About 40 local residents joined design consultants, University of Virginia representatives and students Friday night to consider ideas about what a memorial to the enslaved African-American workers who helped build and maintain the University might convey.

The idea of a memorial to UVA’s enslaved laborers has gained momentum and support over the past several years. It was built into the mission of the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University, which President Teresa A. Sullivan established three years ago.

The University’s Board of Visitors recently selected the Boston firm Höweler+Yoon to design the memorial, alongside three others who make up the design team: Frank Dukes, co-founder of University & Community Action for Racial Equity and past director of the Institute for Environmental Negotiation in the UVA School of Architecture; alumna Mabel O. Wilson, an architectural historian at Columbia University and an expert on race and the history of the built environment; and Gregg Bleam, a landscape architect who has taught at UVA and worked in and around the University for about 30 years.

Friday’s meeting, held at Mt. Zion First African Baptist Church in Charlottesville’s Ridge Street neighborhood, was a chance for the community to share some ideas behind a memorial design, especially about its purpose and meaning. They did not at this point discuss or suggest specific designs of what it might look like.

In convening the meeting, Dr. Marcus L. Martin, co-chair of the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University, said it was extremely important to have community input as the University goes through the design process.

The process will involve extensive outreach with community groups and UVA staff, students, alumni and faculty, with the goal of translating their ideas into a design that resonates with the community, he said. The team has already held several meetings with different groups in the UVA community. It will also hold another public meeting Jan. 23 at 6 p.m. at the Jefferson School African-American Heritage Center.

The design team members told attendees they want to let various stakeholders know early on what the design process entails and share some of the approaches that could be considered. In addition to the design team, a memorial steering committee, convened by the Office of the Architect, oversees the project scope, budget, schedule and schematic design.

The design team plans to report to the Board of Visitors in the spring, and the board will approve the final project.

“It is an honor, yet at the same time, a burden and a challenge to tell history in an appropriate way,” Meejin Yoon said, adding that her firm has not made any drawings yet. “We bring together many people because this [the memorial] is bigger than any one person.”

A memorial tells not only about the past, but also the present, and projects into the future, she said. “We, the designers, are really translators.”

How best to commemorate the contributions of enslaved workers involves many considerations. Should the memorial be a place of solitude, information or action? Where should it be located?

She also asked, “Who does UVA expect will visit the memorial?” The Academical Village, for example, attracts many visitors and schoolchildren of all ages.

Should it portray the painful reality of suffering, or transcendence, or both? A memorial could bring out individuals’ stories. Should it make a connection to the local community and possible descendants of the slaves who worked on Grounds?

At UVA, “History is hiding in plain sight and it’s important for these stories to be told,” said Wilson, who recently published a book, “Begin With the Past,” about the process of creating the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington. “Memorials are not just for a place. They mark people, history, events.”

Yoon’s firm designed the Collier Memorial on Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s campus in honor of an MIT police officer, Sean Collier, who was shot and killed by Dzhokhar Tsarnaev during the manhunt following the April 15, 2013, Boston Marathon bombing. That memorial – a granite, five-pointed structure – is large enough for people to walk around and provides space for contemplation.

Whether a memorial is abstract or representational is a major decision, she said, showing photos of several examples, including the Vietnam Memorial, which received criticism that it was too abstract, prompting a sculpture of several soldiers to be erected nearby.

Participants discussed several questions in small groups, then shared their thoughts and responses with the whole audience.

Some felt the memorial should be easily recognizable and visible in what it would stand for. If it was abstract, it would require too much explanation, one person said.

