It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single person in possession of a good “Pride and Prejudice” adaptation must be in want of another one.

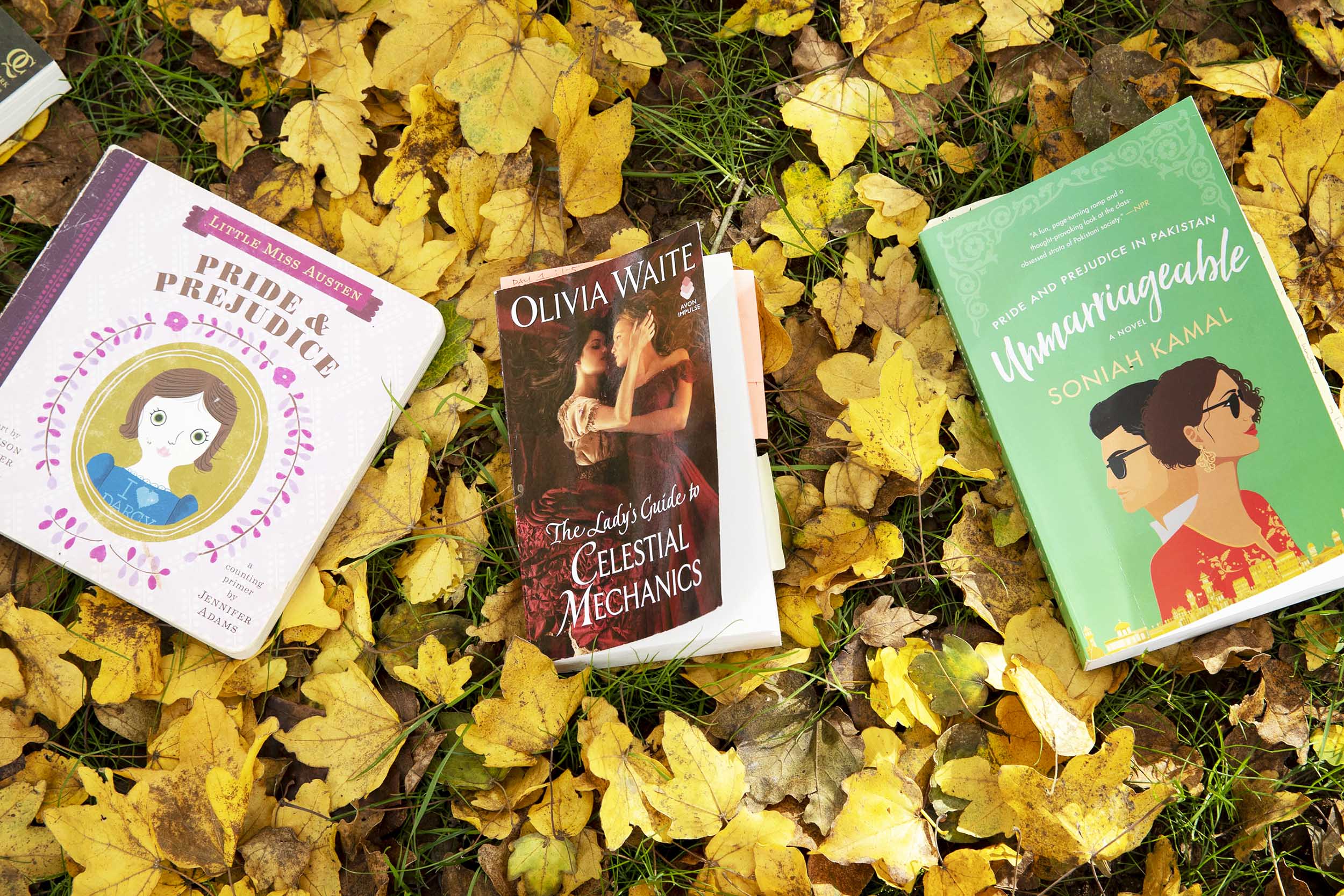

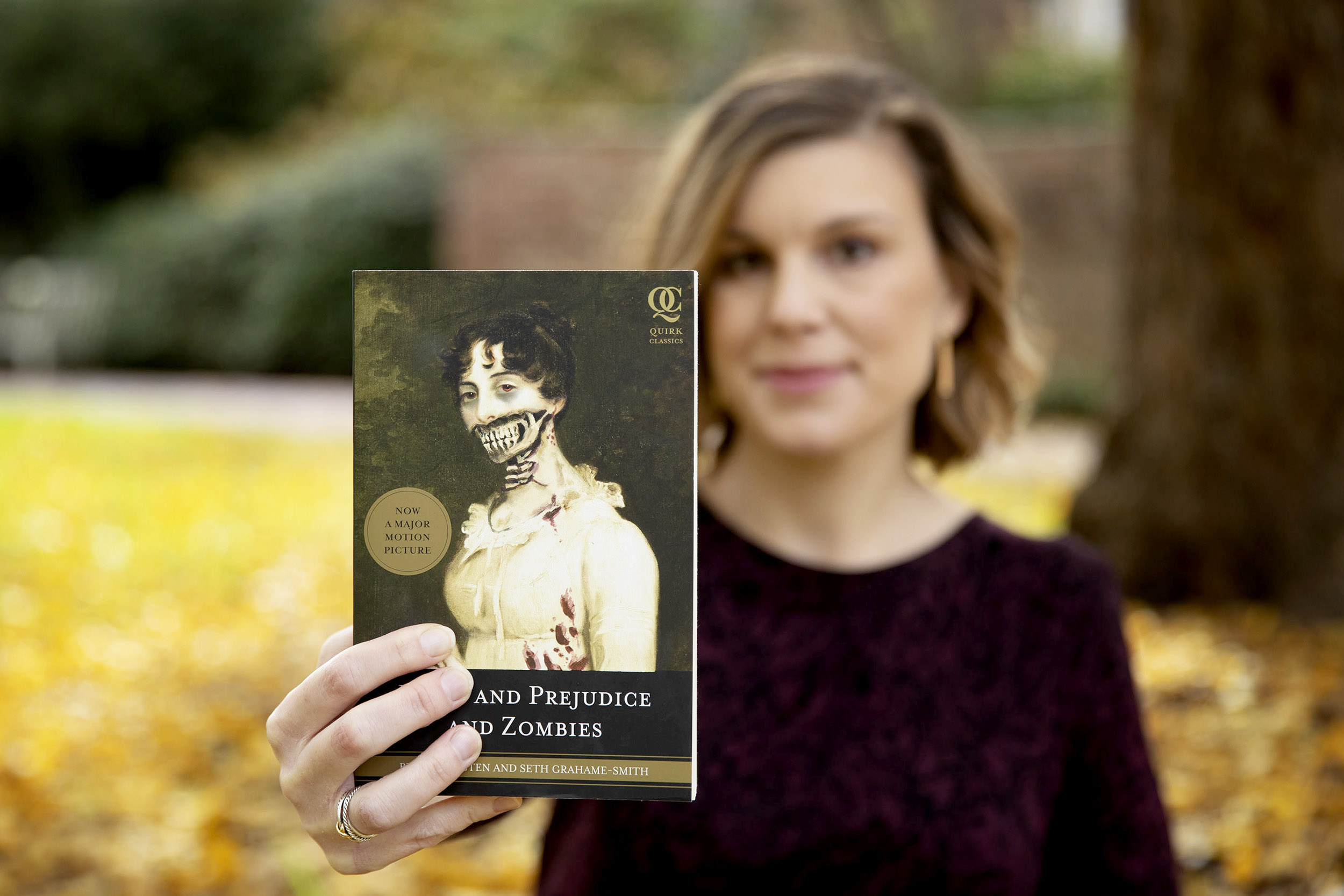

Jane Austen, who published the aforementioned novel anonymously in 1813, could not have imagined its popularity more than 200 years later. Over the past 25 years, especially, her work has enjoyed a resurgence, spawning numerous adaptations in print, television and film, with no signs of stopping, in other countries as well as America.

