A new book penned by two University of Virginia law students details the history of the University’s Jefferson Literary and Debating Society, the oldest student organization on Grounds, of which Edgar Allan Poe and Woodrow Wilson were members.

“Society Ties: A History of the Jefferson Society and Student Life at the University of Virginia,” by Thomas L. Howard III and Owen W. Gallogly, chronicles the lively, invitation-only group, whose goals have changed over the society’s almost 200 years of existence, but whose primary mission has been to help members test and refine their ideas through debate and discussion.

The book is published by University of Virginia Press.

“From its inception, the Jefferson Society provided a forum for the free and often-heated exchange of ideas,” said Maurie D. McInnis, executive vice president and provost at the University of Texas at Austin, who co-founded the Jefferson’s University – Early Life Project while a professor of art history at UVA. “Students debated controversial topics, from slavery and foreign policy to the role of public education, from sectional tensions to integration and coeducation – an important window into the shifting dynamics of American life.”

Literary societies were once the social hub of American universities. For those aspiring to government service or other public roles, the societies filled a void by offering practice in writing, oratory and debate – as well as the chance to win the esteem of one’s peers. The societies also offered formal ceremonies that universities did not for many years, such as graduation exercises.

Owen W. Gallogly, left, and Thomas L. Howard III began their seven years of research as undergraduates. (Photos by Diego Valdez)

Authors Gallogly and Howard, friends since childhood, are now entering their second years at UVA’s School of Law. They began research for the book in 2010, while they were UVA undergraduates and fellow members of the society. At the time, the group’s archives of about 30,000 documents were not yet available for research purposes. A formal project to enshrine the archives, funded by the Jefferson Trust, began in 2015, and is ongoing.

“We pushed to be able to use the archives ourselves,” said Howard, who earned his bachelor’s in history and his master’s in higher education at UVA. “It was a subsequent generation of students who went through the Jefferson Trust and got a grant to restore the documents and do a lot of the digitization and cataloging. When we did the bulk of our work, it was in disarray.”

The documents date back more than 100 years. Most of the society’s older records perished in the Rotunda fire of 1895.

Gallogly, who earned his bachelor’s in political science and history, said sorting through the file cabinets on the second floor of Alderman Library, where the archives had been stored since the 1930s, presented a challenge: how to figure out where the most important information was.

“The society’s archives contained nearly 60 linear feet of largely unexplored materials,” Gallogly said. “There was no catalog or guide of any kind. We essentially had to start with the first drawer and work our way through, document by document.”

Despite the difficulty involved, the authors said the opportunity was one they couldn’t pass up.

“It was a chance to do substantive work in history,” Howard said. “We thought it would take about a year at the time; here we are, seven years later.”

Working from meeting notes, letters, publications and other materials, the pair filled in new details about the society, whose meetings gained a reputation over the years for being a boisterous battle of wits among UVA’s brightest thinkers. The meetings have occurred in Jefferson Hall (Hotel C on the West Range) since 1837. For many years, a beer keg at the corner of the room was the social lubricant that loosened tongues.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Gallogly and Howard found the society’s records ran the gamut of sobriety.

