Fourth in a series leading up to Friday's announcement of the 2015 Harrison Undergraduate Research Award winners.

After her first week as a University of Virginia student, Catherine Henry knew she wanted to be a researcher.

She’d already met with Shayne Peirce-Cottler, an associate professor of biomedical engineering in the School of Engineering and Applied Science, and discussed her interest in the biomedical engineering major earlier in the summer. The professor linked her to a fourth-year student’s project on Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and after being introduced to the lab – between navigating to classes and buying her textbooks – Henry was hooked.

“I fell in love with the research, and just kept going,” she said.

Now a third-year student, the Great Falls native has participated in four lab projects at U.Va., spent a summer researching imaging techniques in Iowa, and is a Harrison Undergraduate Research Award recipient, Rodman Scholar and Beckman Scholar. And the very first project that ignited her pursuit of research will come full circle, as she plans to make use of it as her capstone project next year.

The project involves researching the structural differences between healthy and unhealthy diaphragms – a layer of muscle at the base of the rib cage that helps draw air into the lungs – and examining how the aging process accelerates in deteriorating diaphragms. Henry’s research may help in developing a treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a devastating muscle-wasting genetic disease that results from an absence of dystrophin, a protein that helps keep muscle cells intact.

Due to progressive muscle wasting, boys born with Duchenne muscular dystrophy are bound to wheelchairs by their teens and die of respiratory problems by their mid-20s. Currently, there are no real treatments for the disease, which affects 1 in every 3,500 males (and in rare cases affects girls), despite the fact that the underlying cause, genetic mutations in the gene that encodes dystrophin, is known.