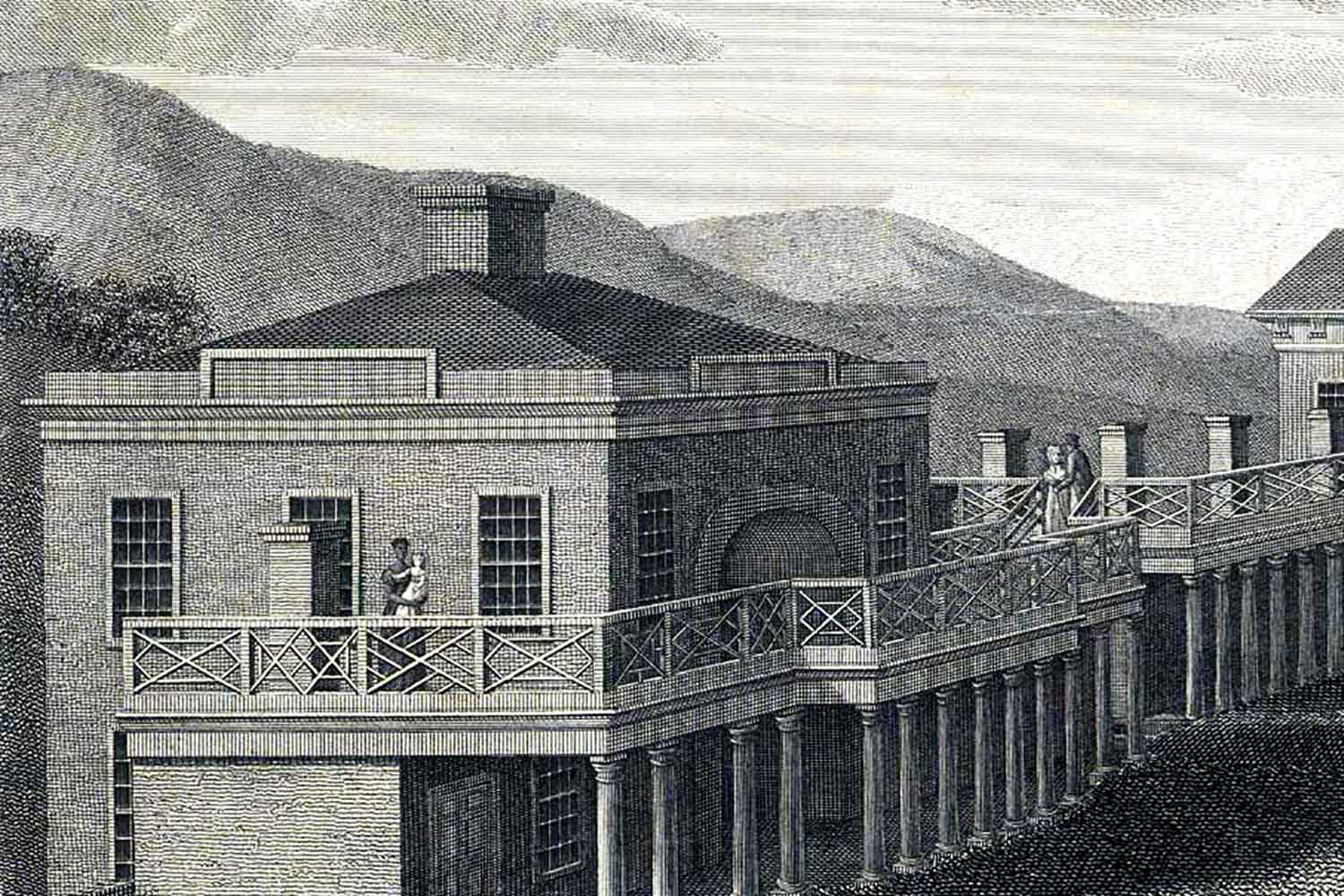

The location, as well as the scale, of UVA’s memorial also will be important factors, design team members said. A greensward area near Brooks Hall and a site alongside McCormick Road near Alderman Library where the Anatomical Theater once stood are two suggested locales that have emerged for their accessibility and visibility.

It might be advantageous for the memorial to be situated within the UNESCO World Heritage Site, the area of Central Grounds, said another participant. Other spots that would mark where enslaved African-Americans lived and worked also have been proposed, such as the garden behind Pavilion IX near McGuffey Cottage.

Another question the participants pondered was if and how the memorial could speak to the present, especially present racial conditions, and that seemed to give attendees pause. Perhaps that would be expecting too much from this memorial, someone suggested.

“It should shine a light on injustice,” one person said.

The participants agreed strongly on one point: that education be a key component. Generations of students could and should learn more about slavery history from the memorial, a few people commented. It could impart a sense of responsibility to confront the legacies and economic system of slavery that they’d carry into their daily lives and into the future.

Ways to Get Involved

• Attend the next public meeting on the memorial to enslaved laborers Jan. 23 at 6 p.m. at the Jefferson School African-American Heritage Center.

• See the website, which will be populated with information later this week.

• Take the survey to contribute ideas about the memorial here.

• Follow @uvamemorial on Instagram.

• Become a community ambassador to visit other local groups or send ideas to uvamemorial@gmail.com.

Media Contact

Article Information

December 5, 2016

/content/local-residents-mull-design-issues-uva-memorial-enslaved-laborers