“We had two clients, one with 10 family members and one with four,” Elliott said of the initial assignments. “In the course of a week, we turned over the first wave.”

The initial activity demonstrated that students could handle the challenge. The Charlottesville-Albemarle Bar Association’s pro bono coordinator, Kristin Clarens, launched the effort, in coordination with the Legal Aid Justice Center and the Law School’s Pro Bono Program.

The students have been working under the supervision of attorney Tanishka Cruz, who previously co-taught the Law School’s Immigration Law Clinic.

“Students are taking the lion’s share of the paperwork,” said Clarens, who praised Cruz for adding the supervision to her already busy workload.

“It’s really hard work when you think about they’re collecting information on someone who is fleeing in Afghanistan. Humanitarian parole is not usually used on a large scale like this. This is kind of an unprecedent demand, up 1,000% right now.”

She added that the process didn’t ramp up until late September because local organizers were worried that Afghans would go to Kabul’s airport and be hurt or killed if they showed their approvals. “We waited to see if humanitarian paroles would be effective,” she said.

One of the local families said they felt lucky that their loved ones didn’t go to the airport during the final airlifts, Elliott said.

“Thankfully, they held off on doing that,” he said, “because we quite possibly would have had a situation where the family members were waiting in the airport at the time of the bombing.”

While the students don’t speak directly to the endangered family members on the ground in Afghanistan – referred to as “beneficiaries” under the parole system – they do get regular updates through the families who are petitioning the U.S. government. Most of the petitioners speak English, making it easier to pass on information, but Charlottesville also has community translators who help, and the Legal Aid Justice Center can teleconference with a translations service.