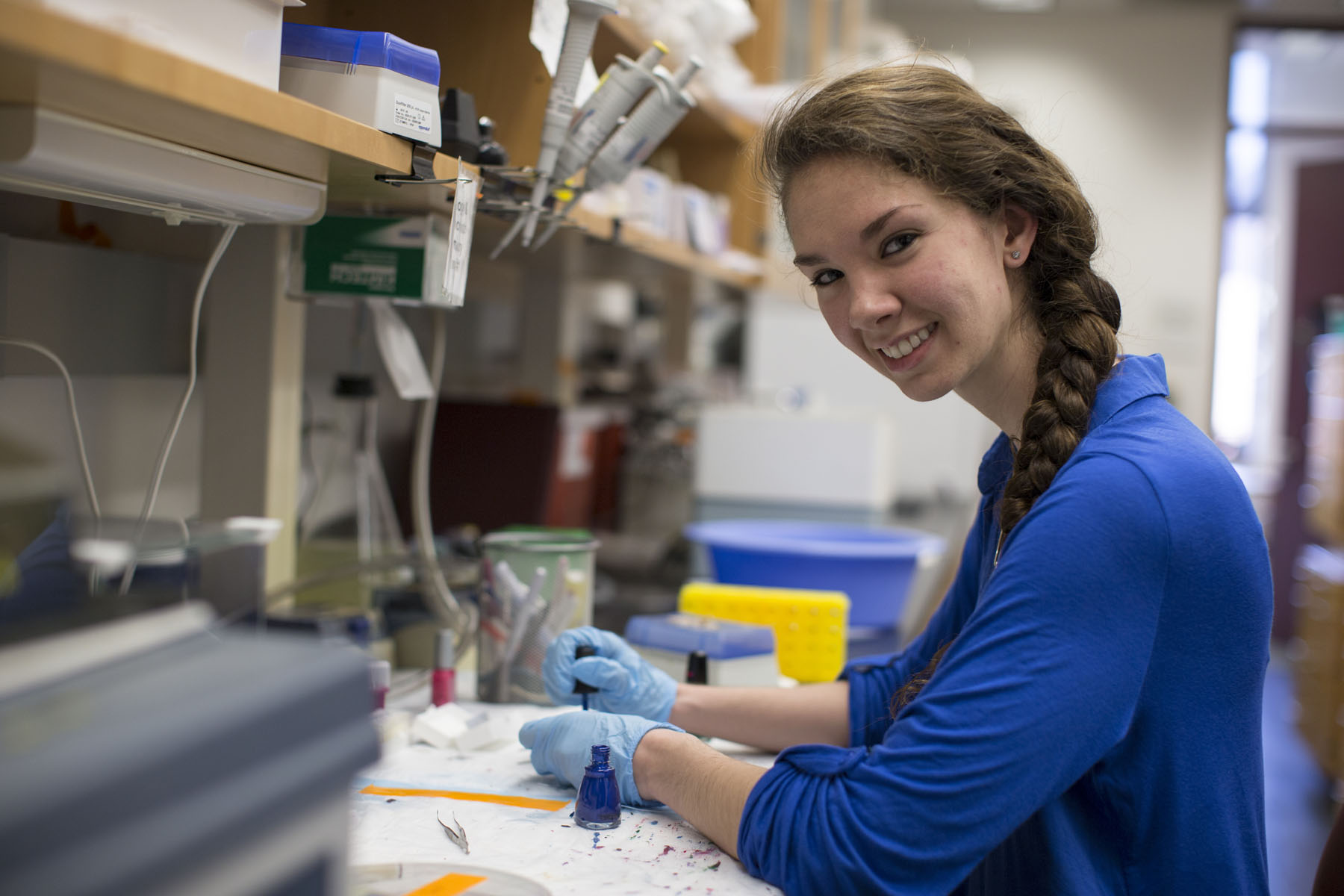

Henry spends most of her free time between classes in the lab, running tissue experiments and reading muscle scans to figure out how the shapes, sizes and patterns of muscle fibers are affected by muscular dystrophy and aging. She’ll be in the lab anywhere from a few hours to more than 40 hours per week when the work picks up.

“There’s a lot of tedious work, and things don’t work sometimes, and that’s just a fact,” she said. “But learning how to fail, and learning from those failures is so important in not getting discouraged and being like ‘OK, well, I did learn something here.’”

Cottler vividly recalls multiple Friday mornings when Henry came into lab to take microscope images at 5 a.m. so that she wouldn’t be late for her morning classes.

“Catherine’s level of enthusiasm for scientific research is among the highest I’ve ever encountered in an undergraduate student,” she said. “Anyone who has spent any time in a lab knows that some days seem to be filled with failed experiments and frustration, but on these days, she doesn’t get discouraged; she troubleshoots the problems so that the next day is filled with successes. This capability is a sign of a very mature scientist and is just one of many reasons why she is a delight to mentor.”

Under the guidance of Peirce-Cottler and Henry’s co-adviser, Silvia Blemker, an associate professor of biomedical engineering and mechanical and aerospace engineering, Henry has already submitted a scientific manuscript for peer review and presented her results at an international conference in California.

She admits that all the time spent in the lab means she hasn’t had the “typical” college experience at U.Va., but she’s found the kind of work to which she wants to devote her life.

“What drives me is just like that I’m actually making a difference,” Henry said. “Even if I find only one small thing, or I’m writing a paper about just on one small thing, someone could read that, and then read another study and like discover the cure to DMD! Even if I don’t cure the disease, if I contribute something that’s helpful and will help the next person, I’m going to be ecstatic.”

Henry wants to help other students get involved in research, too. She’s tutored others in grant writing, which she’s very good at – the Beckman Scholarship alone was $19,300 – and as the research chair of the Rodman Council, she links students to professors and lab opportunities around Grounds.

After she graduates, Henry plans to pursue graduate school, but she wants to work in a clinical setting for a year to be more directly exposed to people.

“I love biology, because I think the human body is the most interesting thing in the whole world,” she said. “I definitely want to study the body and how it functions, and for me biomedical engineering just made sense because I can directly apply what I know and make a difference.”

Media Contact

Article Information

March 25, 2015

/content/how-budding-undergraduate-scientist-found-her-calling-biomedical-lab