When Dr. Amy Mathers was a kid, she had no interest in following in the footsteps of her father and becoming a doctor. At the age of 6, she decided she wanted to study the ocean. Mathers wouldn’t waver – until she got to college.

“I was like, ‘Wait a minute, I can’t live on a boat at sea for long extended periods of time,’” Mathers said with a laugh. “I didn’t think it would be right for me.”

All these years later, Virginians – and people all around the world – should be thankful for her career epiphany.

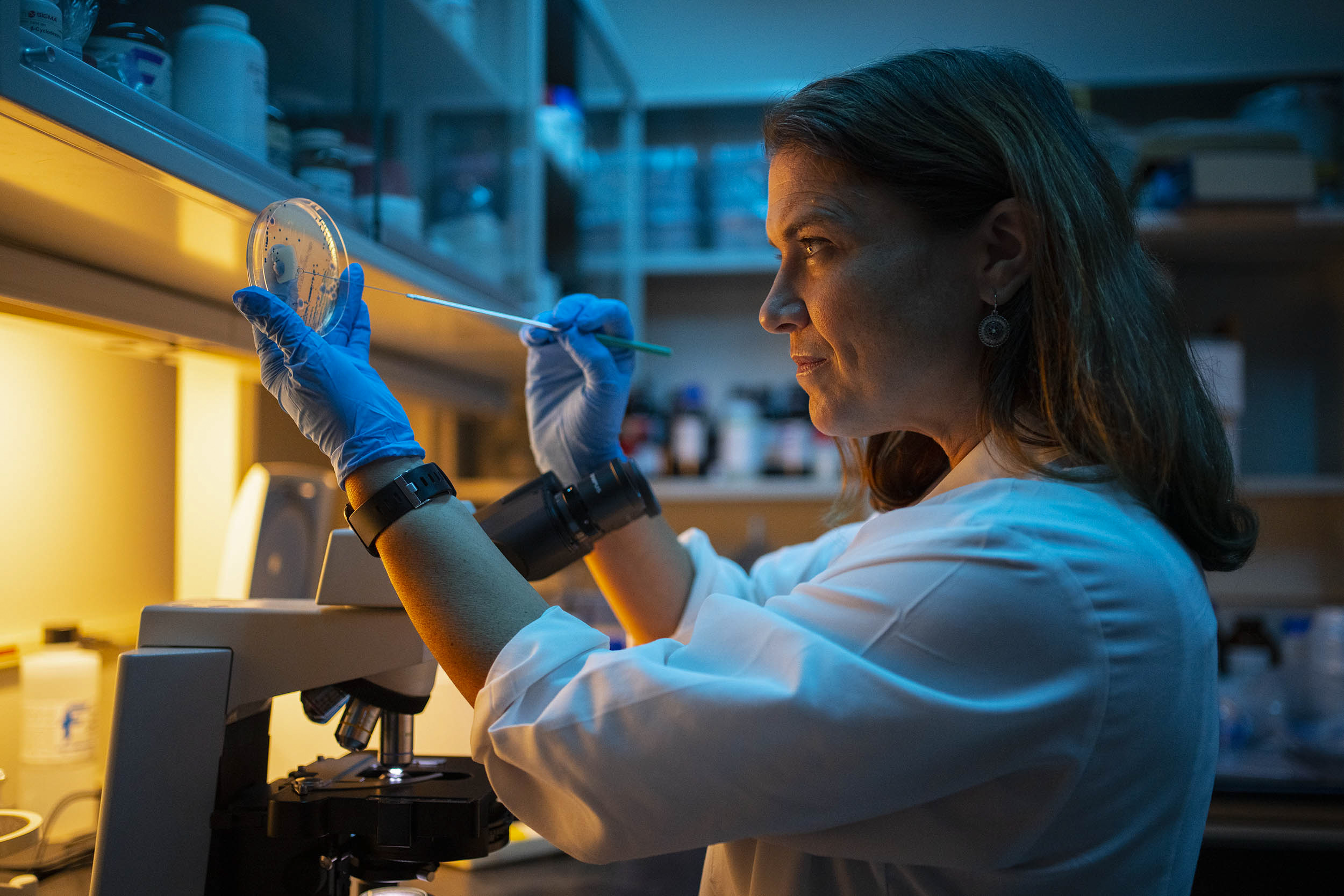

Over the last 20 or so months, Mathers, associate director of clinical microbiology and an associate professor of medicine and pathology at the University of Virginia, has been a hero.

At the beginning of the pandemic, when federal health agencies couldn’t provide enough COVID-19 tests, Mathers worked with Melinda Poulter to help create in-house tests to meet the demand at UVA and at hospitals across the state.

But she was just getting started.

When massive testing led to a nasal swab shortage, Mathers helped solve that issue, too – by helping design, manufacture and get FDA clearance so swabs could be distributed across the state to meet the shortage needs.

As the pandemic wore on and students returned to Grounds, Mathers helped develop a solution for testing wastewater from buildings to detect signs of COVID-19, thereby helping identify potential positive cases and prevent larger outbreaks.

And then, as SARS CoV-2 mutations and successful variants began to emerge, she quickly pivoted her laboratory to begin applying whole-genome sequencing to monitor emergence to inform public health policy and understand transmission.

It was for these life-saving innovations – as well as her work as the chief medical officer of Antimicrobial Resistance Services Inc., a company that specializes in whole-genome sequencing to inform and mitigate the spread of harmful bacteria – that the UVA Licensing & Ventures Group chose Mathers as the recipient of this year’s Edlich-Henderson Innovator of the Year award. The endowed award recognizes University faculty members or a team of faculty researchers whose work is making a major impact on society.