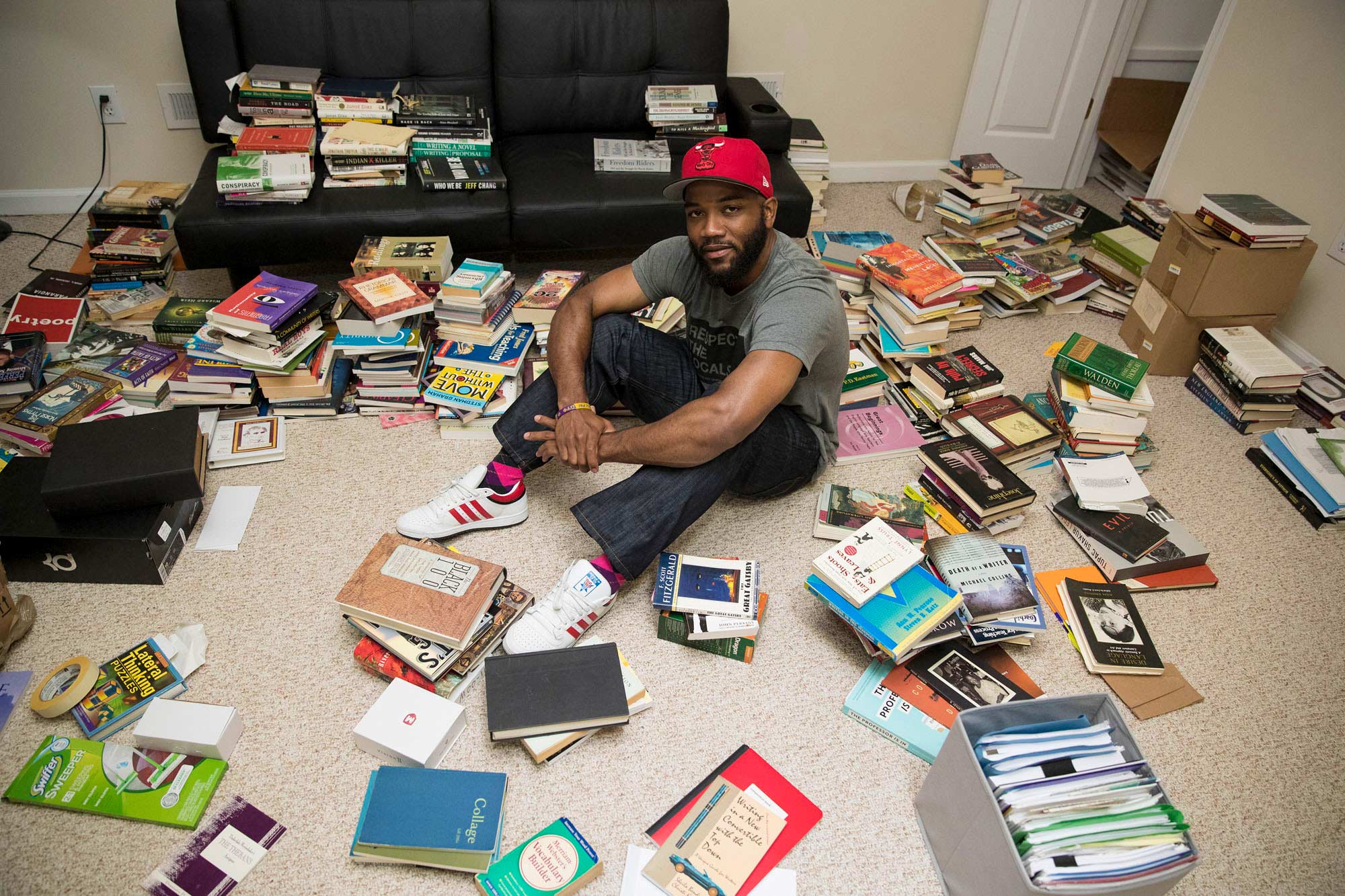

Carson in his new home in Charlottesville, amongst the extensive collection of books he relies on as he writes new songs.

He also captured the raw emotion and tension of events that dominated news headlines as he wrote. The timeline Carson created to accompany his thesis is a laundry list of recent tragedies. There are lists of black men and boys killed by police; reminders of mass shootings in Orlando, Charleston and too many other cities; and records of racially charged incidents on Clemson’s campus, from a December 2014 “Cripmas” gang-themed fraternity party to debates about Confederate memorials and monuments.

“It was almost like a sensory overload, with all of these events and information coming from all directions,” he said. “The only thing I knew to do was write rhymes about it.”

