James Loeffler followed his musical muse to become an award-winning historian.

“I started out as a jazz pianist,” said Loeffler, the Jay Berkowitz Professor of Jewish History in the University of Virginia’s Corcoran Department of History. “I grew up in Washington, D.C., and I was playing jazz piano as a teenager, and I was fascinated by the music and I thought, ‘Isn’t it interesting that the African American community has engendered this whole new art form that has become an American tradition. Where is the Jewish equivalent of this?’”

A rabbi gave him a book about klezmer, a Jewish folk music tradition from Eastern Europe. And by the time he got to college, he was fascinated and intrigued by the lost musical world.

“For centuries, Jews supplied much of the soundtrack of life in Eastern Europe – for their own communities and many others. Over time, East Europeans came to think about Jewish music the way Americans think about jazz. It became a common cultural property and a distinctive, expressive tradition that appealed beyond borders. I learned about it and I was so fascinated by how a music that defined so much of Jewish cultural life largely disappeared in America.

“By then, my quest for answers had led me down the rabbit hole of Jewish history.”

Loeffler’s passion drove him to learn Yiddish, Hebrew, Russian and several other languages. He moved to Israel after college and later studied in Russia and Ukraine, where he discovered musical manuscripts untouched since before the Russian Revolution.

“For decades and decades, this material was cut off from us because of the Cold War and the Soviet Union’s anti-Semitism,” Loeffler said. “So much of the Jewish cultural history of what existed there before the Holocaust, you couldn’t access it. Suddenly, with the end of the Cold War, it became possible to fill in the blank spots on the historical map of Jewish culture in Eastern Europe.”

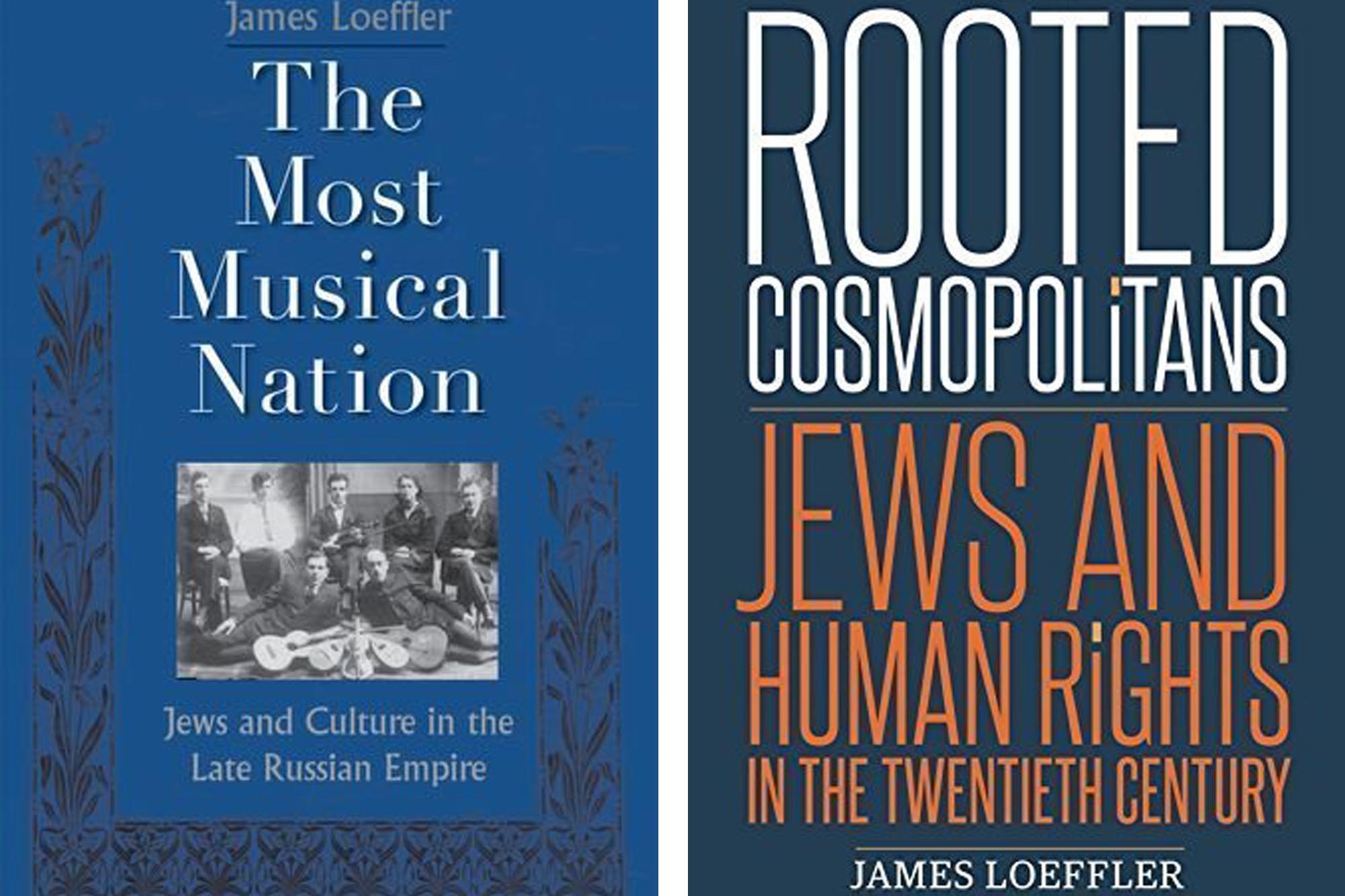

Loeffler’s interest in music and history led to his first book, “The Most Musical Nation: Jews and Culture in the Late Russian Empire,” exploring the lost world of Jewish composers working in Russia before the Bolshevik Revolution. The book won eight major awards and honors.

