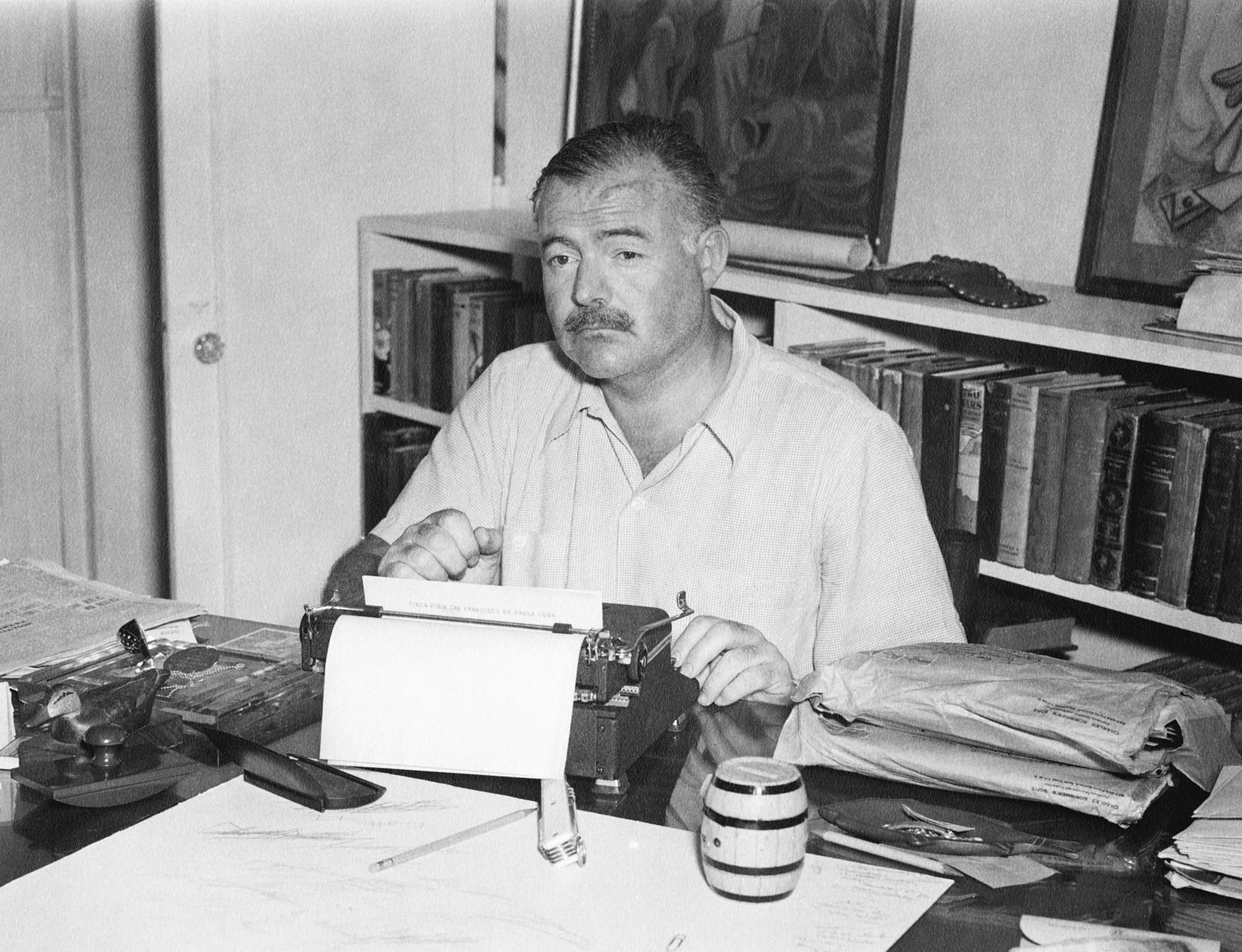

A former student connection circuitously led University of Virginia English professor Stephen Cushman to join a varied group of writers and scholars who discuss Ernest Hemingway in a new three-part PBS series from filmmakers Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, “Hemingway,” which begins Monday.

Hemingway is a towering, controversial figure of 20th-century American literature, whose prose has had a profound influence on writing for almost 100 years. Burns and Novick wanted to “uncover the man behind the myth” and reveal his complex, complicated life, they say on the show’s website. Yes, he wrote about macho subjects such as war, bull-fighting and big-game hunting, but there was a lot more to him than the persona he portrayed to the world, as the documentary shows.

Hemingway, who wrote from World War I through the 1950s – with some work published posthumously after he died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound in 1961 – became well-known for his non-fiction, novels and short stories, and especially for his style of writing.

“My connection to the documentary came through Burns’ collaborator, Lynn Novick, whom I taught in an American literature survey at Yale in the early 1980s,” Cushman wrote in an email, saying he was proud to be a program adviser on the series.

Lynn Novick, left, and Ken Burns, are co-directors of a three-part documentary that revisits the life and work of Ernest Hemingway. (Photos by Stephanie Berger, left, and Evan Barlow)

With more than 30 years of documentary filmmaking, Novick has worked on seven acclaimed series with Burns, including “The Vietnam War,” “Baseball” and “Jazz,” as well as creating the 2019 PBS series, “College Behind Bars,” her first solo work as director, with Sarah Botstein as producer.

Cushman said it remains true that “no 20th-century American author has had as big an influence on the way ordinary literate Americans write American English as Hemingway.” The writer’s style is deceptively simple and an iceberg, he said, with a lot more going on below the surface.

In the first episode, Cushman responded to the reception of Hemingway’s book of short stories, “In Our Time,” published in 1925. Hemingway wrote at the time that he hoped “the book would be praised by high brows and can be read by low brows. There is no writing in it that anybody with a high school education cannot read.” Cushman said in contrast, at that time there was this “cult of difficulty” of Anglo-Irish-American high modernism writers, including James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, William Faulkner and e.e. cummings.

Although the documentary was years in the making, one topic that makes Hemingway relevant today is the blurring of gender and gender swapping – in his work as well as in his life. Cushman said this is not well-known by average readers and viewers. Letters and later work contrast Hemingway’s hyper-masculine image with someone softer, willing to consider feminine traits.

“Now we know Hemingway in fact was years ahead of his time on nonbinary gender fluidity,” Cushman said.

He remembered having a pivotal discussion with Novick and producer Sarah Botstein on the subject of Hemingway in fall 2016. He met with the two when they visited Charlottesville for the Virginia Film Festival to show clips from the 10-part documentary on Vietnam. (Cushman went on to teach a University Seminar using the series in the fall of 2017, and Novick visited his class.)

It would take several years and more conversations with Cushman – who is one of 13 program advisers, a varied group of writers and scholars who appear on screen – until the filmmakers finished the documentary.

Cushman, the Robert C. Taylor Professor of English, who joined the UVA faculty in 1982, has written and edited more than a dozen books on diverse topics from the Civil War to American poetry, including publishing six volumes of his own poems. A new book of poems is forthcoming in 2022 and a book about the Civil War will be published later this year, as well as a collection of essays co-edited with UVA history professor emeritus Gary W. Gallagher.