The decision to admit women to study at the University of Virginia School of Law had nothing to do with administrators’ belief in equality. Instead, their hand was forced by intense social pressure, which reached an apex after women became enfranchised in 1920.

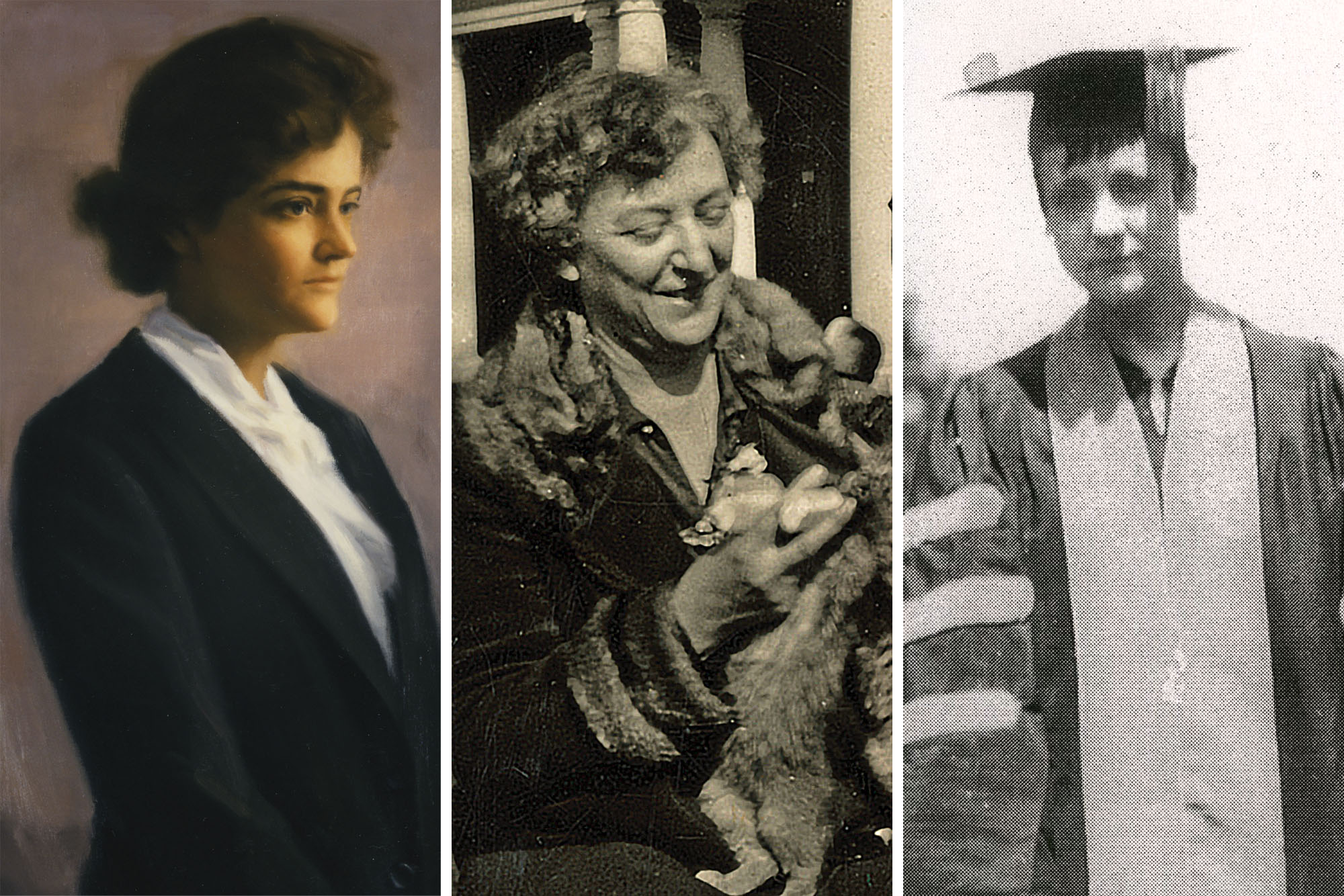