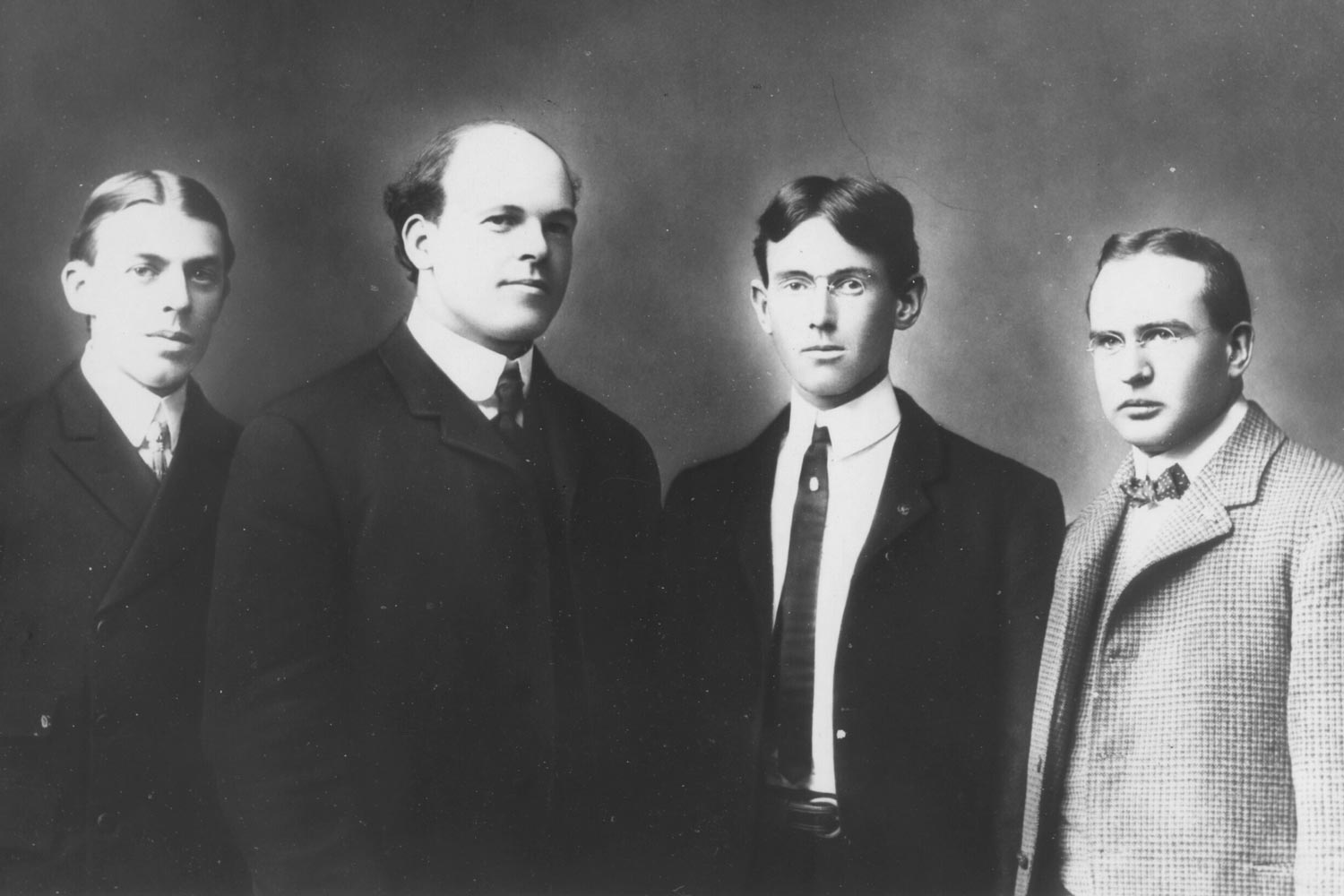

Woodrow Wilson, third from left, was photographed with fellow members of the society. In the fall of 1880 he became the society’s president.

On the more rigid side were the Wilson-era documents. The future president of the United States, who studied law at UVA from 1879 to 1880 and was also president of the society, had a penchant for institutional organization, evident in his contributions to the group’s constitution, still in place today, and in the governance structure he established for University of Virginia Magazine, which the society published.

On the flip side, minutes from the 1970s leaned toward the jokey and unenlightening, they said.

Among the unexpected artifacts they found were informal minutes from the society’s consideration in 1964 of Wesley Harris, who would become the group’s first African-American member. Harris would also become the first student, black or white, to complete UVA’s engineering honors program. He is currently a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he has served as an associate provost.

“Scrawled in the margin of a draft budget from the semester Harris was elected to the society is a set of sparse notes titled ‘Membership,’ which likely only survive because they were written on a financial document,” the authors write. “They lay out a strikingly candid assessment of points in favor and against both integration and Harris himself.”

