Trust is key to any partnership, but especially when your partner is slashing toward you with a drawn rapier or raised fist.

That’s exactly the situation Marianne Kubik’s students found themselves in week after week.

Kubik, an associate professor of drama at the University of Virginia, is a certified stage combat instructor with the Society of American Fight Directors. The 16 undergraduate and graduate students in her “Stage Combat Skills” course spent the spring semester learning to stage believable fights while ensuring their own safety and that of their scene partners.

They mastered staging choreographed sword fights at a whirring pace, mimicking the sound of a punch without actually landing one, and – a Hollywood classic – making a staged slap across the face seem real.

Six of the students shared some of these skills in a Facebook Live performance on Friday.

At the end of the semester, the students had the opportunity to earn recognition from the Society of American Fight Directors by performing their scenes in front of David Leong, a professor at Virginia Commonwealth University and one of 17 fight masters in the society.

The society requires that students spend at least 30 hours perfecting their skills with a particular weapon. Kubik estimates that her students spent well over 70 hours in Memorial Gymnasium learning to stage both unarmed fight scenes and scenes with rapiers and daggers.

Safety concerns are paramount. After all, even if the rapiers and daggers are slightly dulled, they are still dangerous if used improperly. And no one wants to be on the receiving end of an accidental punch.

“You really have to trust your partner,” said Kevin Minor, a graduate student in the drama department who staged an unarmed fight scene from “The Zoo Story” by Edward Albee with fellow graduate student Sam Reeder.

“I have to trust Sam to punch me in a way that will not actually hurt me,” Minor said.

“To do stage combat, you have to put yourself in danger. You have to trust yourself to protect yourself and trust your partner as well,” said Reeder, noting that Minor throws him to the ground in one of their fight sequences. “I have to be willing to put myself in that situation with someone I trust to do it safely, and for his sake, he needs to trust that I can do my job so that he does not feel guilty about hurting me.”

Every move is carefully thought through and controlled, so that each partner knows what is coming next.

