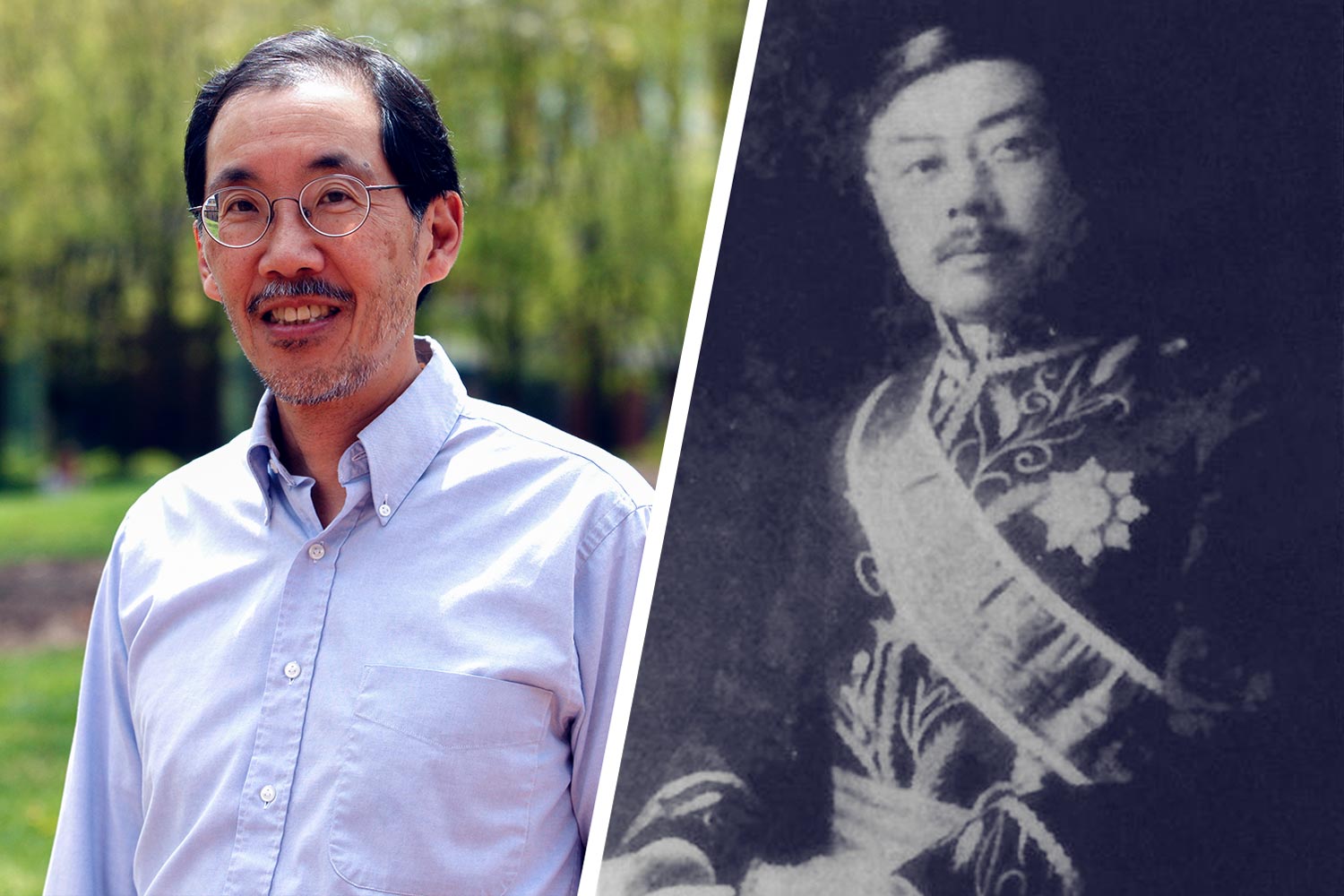

University of Virginia law professor George Yin, an expert in tax policy, has a keen interest in history, including his own family tree. But one family connection he learned about this year came as a shocker that could easily have been an episode of “Finding Your Roots” or “History Detectives.”

Yin learned that he is related to the late Chinese statesman W.W. Yen, who was UVA’s first Chinese graduate and the first international student to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree from UVA. The law professor is a grand-nephew of Yen.

The revelation came as part of a planned dedication of a dormitory in UVA’s International Residential College. The University chose last year to rename the former Lewis House as the W.W. Yen House. The official dedication will take place Friday, and Yin will be there.

UVA’s Board of Visitors agreed to rename Lewis House at its meeting in September, with a resolution calling Yen a “highly accomplished diplomat.” (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

“It’s really been a fascinating couple of months,” Yin said. “Once UVA announced the dedication, the school, of course, got word to immediate family and invited them to spread the word to more distant relatives. In that process, the announcement eventually filtered over to me.”

If this were one of those family history programs, here’s where the narrator would ask: “Who exactly was W.W. Yen? How did he end up at UVA? And how was the link to Professor Yin established?”

Weiching Williams Yen, aka Yan Huiqing, was China’s first ambassador to the Soviet Union and a delegate to the League of Nations. Yen later served multiple times as China’s foreign minister and prime minister, and was briefly his country’s acting president.

He was also an educator who was influential in the founding and establishment of Tsinghua University in Beijing (whose campus design has a close resemblance to Grounds), as well as the author of an innovative English-Chinese dictionary.

