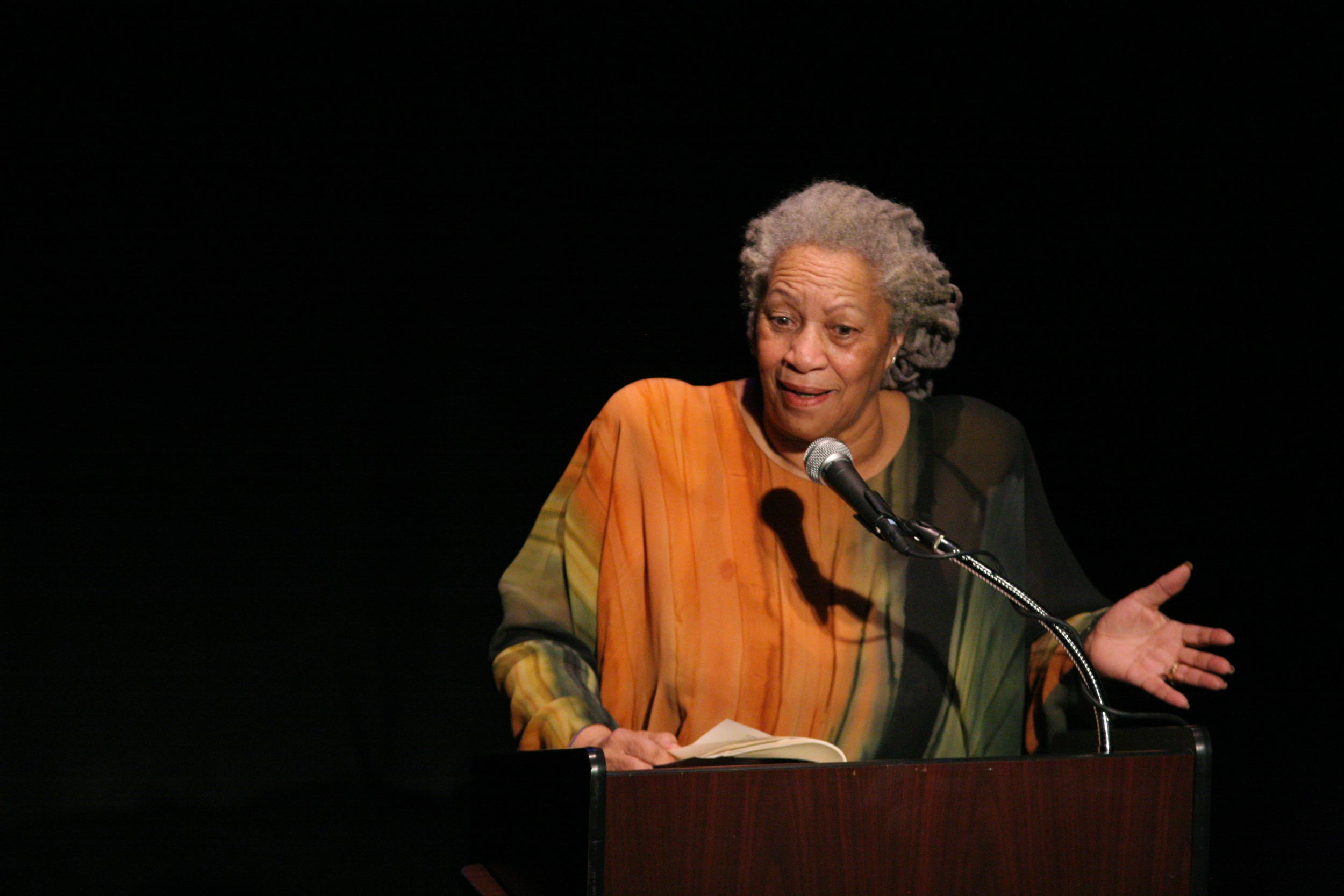

Toni Morrison, who earned many accolades for her fiction that delved into black experience, died Monday at age 88. In 1993, she became the first African American, as well as African American woman, to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The author, who also wrote plays, essays and children’s books, had worked as an editor at Random House and was a professor of literature at Princeton University.

“She lived a long, rich life,” said Deborah McDowell, Alice Griffin Professor of English at the University of Virginia, who specializes in African American literature, especially in the women writers of the tradition.

McDowell not only taught Morrison’s fiction and nonfiction in her courses, but also knew Morrison (though she can’t recall when they first met). She thinks it might’ve been when McDowell was invited to Cornell University in the ’80s to pay tribute to Morrison (who had earned her master’s there), likely to celebrate the Pulitzer Prize for “Beloved.”

“I met her first through her writing, of course,” McDowell said. “But I don’t know when I didn’t know her. I was frequently in her company over the past 30 years.” Morrison sometimes invited people to join her at special events and conferences; in one memorable example, McDowell accompanied Morrison and others to France for the launch of the French translation of her novel, “A Mercy,” about 10 years ago.

