With the nation set to celebrate its 250th anniversary next summer, the University of Virginia’s Karsh Institute of Democracy is taking us back to the tumultuous early days, when competing political factions debated what the future of the colonies should be – and then fought a war over it.

The institute’s biennial “Democracy360” event begins Oct. 15 with a panel discussing the nation’s founding and how the political ideals and principles hatched then are playing out today. A panel conversation will follow an exclusive preview of Ken Burns’ latest documentary, “The American Revolution,” based in part on a book by UVA professor Alan Taylor, who appears in the film.

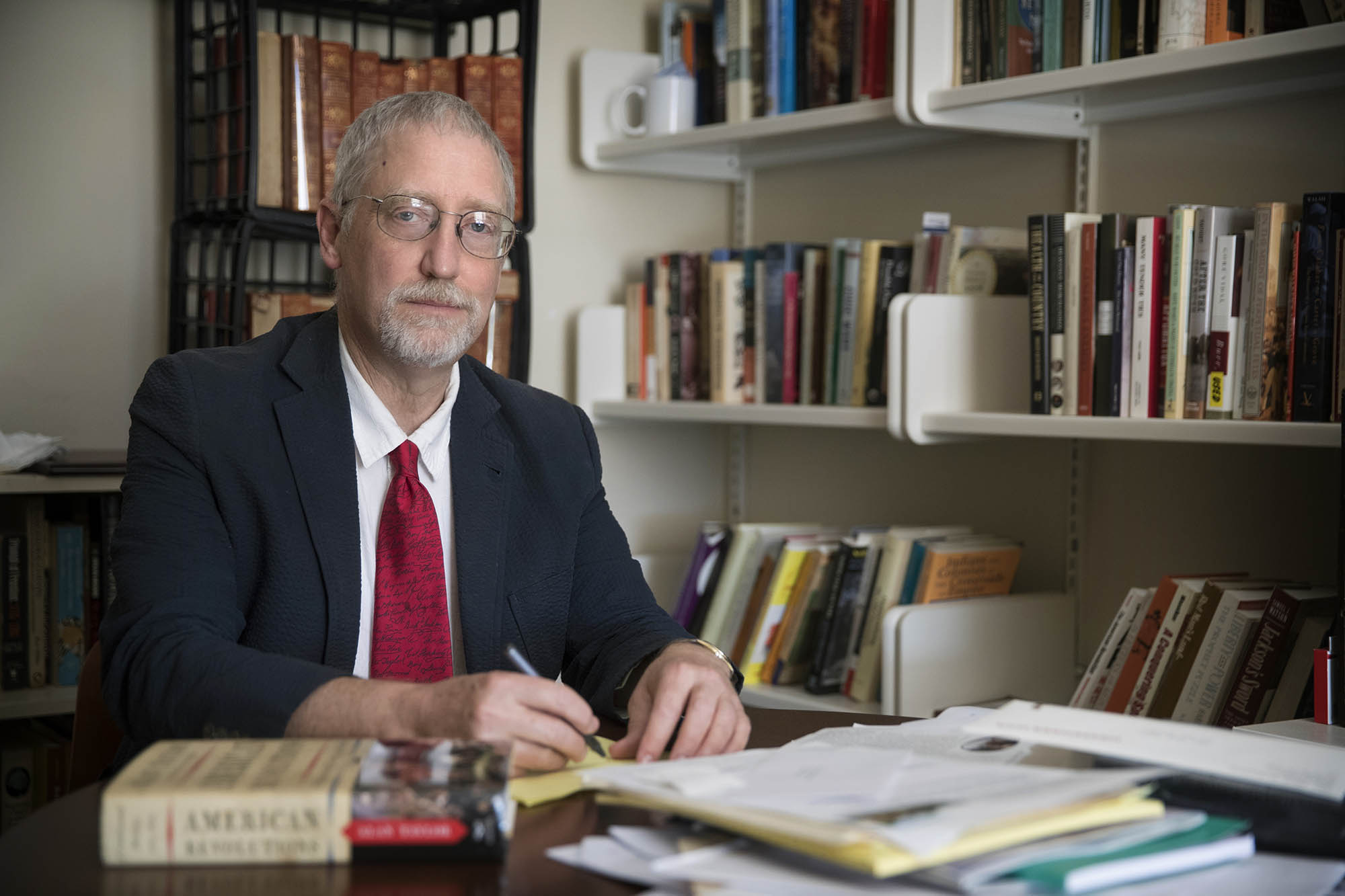

Taylor appears in the documentary and became an adviser to the producers after one of them read his book, “American Revolutions.” (Contributed photo)

The three-day event in Charlottesville will feature five mainstage programs at the Paramount Theater where national journalists, Pulitzer Prize-winning historians and bestselling authors will explore the challenges and opportunities facing democracy at this historic milestone. Democracy360 also includes participatory debates and interactive working sessions that invite attendees to engage with one another and work together on solutions to the challenges facing democracy.

The Atlantic is the event’s official media partner and VPM will distribute event video. All Democracy360 events are free and open to the public. Tickets are available through the Paramount Theater box office.

Ahead of the Democracy360 launch, Taylor chatted with UVA Today about how he came to be in the Burns’ documentary, and how the lessons of the American Revolution are still relevant today.

Q. How did you become involved with the Ken Burns documentary?

A. One of the producers, Sarah Botstein, had read my book, “American Revolutions,” and liked it, so she reached out to me about becoming one of the advisers for the film. As an admirer of Ken Burns’ films, I was honored to join that team.

Q. When the film debuts, what are you hoping modern Americans will take away from it?

A. The film offers an honest, comprehensive, sobering, yet inspiring take on a revolution that was far more contested and divisive than Americans today recognize. The film takes the Loyalist Americans seriously instead of treating them as cartoonish villains. The film also treats empathetically the plight of Native peoples caught up in that war and the contradictions of slavery in a society fighting for the freedoms for some Americans. And the film is about a revolution that generated the noblest aspirations for people to govern themselves free from kings and tyrants.