The Grand Auditorium at Beijing’s Tsinghua University, a school which W.W. Yen helped found, appears to be modeled on the University of Virginia’s Rotunda.

But before Yen went on to become a distinguished public servant and educator, he came to Virginia to learn.

Through his father’s connections at the missionary-founded St. John’s College in Shanghai, Yen relocated to Virginia in 1895. He attended Episcopal High School in Alexandria. Following some special tutoring in Latin, he enrolled at UVA in 1897.

He received his bachelor’s degree from the University on June 13, 1900.

Given Yen’s UVA connection and considerable historical prominence, how could a Virginia law professor attuned to his own lineage have missed the link?

Yin’s family originates from Shanghai, but time, distance and the language barrier have all contributed to a lessened connection with the old world.

It was only thanks to the upcoming event that Yin received the surprising news, which came via one of his first cousins, Julian Suez.

“Julian had received an invitation from one of his relatives and made the connection with me and UVA,” Yin recounted. “At that point, I said, ‘What’s going on here?’”

The professor donned his history detective hat. His investigation revealed the reasons behind the previously unknown relationship.

“Julian’s mother and my mother were sisters, less than a year apart, so they were very close,” Yin said. “I was also close to his mother. But as it turns out, Julian’s connection with the Yens is through his father, whom I never met. His father didn’t travel to the U.S. after I was born, and I never went to China until fairly recently, long after his father had passed away. So I never had the chance to just sit around after dinner and ask his father about his background and family. And others who knew him never spoke to me about him.”

Yin explained that Chinese custom treats “family” broadly to include relations through both blood and marriage, but distinguishes family members by their generation.

Therefore, “By Chinese custom, I would be considered a grand-nephew of Yen,” he said.

Yin wanted to learn more about his famous relative. He discovered and read Yen’s autobiography, “East-West Kaleidoscope 1877-1944,” in which the world figure details his life in public service and education.

Yin has his own history in government. Among his roles, he served as chief of staff of the U.S. Congress’ Joint Committee on Taxation, one of the most influential tax positions in the country. Yin is also an educator. Early in his career he taught elementary school and directed a child care center. He began teaching law in 1986, and has been at the University since 1994.

He said he was fascinated to read details of his relative’s UVA education in “Kaleidoscope.”

Yen was one of very few international students at the time, and the bachelor’s program was loose, with students selecting classes based more on interest than regimen. Yen describes taking an extra Law School course, “International and Constitutional Law,” which, he writes, proved useful to him in his subsequent diplomatic career. Overall, his classes presented varying levels of challenge. He enjoyed the ones lumped broadly under “philosophy” the most.

Yen speaks highly of living in Charlottesville, which included moments of hospitality and diversion in the relatively rural setting. He recalls some of his undergraduate classmates as aloof or focused on their work, but suggests that their lack of closeness wasn’t anything personal toward him, but rather followed from their lack of a common curriculum.

“It is believed that among the law and medical students there was a greater measure of comradeship and friendly association, for the reason that they were thrown together on more occasions and during a longer period,” he writes.

In Yen’s final year at UVA, the University refunded his tuition. The gesture was a source of pride for the foreign student.

“The last year at college the Chairman of the Faculty (in those days there was no President) was kind enough to remit my tuition fee,” he writes. “He said, ‘You have been so long in our state that we can consider you a Virginian.’”

Yin said he believes the courtesy was an indicator of the esteem with which the student was held.

“They obviously accepted him and felt he fit in fine,” Yin said. “My guess is that it took him a little while to feel fully integrated with the rest of the University.”

In researching his newfound relative, the law professor was struck by the timing of Yen’s opportunities. Yen came of professional age and was able to utilize his Western education to serve his country soon after the collapse of the Manchu Dynasty in 1911.

“He took a lot of initiative, but he also had some very good fortune,” Yin said. “There weren’t a lot of young Chinese people who had his kind of education, language skills and experience at that moment of great national need.

“He did a lot to achieve his many accomplishments, but he also had a lot of help to get to where he was when the opportunities arose.”

As Yin delved into the new, untapped vein of family history, he learned about additional relatives.

He recently met and befriended current fourth-year undergraduate student Diana Yen, a more direct relative of Yen. Her paternal great-grandfather was Yen’s first cousin. She is pursuing a degree in economics and politics.

Yin also discovered yet another relative in UVA’s past.

Yen was preceded at the University by Theodore T.T. Wong, who attended from 1894 to 1897. Wong was UVA’s first Chinese student and knew Yen. Wong, however, transferred to Georgetown University before graduating and obtained his degree from that school, making Yen the first international and Chinese graduate at UVA.

“I discovered that I have an even closer relationship to Wong,” Yin said. “He was the grandfather of another first cousin of mine.”

Wong’s life – and death – were also of historical note. Wong was involved in both education and publishing, and eventually became head of Overseas Students in America, based in Washington, D.C. In that capacity, he was killed in 1919 by a disgruntled Chinese student. The student was convicted and sentenced to death, but his conviction was overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court in Ziang Sung Wan v. U.S. in 1924, based on the court’s conclusion that the defendant’s confession was inadmissible evidence. The case was one of the precedents that led to Miranda v. Arizona years later, requiring that arrestees be informed of their constitutional right against self-incrimination.

Media Contact

Article Information

April 10, 2018

/content/law-professor-finds-unexpected-family-ties-world-figure-uvas-past