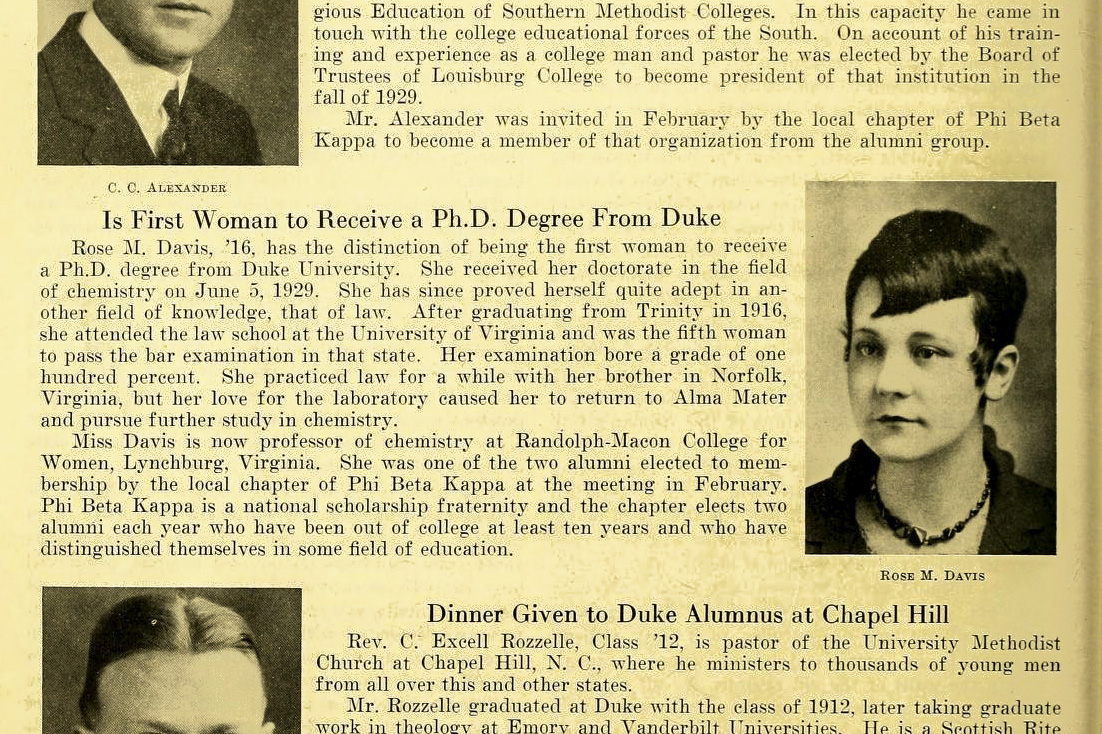

But after the Law School accepted Elizabeth Tompkins, Rose May Davis and Catherine Lipop as students, Virginia Law and its dean recognized that women could hold their own alongside their male peers, and at times even surpass them.