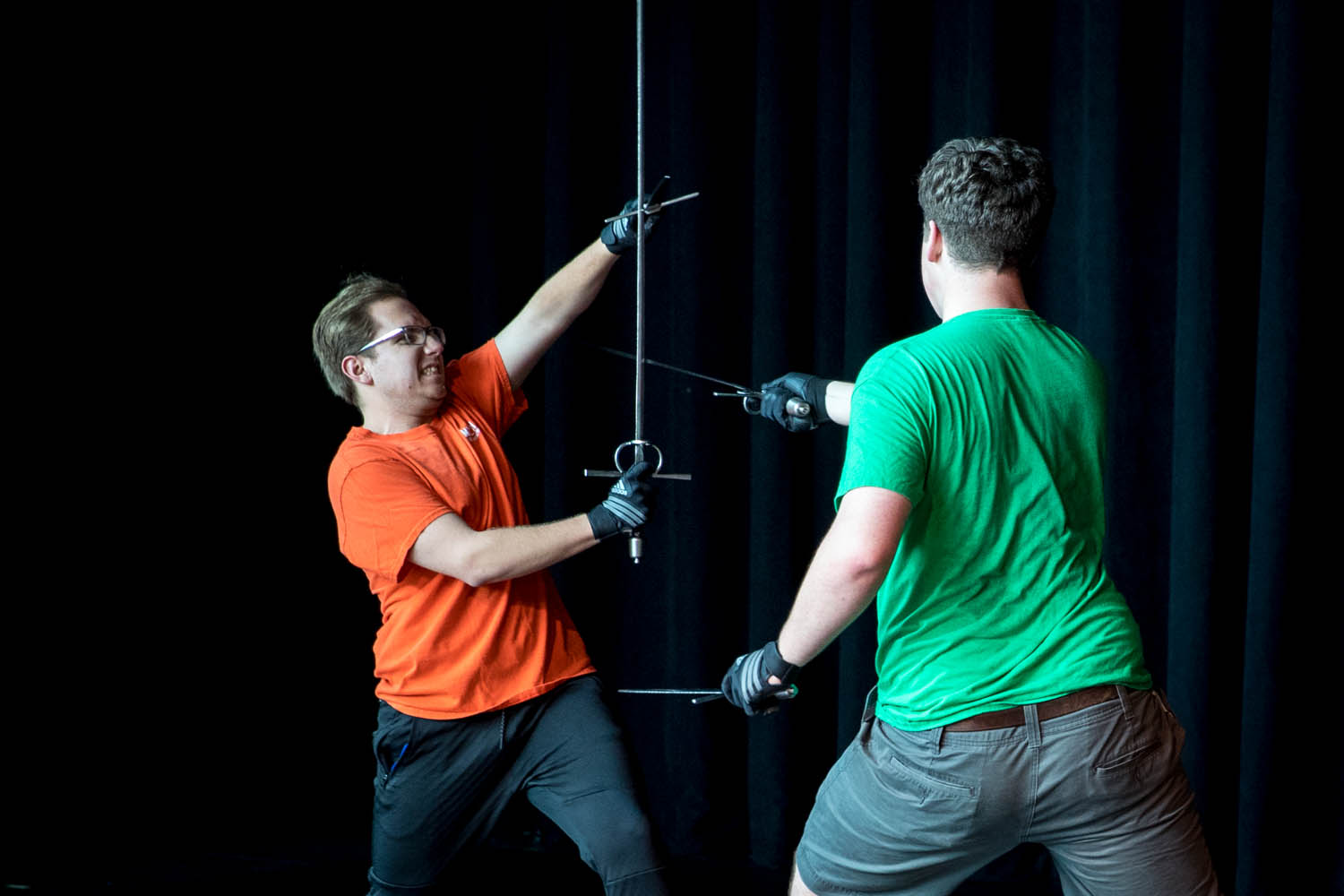

Daniel Kinsley, left, and Wes Orton staged a fight scene from “The Three Musketeers.”

“It’s a fight that is entirely under control,” fourth-year student Daniel Kinsley said. “If you lose that control, the fight can become genuinely dangerous.”

It’s also a pretty good workout.

“People might not realize that stage combat is at least as much of a workout as an actual fight,” Kinsley said.

“An added benefit – there’s no need to go to the gym,” his scene partner, third-year student Wes Orton, said.

In addition to getting in fighting shape and learning the choreography, the actors must remember to stay in character even in the midst of a tightly choreographed fight scene.

“As an actor, you have to sell the story of the fight,” fourth-year drama student Mariana González Leal said. “It’s all about how your character fits into this and sells the storyline.”

González Leal, who partnered with fellow fourth-year drama student Jessica Littman for her scenes, had no stage combat training prior to taking Kubik’s course. Littman, who had some experience, said the class was much more in depth than any training she had received before.

“A lot of times, stage combat training is kind of quick and dirty; they teach you what you need to know to do one scene,” Littman said. “This was more holistic. We knew exactly why we were doing things the way we were, both for the story and for safety.”

Having the stage combat recognition and training should help the students as they compete for roles in any number of productions, Kubik said.

“An actor has a much better chance of being cast in any production if, on their résumé, it says they have fight training or SAFD recognition,” the professor said. “Then there is no need for that sort of ‘quick and dirty’ training. They already know what they are doing.”

Kubik also said that well-executed fight scenes help make performances more emotionally powerful for the audience, offering the catharsis that can come from real-life violence without the physical risks.

“An audience can see two characters, two human beings, who are viscerally, believably violent with each other,” Kubik said. “They can have a cathartic reaction to that, and, as one of my fight master colleagues put it, we can experience that as an audience, get it out of our system and off the streets.”

Media Contact

Article Information

May 11, 2018

/content/fight-club-drama-professor-leads-16-students-stage-combat-training