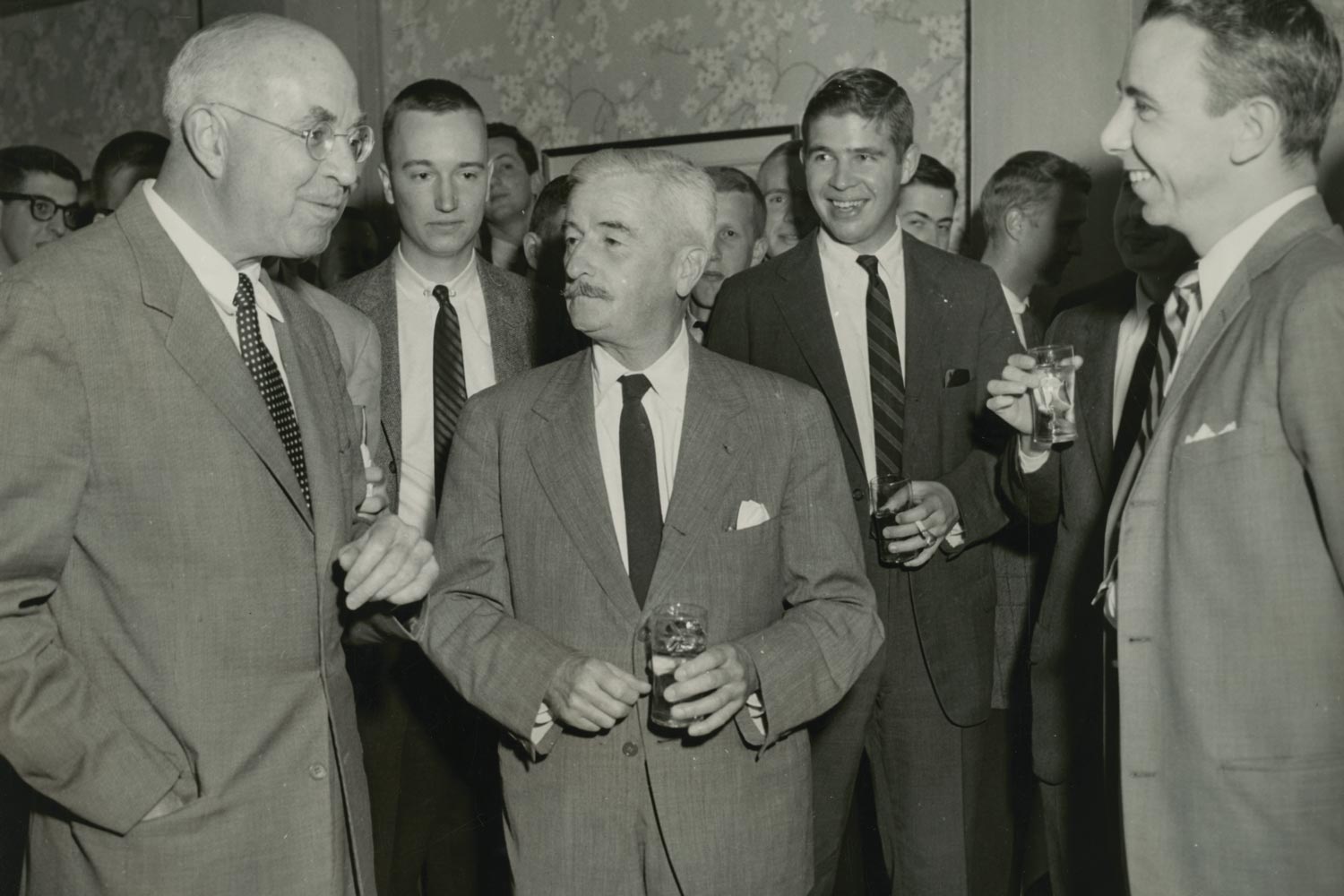

William Faulkner, center, and John Dos Passos, left, at a 1957 reception following an open Jefferson Society lecture delivered by Dos Passos. Faulkner was writer-in-residence at UVA from 1957-58.

The merits of the bright engineer from Richmond, who was skilled in debate from his high school days and who could converse on classical music, existentialism and other topics of intellectual heft, won them over.

Today, the society, which maintains a body of about 200 active members, is demographically and ideologically diverse, has women and men serving in top leadership roles and has no barriers to membership based on identity. Candidates still must interview to be considered, however.

“The society that I joined as a first-year in undergrad is very different than the society that exists now, and that will happen again and again and again,” Howard said. “That’s one of the reasons it’s almost 200 years old. Everyone can make of it what they want.”

Media Contact

Article Information

July 19, 2017

/content/law-students-uncover-stories-behind-uvas-oldest-student-society