On Twitter, McDowell – from memory – and many others shared some favorite Morrison quotes, such as: “Just circles and circles of sorrow” and “Love is no better than the lover. Wicked people love wickedly, violent people love violently, weak people love weakly …”

English professor Deborah McDowell not only taught Toni Morrison’s fiction and nonfiction, but also knew the author personally for many years.

Although “her heart was heavy” with sadness, McDowell, who directs UVA’s Carter G. Woodson Institute for African American and African Studies, took time out from her vacation to talk about some of the high points of Morrison’s work with UVA Today.

Q. What makes Morrison’s work so significant in American literature?

A. Personally, I appreciated that she was someone dedicated to her craft, so dedicated. She was one of the most prolific, politically astute and philosophical writers this country has known. Like so many have said, it would not overstate the case to call her ‘a national treasure,’ as President Obama described her. When Obama conferred the National Medal of Freedom on her [in 2012], he understood that stature. There are writers and scholars and teachers and artists, and then there are writers and scholars and teachers and artists who are in a universe all their own; that was Toni Morrison.

Her work will live forever. We are fortunate she left such a rich and substantial body of work – all that she produced, but then there is all the work and all the writers she nurtured during her tenure as an editor, including Angela Davis, Gayl Jones, Henry Dumas and Muhammad Ali. And this was while doing the seemingly impossible task of writing and bringing up two sons. By the way, one of her sons, Slade, would go on to write children’s books with her.

Beyond her novels, she was a critical theorist and a consummate essayist – in “Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination” [published in 1992], she gave us an understanding of race and the workings of race in the U. S. literary and cultural imagination.

Q. What do you think accounted for the commercial and critical success of her work?

A. The strength of the work, for anyone who loves good writing and appreciates a writer consistently at the top of her craft. Her books on tape are mesmerizing. She did all of her audio books, and she has a mesmerizing voice.

Despite the critical success of her work, it was not commercially successful at the start. Not all embraced her work. Many critics misunderstood it, perhaps willfully. Others found her work difficult and impenetrable, but in my view, they would be lazy readers. And let’s not forget that some of her work was banned in high school curricula (“The Bluest Eye”), and “Paradise” was even banned in prison. She was fiercely uncompromising and did not suffer fools, whether in writing or in person.

“There are writers and scholars and teachers and artists, and then there are writers and scholars and teachers and artists who are in a universe all their own; that was Toni Morrison. ”

- Professor Deborah McDowell

Q. When did you first read her work and begin teaching it?

A. When I was a graduate student. She was part of that efflorescence of writing by black women in the 1980s that included the works of Shirley Ann Williams, Alice Walker, Gayl Jones, Toni Cade Bambara and others. While the literary establishment frequently misunderstood – and at times belittled their work as narrow and too focused on race and black people – the tiny band of black female literary critics in the U.S. academy fought to have their work recognized and taught in the classrooms across the country. I began my own career at a small liberal arts college in Maine teaching the work of Toni Morrison and included a chapter on “Sula” in my first book [“‘The Changing Same’: Black Women’s Literature, Criticism, and Theory”].

I would never want to restrict myself to teaching just one of her novels, but if I could teach only one, it would be “Beloved.” It is a challenging book, so for those who may want to ease into Morrison’s corpus, I often recommend “Song of Solomon” for its narrative genius, its musicality and its memorable characters. Who could ever forget Pilate, the woman without a navel, who carried her name in a brass earring?

Q. Of her 11 novels, do you have a favorite?

A. Of all the novels, my favorite remains “Sula” [her second novel] for its sheer poetry. I’ve read passages aloud to students for the sheer beauty and lyricism of it, and because it’s deeply philosophical. I often joked with Toni that she was one of the best philosophical novelists of the 20th century.

Q. Is there something you think everyone should know about her and her work?

A. Well, in light of where we are right now in time, having witnessed two more in a succession of mass murders, I would say people need to know that she understood – deeply and fully – the nature and origins of white supremacy and its undercurrents of its violence – why the ideology existed, who sustained it, and why.

But on a more positive note, what everyone should also know about her work is that it shows an intimate knowledge of the richness and beauty of black people, of black culture. Her treatment of black life and culture comes with love and celebration, without apology. As she often put it herself, she worked to free herself as a writer from “the white gaze.” She was right in noting that much African American writing seemed historically to be pleading with some imaginary white reader, defending black people against some assumed pathology or deficiency. She was among a group of writers who felt no need to explain black people to white people. Readers, especially black readers, will understand and see themselves – their frailties, their delights, their brilliance. As she was wont to say, I write about black people, about African American culture – the good, the bad, the indifferent. That was for her, “the universe.”

Media Contact

Article Information

August 7, 2019

/content/deborah-mcdowell-lauds-powerful-prose-her-friend-toni-morrison