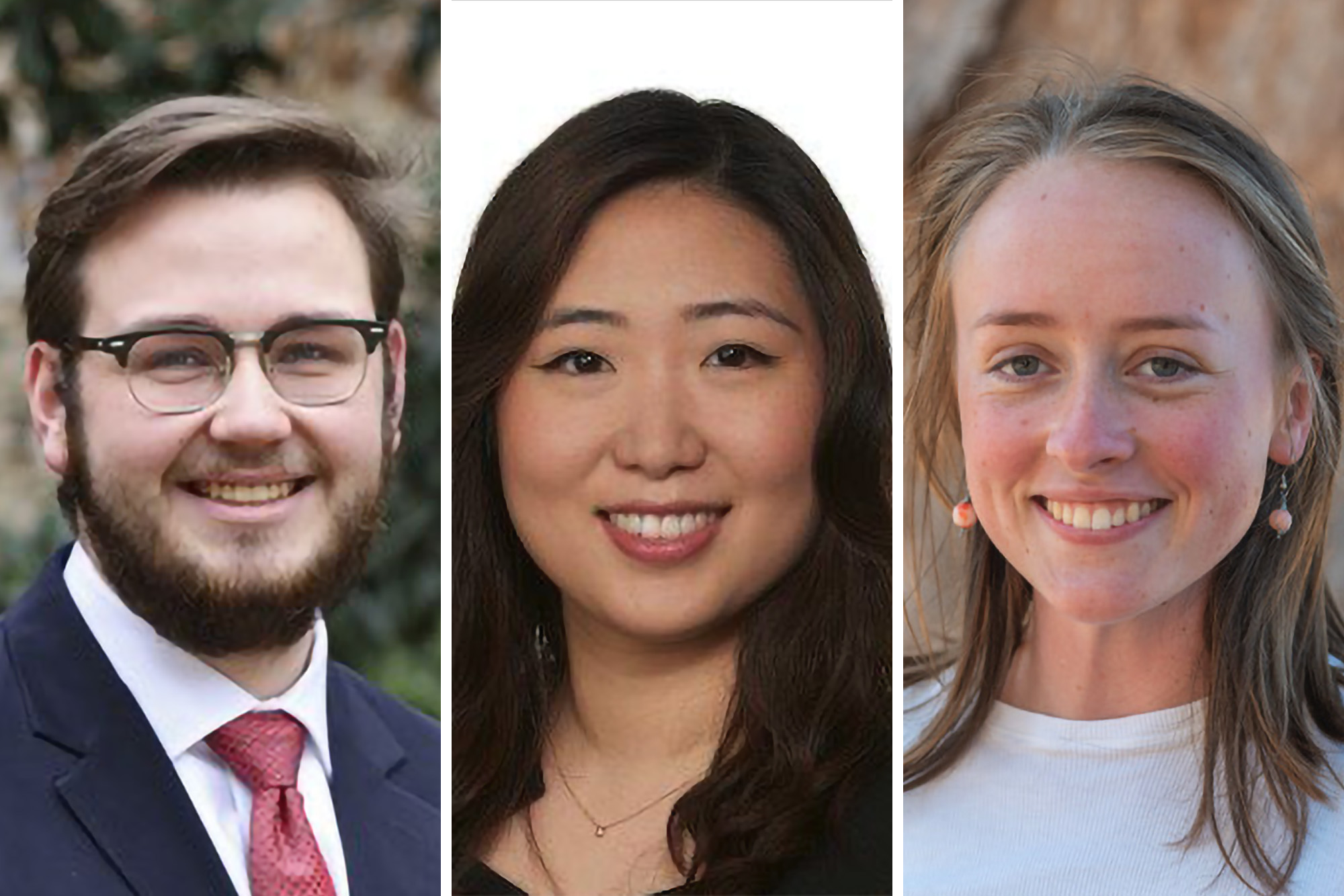

Jina Shin, another first-year law student, joined the second round of volunteerism, which has grown to 12 students handling about six application packets each.

“I had been following the news and when I saw the project listed as a pro bono project. I immediately thought, ‘That sounds like something where I can help people,’” Shin said. “I used to be a paralegal, so that helps me with putting together filings and putting exhibits together and stuff like that.”

Shin said the parole paperwork, despite its monotony at times, can be personally meaningful.

“I feel like maybe I can help in one small way,” she said. “I mean, obviously I personally can’t get a plane to get these family members out of Afghanistan, but I can help with one piece.”

Students and other volunteers hope to make a compelling case for the quickest action possible, adding details about any factors that might increase the risk of targeting. That could include not just being related to a special immigrant visa-holder, but also having been engaged in some form of teaching or activism under a freer society.

The process after an application has been filed can often be long and uncertain. But if a person can get out of the country, through private charter or across the mountains into Pakistan as two possibilities, students said, documents showing the U.S. will receive them are their tickets to being sent here.

Members of the International Refugee Assistance Project chapter at the Law School, led this year by second-year student Ariana Smith, have been participating in the ongoing effort. The UVA chapter is also helping asylees who are already here apply for permanent residency, an International Rescue Committee project.

“While we work with clients who are coming from a variety of different countries, this year there is, of course, an especially large need to assist Afghans,” Smith said. “Although humanitarian parole allows for lawful presence within the United States, it doesn’t confer any immigration status or provide parolees with a path to lawful permanent residence. Thus, once parolees arrive in the U.S., they must take additional steps before their parole expires to ensure that they can legally remain in the U.S. once the period of humanitarian parole has ended.”

The word “parole” is typically associated with release from prison. Clarens said that meaning isn’t far off from its immigration law use.

“‘Parole’ is connected closely to the idea of freedom,” Clarens said. “And it’s the best we can do right now to get them out of a dangerous situation and at a location where their request for longer-term residency can be heard.”

As of Oct. 18, the parole effort still had about 20 petitioners, with each having anywhere from one to 34 people they were trying to get to the U.S.

The number of requests is expected to continue to rise, Clarens said, and law students and immigration law attorney volunteers are still very much needed.

A separate, unrelated influx of about 250 new Afghan asylees to the Charlottesville area that was recently announced by the local news media shouldn’t affect the number of parole beneficiary requests. That is, she said, because that group isn’t arriving under special immigrant visa status.

Potential volunteers who wish to help with parole applications may contact Kimberly Emery, assistant dean for pro bono and public interest, at kemery@law.virginia.edu, or Clarens at kclarens@justice4all.org.

“This is the best way we can show up for the community here,” Clarens continued. “We want to do everything we can to preserve hope of escape for people in danger. We want to do everything we can, even if it’s a long shot.”