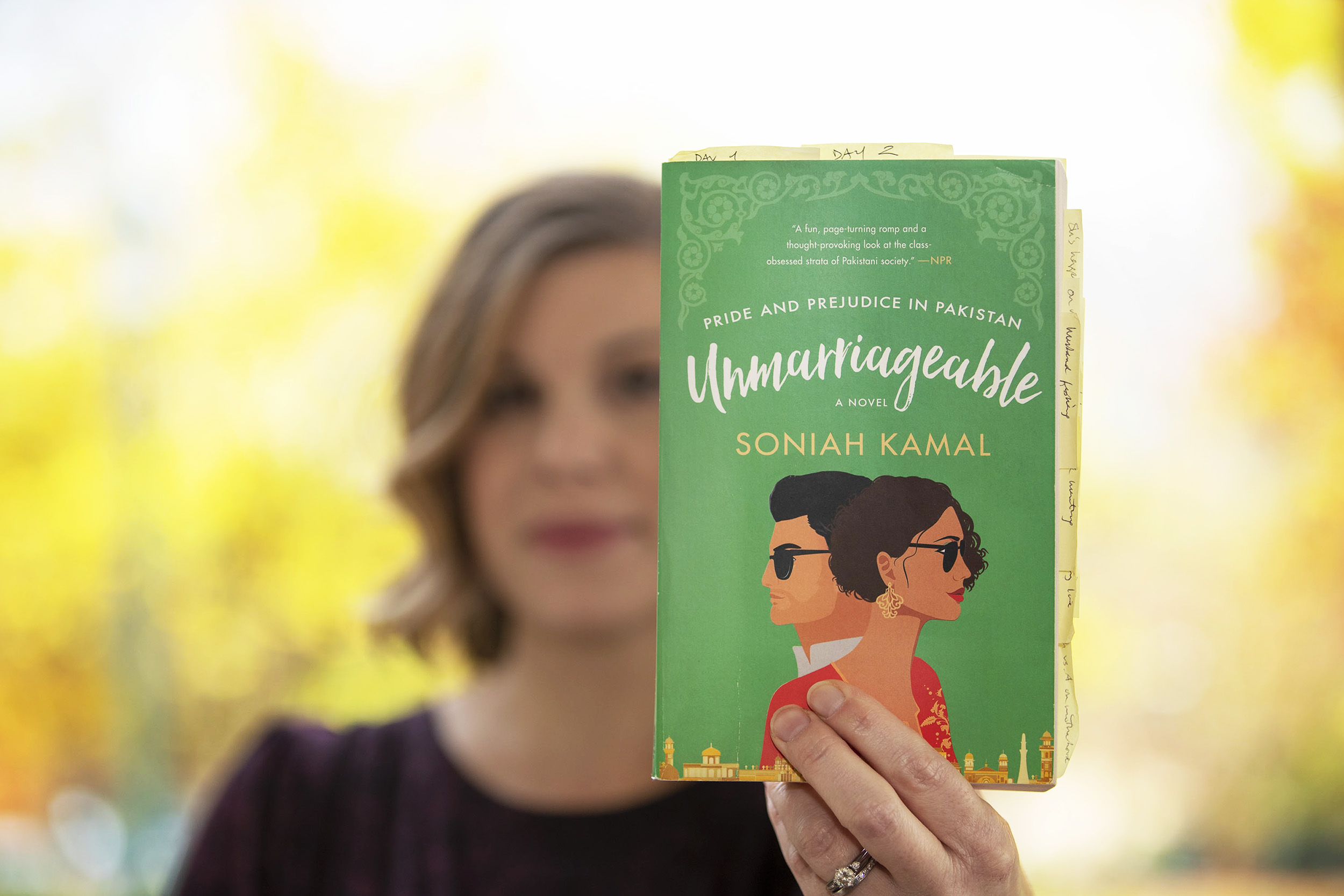

Some of the adaptations use the first sentence of “Pride and Prejudice” (reinterpreted – or mangled – above): “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.”

