Editor's note: This story was originally published on July 27, 2015.

If you Google the words “Tsinghua University Rotunda,” a collection of publications will tell you this: The Grand Auditorium at the famous Beijing school is modeled on the University of Virginia’s iconic Rotunda.

But finding out exactly how the Chinese building came to look so much like its doppelganger in Charlottesville is not so easy. There’s no clear answer, but the building’s origins may involve the University’s first Chinese graduate, a member of the Class of 1900 who would later go on to serve as China’s premier and briefly as the country’s acting president.

This is how Tsinghua University architecture professor Yishi Liu described his university’s rotunda in a recent research paper: “Regarding the central part of Tsinghua that includes the Auditorium, the lawn and flanking buildings, it is well-known that the Auditorium is a reduced imitation of the Rotunda of the University of Virginia, and the planning of the area a derivation from Academical Village [sic]. However, it remains largely unknown how or whether the two campuses are connected.”

Some connections are obvious: UVA enjoys a fruitful relationship with Tsinghua University and has an exchange program with the school. But the similar architecture is a bit of a mystery.

Some background: schools that went up in China in the 20th century were often made to look like universities in the United States (which in turn had looked to Europe for their architectural inspiration, though that’s another story.)

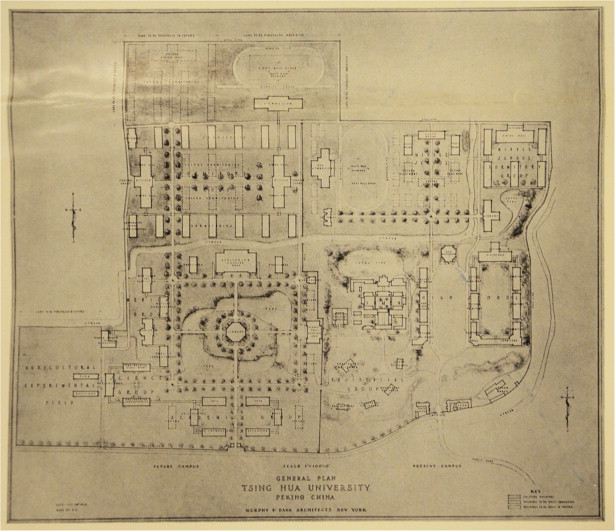

In 1914, President Zhou Yichun of Tsinghua, then a training school, tapped his former Yale University classmate and great American architect Henry K. Murphy to draw up the plans for what would become a full-fledged university. As Liu writes, Murphy’s original drawings are striking in their resemblance to Grounds.

Campus planning scheme by Murphy in 1914. Source: Murphy Papers. MS 231-Box 4, Folder 4.

“The plan produced by Murphy later is an imitation of the specific form of Jefferson’s design – key elements including a mall lined with buildings arranged along both sides that defined a longitudinal axis, and a central structure as a focal point an extended rectangular space – became an emblem of the school’s landscape, and began to exert a great influence on modern Chinese college planning,” he writes.

“Jefferson’s educational ideal was in fact largely American in spirit, and echoed the principles of other educators of the period in its collegiate commitment, its familial overtones, and its desire to withdraw from the life of cities and be a ‘village’ unto itself, rather than being isolated from the outside world as in England, and such ideas became the touchstone for the campus planning of Tsinghua too.”

Liu also notes that the infamous fire that damaged Jefferson’s Rotunda in 1895, followed by Stanford White’s remodeling of it, brought UVA's Grounds into the national news and helped to popularize its design.

In the end, Tsinghua erected its own rotunda but without two lines of buildings bordering its mall.

UVA and Tsinghua share some early links that make this story decidedly more interesting, and they come in the name of Yan Huiqing, the first student from China to graduate with a titled degree from UVA.

Yan graduated with a B.A. in 1900 after attending Episcopal High School in Alexandria, Virginia, for two years. He returned to Shanghai and for the next several years taught English and wrote and edited works including an Anglo-Chinese dictionary.

According to the Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity, Yan’s trajectory changed following China’s Republican revolution of 1911, when young officials with Western training were placed on the fast track for promotion. “Yan Huiqing was catapulted to the position of Vice Minister and Counselor. Due to the poor health of the foreign minister, Yan usually briefed President Yuan Shikai each morning and accompanied him in meetings with foreign diplomats.”

Yan, whose English name is Wei Ching Williams or W.W. Yen [sic], was appointed vice minister of foreign affairs in 1912 and named acting supervisor of what was then Tsinghua College in January of that year.

Tsinghua President Zhou proposed the design for the future of the school to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1916, where Yan, who was to become foreign affairs minister, no doubt had influence.

There is no proof that the UVA graduate determined the design of Tsinghua’s rotunda, but his influence is possible - perhaps even likely – and it’s certain that he helped to form the institution that would become Tsinghua University. There is also evidence that he had an influence on appointing some of the institution’s early leaders.

Yan’s political career did not stop at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He served as Premier of the Republic of China five times and simultaneously as acting President on his last premiership in 1926. He was also China's first ambassador to the Soviet Union and a delegate in the League of Nations.

In his later years, he published his memoirs, "East-West Kaleidoscope, 1877-1946," which includes some of his experiences at UVA. A UVA student-run Chinese language magazine, V-ke, includes the following excerpt:

“Visiting Monticello, the home of Thomas Jefferson, founder of the University, driving into the surrounding beautiful country in buggies or riding on bicycles, going to the hotel at Frye Springs, …, going to see a show at the only theatre on Main Street (there were no ‘pictures’ in those days), almost daily walks downtown, and on Sundays attending various churches, Episcopalian, Presbyterian, Baptist, Methodist, and even once Roman Catholic, were the principal diversions of our college days, outside of social visits.”

Following her first trip to China in 2012, President Teresa A. Sullivan asked UVA historian Alexander G. “Sandy” Gilliam Jr. to do some research on Yan. His report included the following information:

“Yan’s three year stay here was so unusual that in his last year, the Chairman of the Faculty (the chief administrative officer of the University in those days) conferred Virginia status on him in the matter of payment of his fees, remarking, according to Yan, ‘You have been so long in our state that we can consider you a Virginian.’”

Yan died in 1950.

- With background reporting from Justin O’Jack, director of UVA's China Office.

Media Contact

Article Information

January 7, 2016

/content/mysterious-origin-chinas-possible-version-uvas-rotunda