This year, Carson will teach three classes at UVA: two writing and composition classes and one class, “The Black Voice,” exploring the expression and repression of black voices in America. Just as he did at Clemson, he wants to do what academia is supposed to do best: start an honest conversation.

Hip-Hop: No Translation Needed

Though hip-hop has long been a subject of academic study, with professors and students examining and expounding upon its history and cultural significance, Carson said, even among the great work many scholars are doing in the field, hip-hop presented in academia risks being translated or sanitized in some way.

“It is something I have felt sitting in a classroom, where there is a conversation going on and I have an example to contribute,” he said. “Quite literally, what would happen is I would make a statement and then someone else would rephrase my statement so that it was more legible or familiar to people in the room.”

Carson rehearsing in his home studio.

Occasionally, he said, he has been asked to restate his rap lyrics “in plain English.”

“Rap music in America, for the most part, is already written in the language that most of us speak,” he said. “Maybe, instead of asking for a translation, the best response is to re-read it, try to listen more intently and try to empathize and understand where the artist is coming from.”

That’s why Carson chose to submit his dissertation as an album, keeping the raps in their raw form.

“I wanted to resist that urge and call into question the necessity for translation, because I don’t think it is necessary in most cases,” he said.

Similarly, Carson’s lyrics do not shy away from or disguise the issues and events weighing on his mind. While at Clemson, Carson was a vocal participant in campus sit-ins, vigils and conversations about racism and race relations.

He captured the emotion of those efforts in one of his tracks, “See the Stripes.” The song, playing on the black stripes of Clemson’s tiger mascot, spawned an eponymous campus-wide campaign raising awareness of the legacy of slavery and black history at Clemson.

One lyric reads: “And I say/The Tiger cannot survive without its stripes./We cannot ignore/the troubling history that brought us to this,/our glorious institution/with its memorials and monuments to ‘honorable’ men,/and call ourselves a family/And we’re damned if we think we’re doing ourselves any favors/coloring the history one hue.”

Bringing hip-hop directly on campus, Carson said, allows more voices to be heard.

“Hip-hop presents work in a particular voice, in a particular way,” he said. “There might be people who refuse it as a serious course of study, but when they do that, I think they are reproducing, on some level, the problem that we have going on all across the country, of favoring certain voices over others.”

At Clemson and now at UVA, Carson wants his work and his actions to shed light on all of that history, to bring in more and more voices and to start conversations among faculty members, students and the public – even when those conversations might be awkward or painful.

The Conversation Continues in Charlottesville

Carson moved to Charlottesville just a few days after a May 13 white supremacist rally in Lee Park, which was widely condemned by city leaders.

That rally, Carson said, was a reminder of the importance of having honest, open and difficult dialogue about the state of race relations in the United States and the obstacles that stand in the way of improvement, whether systemic discrimination or extremism like that on display at Lee Park.

“It seems to me that UVA has approached this position and these conversations with a desire to be pushed in ways that might be uncomfortable, but that will help us be able to have the conversations we need to have, which is what I am interested in,” he said. “My work is what it is, and it is going to challenge what it will challenge.”

When he first heard about the UVA job posting, seeking a professor of hip-hop, Carson said it seemed tailor-made for him.

Carson records music at home and also hopes to help student musicians record music at UVA.

“I had several people send me the job posting out of the blue, because it seemed so specific to what I do,” he said. “To me, it was preferable to any other opportunity I saw.”

Coffey’s faculty search team agreed.

“It’s a different, more enriching experience to learn from someone who is deeply embedded in their field, as A.D. is with hip-hop,” Coffey said. “We are really excited about who he is and the ideological work that he will be doing, teaching hip-hop from the point of view of a practitioner.”

Carson hopes to serve as a center of gravity for UVA students already composing and producing hip-hop around Grounds, building on momentum from hip-hop great 9th Wonder’s visit to UVA in March.

“There is already a hip-hop community at UVA, but it is fractured in some ways, with many students not knowing about the work other students are doing,” Carson said. “Having this professorship will help those students come together.”

He plans to offer weekly listening and writing labs, where people across the UVA community can listen to one another’s work and offer feedback. Eventually, he said, he would love to advise undergraduate and graduate students interested in producing work like his own dissertation.

“I wanted my project to create a point of reference for other students who wanted to present their work in less-traditional ways,” he said. “Ultimately, I want to bring the hip-hop that I love, that I create – that I am – into academia and hopefully provide access for other folks who see themselves in those kind of expressions.”

This article has been updated to remove the word "first" from the headline and to provide additional context on past scholarship at UVA.

Media Contact

Article Information

June 22, 2017

/content/meet-ad-carson-uvas-professor-hip-hop