In the letters, he noticed a change in the tone of the writing of his friend, who was doing time for stabbing a man who’d beaten Santana’s girlfriend, resulting in the miscarriage of her baby. “He would just ask questions every once in a while that were kind of a deeper question,” Pritchett said. Santana never did mention the name of the UVA course he was taking, and the letters faded from Pritchett’s memory until, nearly seven years later, it was time to apply to UVA.

“It wasn’t until I’d made the decision to apply to UVA that I realized, ‘Oh yeah, my friend took this class with this professor,’ and I’m worried about getting in and if there is anybody who would help me, it’s probably this professor,” Pritchett said, referring to Kaufman.

Pritchett reasoned that Kaufman would have some insight, “and he knows people like me, so he understands where I’m coming from.”

So, Pritchett reached out to Kaufman. “After we met, I was like, ‘Dude, if I get into UVA, I’m taking this class.”

Kaufman helped Pritchett hone his personal admissions essay for his McIntire application, encouraging him to be real and honest about his past. Pritchett followed that advice. This is an excerpt from his essay.

“I was raised in a challenging environment full of abuse and negative behaviors. During my teenage years I was in and out of courtrooms and juvenile facilities, due to both home life concerns from Social Services and my foolishness as a teenager. At seventeen years old my actions led me to be incarcerated for two and a half years.

“Today I have a life that I would have never thought possible before. I once believed I would be dead or incarcerated for life by age twenty-five. Today, I am twenty-five and using my life to make a difference. With an education at McIntire I hope to make an even greater one.”

In May 2017, Pritchett received word that he had been admitted to McIntire. It was then that he began the process of applying to “Books Behind Bars.”

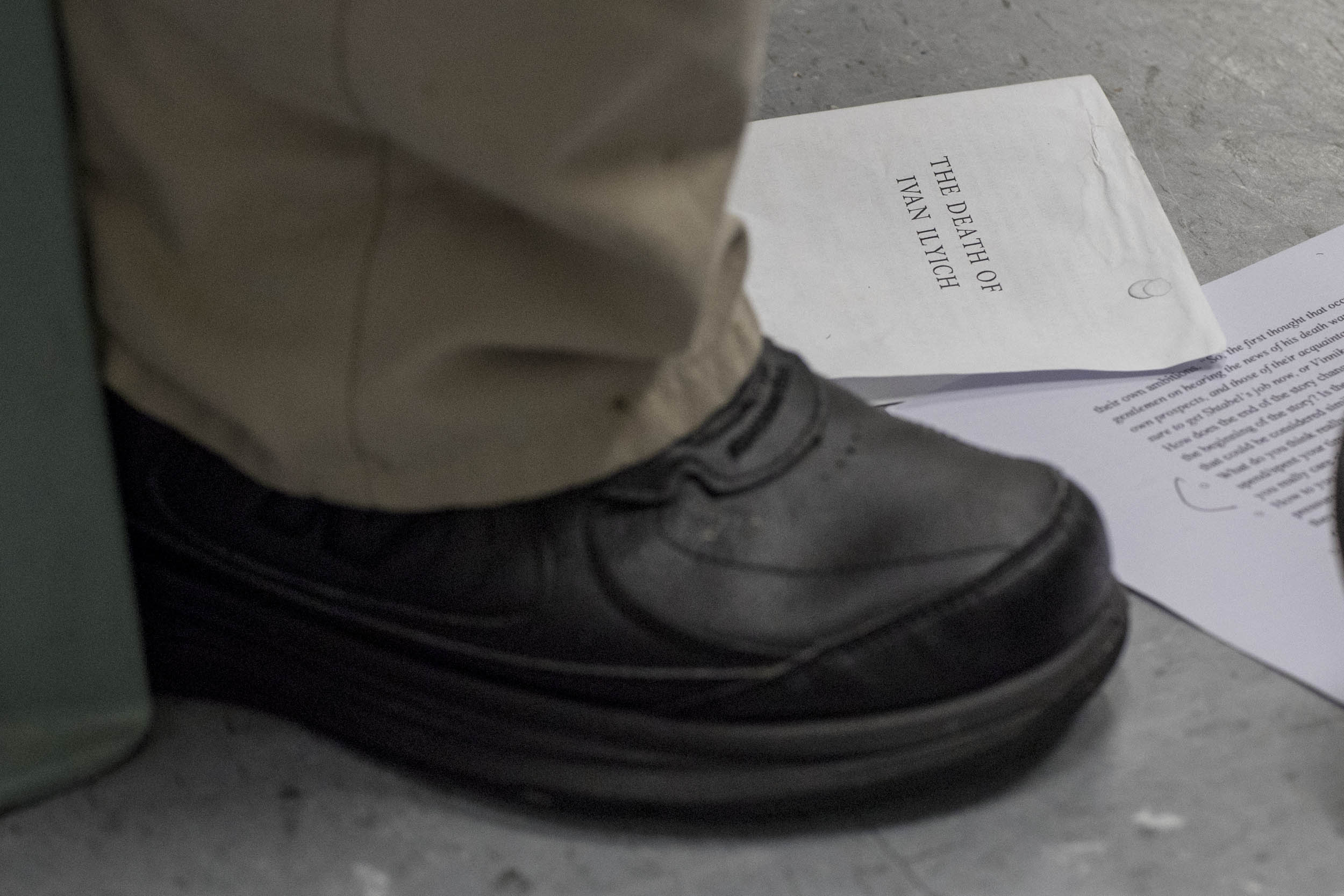

Kaufman said he was intrigued at the prospect of having a former juvenile facility resident in his class, because it would lend a new dimension. “It was important to me that he wanted to take the class itself, and not just have an opportunity to go to the facility,” he said. “After talking to him, reading his analysis of Fyodor Tyutchev’s poem, ‘Silentium,’ over email, and later, his course application, I was comfortable.”

Kaufman was right. Pritchett did bring a new dimension to the class.

‘You Could Sense a Shift in the Atmosphere’

“I never really thought of Josh as a ‘former resident,’” Kaufman said. “He was always a UVA student to me, and I wanted to make sure the other students viewed him the same way.

“Of course, I wanted to take full advantage of his unique knowledge about the world we were going into, but I was always careful not to hold him up or encourage others to hold him up as the UVA class ‘expert’ on incarceration,” Kaufman said.

It was a few weeks into the class before Pritchett shared his past with his UVA classmates. “That was scary,” he said. “I’m not one to keep my story hidden. I have no problem with being transparent.”