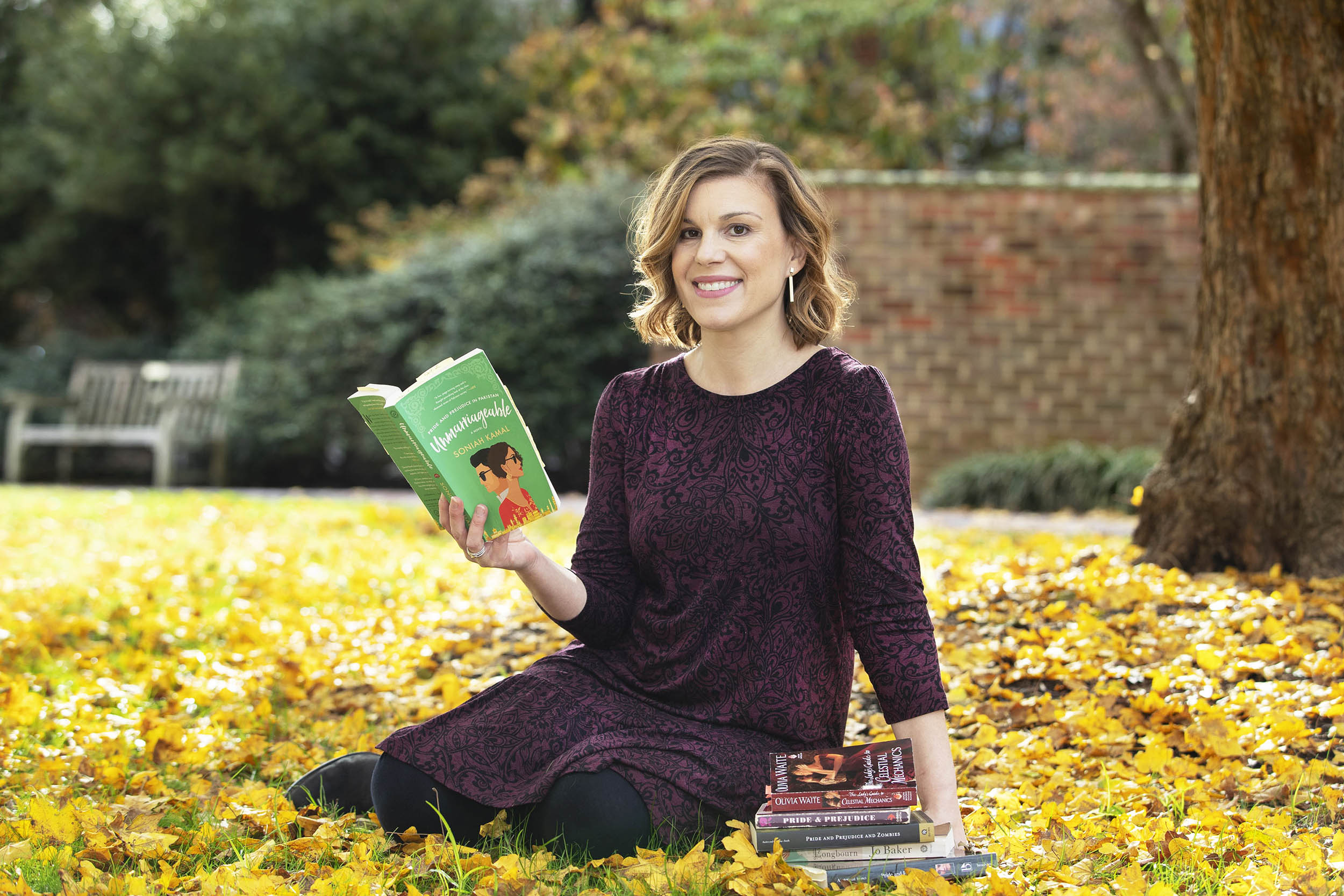

Cristina Richieri Griffin, a postdoctoral fellow in 19th-century studies in the University of Virginia’s English department, is OK with all this.

“Whatever it takes to get people to read a good book,” she joked.