Since then, he has written “Rooted Cosmopolitans: Jews and Human Rights in the Twentieth Century,” about a small group of Jewish lawyers and activists from around the world he said inspired the international human rights movement, and “The Law of Strangers: Jewish Lawyers and International Law in the Twentieth Century,” about Jewish legal thinkers and lawyers and their role in making international law.

“Rooted Cosmopolitans” recently won the 2019 American Historical Association Rosenberg Prize for best book in the field of Jewish history and the 2019 Association for Jewish Studies Schnitzer Award for best book in Jewish Studies in the category of modern Jewish history.

Capping those honors, Loeffler recently was named a fellow of the American Academy for Jewish Research, which places him among the top 75 scholars in the field.

“I have the honor to join the distinguished company of senior scholars who shape the field of Jewish studies through our research,” Loeffler said of his election to the organization, often described as a Who’s Who of top Jewish studies scholars. “It was started 100 years ago, and it aims to do what I try to do all the time, which is to integrate the study and teaching of Jewish studies, broadly defined, into the University. So I’m grateful for the recognition and the exposure it affords our Jewish Studies Program.”

Loeffler teaches in the program, a free-standing, interdepartmental program in the College of Arts & Sciences that draws faculty from religious studies, anthropology, history and other disciplines. He said his being a fellow gives him a greater opportunity to influence the discipline and discuss the field with his peers in other top-flight institutions.

“The AAJR disperses scholarships and grants to students and to other Jewish studies programs, so this new role allows me to tangibly support emerging scholars and actively shape the direction of the field,” Loeffler said. “Joining this fellowship provides me the opportunity to step back and ask, ‘What do we want for our field as a whole?’ and ‘Where does the research need to go to advance the field?’”

Loeffler said the discipline has evolved over the past half-century, expanding from a subject taught primarily in American divinity schools to a diverse field that includes the study of language, literature, culture, politics and history.

Loeffler’s research has focused on Jewish studies, including culture and music.

“What began as a field focused on explaining the religion of Judaism to the modern world, and exploring the roots of Christianity, has grown dramatically into a diverse scholarly enterprise that surveys the global Jewish experience and its impact on a global scale,” he said. “At UVA, we draw on faculty from across a huge variety of disciplines and we teach the broad meaning of the subject to all kinds of different students – some of whom are interested in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, some of whom want to study the American immigrant experience, and others of whom want to know more about the Holocaust and the history of genocide.”

Understanding the Holocaust remains important to Jewish studies.

“The Holocaust is still an event that perplexes and disturbs and confounds people,” Loeffler said. “It remains a touchstone for our ethical reasoning and a history by which we make sense of many subsequent forms of global atrocity and injustice. As a result, students today remain eager to learn both about its origins and its consequences, including its ripple effects into the contemporary Middle East, American society and beyond. Jewish studies provides those answers.”

He said that Jewish studies are important to the nation because of an increase in anti-Semitism in the United States.

“I am writing a book about American anti-Semitism, because it’s a puzzle we have yet to fully explain in the history of this country,” he said. “Many students today wonder why anti-Semitism flares up on both the contemporary political right and the left. They struggle to make sense of the images of white supremacists who showed up in Charlottesville shouting about Jews ‘replacing us,’ while also complimenting Israel as a model.

“Anti-Semitism is not the same thing as racism. It is not just religious intolerance. It’s a complex form of hatred that offers a distorted mirror image of the society that produces it. So when we study anti-Semitism, we are really also looking in the mirror to see our own fears, anxieties and biases twisted into a demonic ideology of hate. To advance as a country, we will need to grapple with the sources and meanings of anti-Semitism.”

Claudrena Harold, chair of the history department, praised Loeffler as a brilliant scholar, wonderful colleague and a highly regarded teacher.

“His research in Jewish, international and human rights history has been groundbreaking and he has been the recipient of numerous book prizes and awards,” Harold said. “Jim is an intellectual fully engaged in the world, whose writings have addressed some of the critical political and ethical issues of our moment. In ways seen and unseen, he has enhanced our department’s collective efforts to share our research with various constituents on Grounds and beyond.”

For Loeffler, the pursuit of history is unending, with one thing leading to another.

“The questions never really go away,” he said. “You get into something, wanting to master it, to know it, to make better sense of the world. The question is there to be answered, and in one sense you supply the answer and then you move on to new topics.

“But the longer I go, the more I find what I really love is the questions themselves. That is also why I like teaching and researching. The questions never get fully answered. They get asked again and again. Yet in asking the questions, we discover more truths about ourselves. That is the ultimate lesson of Jewish history.”

Media Contact

Article Information

July 9, 2020

/content/faculty-spotlight-james-loeffler-musical-path-led-apex-jewish-studies