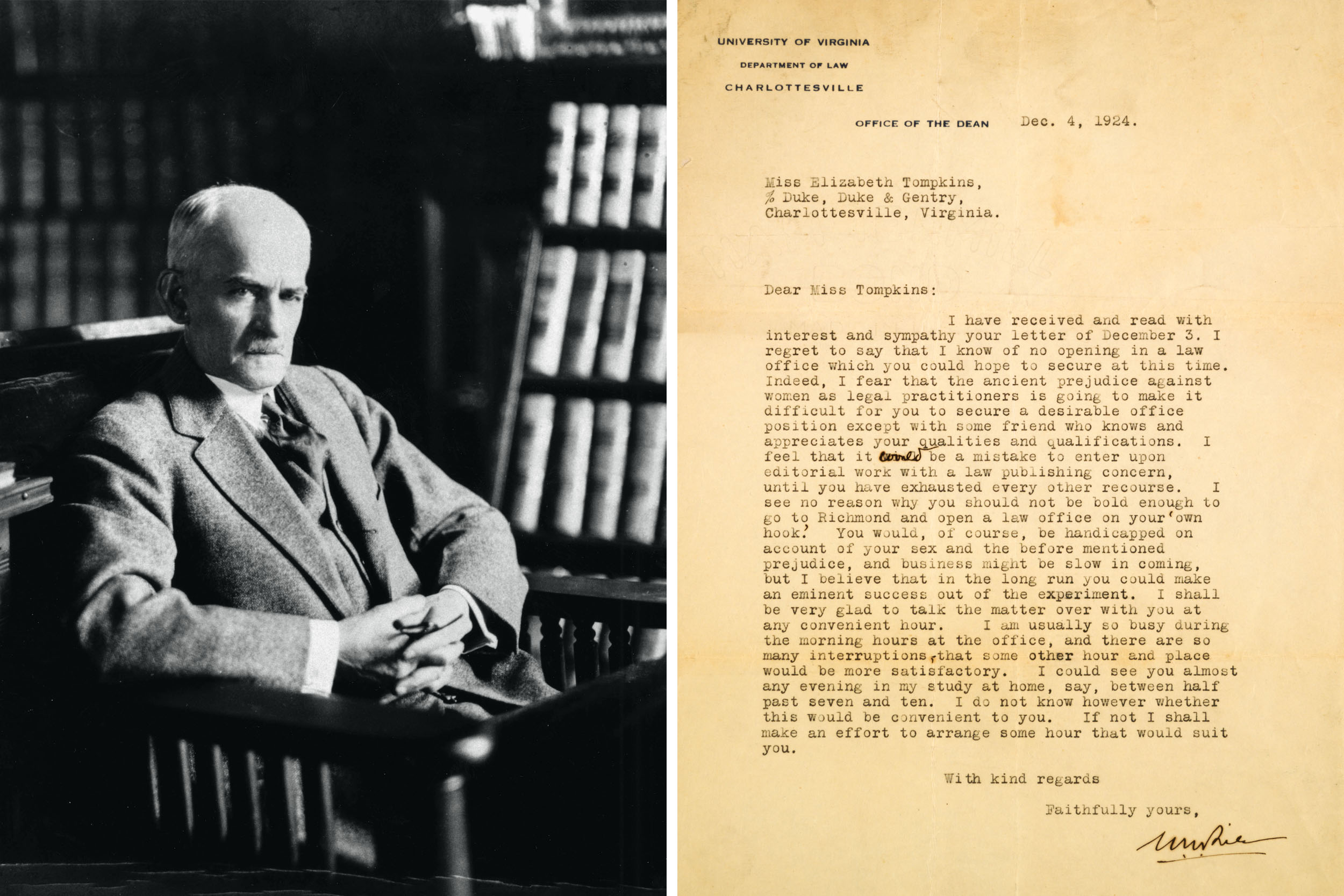

This was at odds with a belief held by many that women weren’t naturally as qualified as men to perform the lawyer’s role. The dichotomy was reflected in Dean William Minor Lile’s comments over the course of the women’s time at the Law School.

“The most important change in the organization of the Law School has been the admission of women for the first time in its history,” Lile stated in his Jan 1, 1920, annual report to UVA President Edwin A. Alderman. “The President is familiar with the circumstances which brought about this radical departure from the traditional policies of the University, as well as with the conditions under which these new and strange beings are admitted to the different departments, so I do not rehearse them here. The result is that three women are registered in the Law School this session, two as regular students and candidates for graduation, and one as a special student. Perhaps they are entitled to be immortalized by naming them in this report.”

The circumstances to which Lile referred involved, at least in part, a persuasive letter from activist Mary-Cooke Branch Munford, the first woman to sit on the Board of Visitors at the College of William & Mary. (She was among those who were instrumental in that school opening its doors to women in 1918, and became a member of the UVA Board of Visitors in 1926.)