July 12, 2007 -- It was with us every step of the way. Celebrating the anniversary of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta; eating dinner at Davis’ Café in Montgomery, Ala.; crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma; and sitting in the pews of the16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham.

The past was our constant companion, and we welcomed it with open arms. After all, immersing ourselves in the past was the reason we had signed on for the tour. As voyagers with the Civil Rights South Tour, we wanted to walk in the footsteps – sometimes quite literally – of the ordinary people who had effected extraordinary changes during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

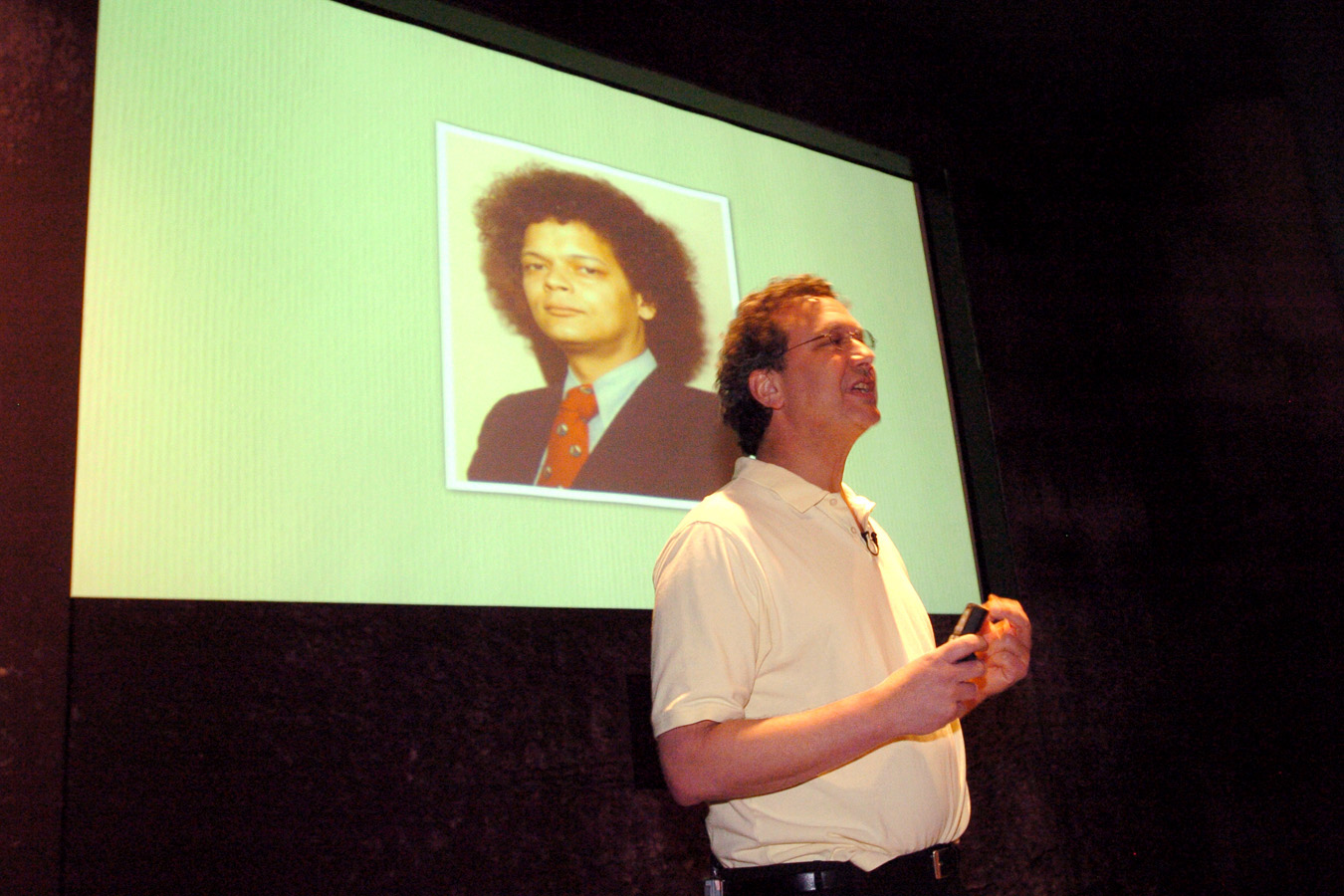

Sponsored by the Virginia Voyages program, the trip was a first for the University of Virginia: a tour of civil rights landmark sites led by history professor Julian Bond. By every measure, it was a success. Regardless of our respective ages or knowledge about the history of the American civil rights movement, we voyagers came away from the experience with a richer understanding of the events and people who helped to change race relations in America.

During the tour, reporting on the day’s events was my immediate focus. Each day, we visited sites and met with people associated with the civil rights struggle. Each evening, I wrote my dispatch for the next day. One of the places that we visited — the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery — received no mention in my dispatch of March 20, the day we visited the city. The omission was intentional.

I knew that once the trip was over, I wanted to devote a separate article to the SPLC and how it serves as a bridge between the past and present, between the goals first articulated during the civil rights movement and contemporary ideals of equality, justice and tolerance.

That was then. This is now.

Though many historians mark the end of the American civil rights movement as 1968, the year of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, racial inequality and discrimination have not disappeared. Since the tour concluded in late March, radio talk-show host Don Imus set off a firestorm of protest when he made racially and sexually derogatory comments about the Rutgers University women’s basketball team. Imus was subsequently fired for his remarks. Another example of how race continues to be a hot-button issue is the intensifying national political debate about immigration reform. On May 1 in Los Angeles, in a scene reminiscent of 1960s civil rights marches, police officers fired tear gas and rubber bullets on marchers at an immigration rights rally in MacArthur Park.

Founded in 1971, the SPLC began as a small civil rights law firm in Montgomery. In the years since, it has grown in size and scope and is now internationally known. It occupies a large building just up the hill from the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where King began his pastoral career.

It was a March morning the day we visited the SPLC’s Civil Rights Memorial Center, but already the temperature had climbed into the 80s. We gladly left the heat for the comfort of its 56-seat theater to listen to Morris Dees, the SPLC’s co-founder and chief trial counsel. He is the SPLCs most public face, receiving both warm praise and death threats for his efforts. When he and Joseph Levin formed the center as a nonprofit dedicated to seeking justice, they asked Bond to serve as its first president. Bond agreed and did so for years; today he serves on the center’s board of directors.

Dees began his presentation by talking about the symbolic import of the Civil Rights Memorial, located across the street from the center’s office building. Created by Maya Lin, who gained fame for her design of the controversial Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, D.C., the memorial is a circular slab of black granite etched with the names of 40 individuals who died between 1954 and 1968. Some were targeted for their active involvement in the civil rights movement. Others, like teenagers Emmett Till and John Earl Reese, were random victims of white “vigilantes determined to halt the movement.” Water burbles up from the center of the circle, flowing gently across the names and cascading down the sides. For the visitor, the effect is like looking in a mirror.

One of the SPLC’s earliest — and most effective — strategies for combating racial injustice was to represent victims of racial violence in civil suits against white supremacist organizations. Dees is most proud of Beulah Mae Donald v. United Klans, which centered on the 1981 abduction, beating and hanging of Michael Donald, a 19-year-old black teenager, by two members of the Ku Klux Klan. The SPLC represented Donald’s mother, who emerged victorious with a $7 million verdict. Unable to pay that amount, the Klan was thus forced to sign over the deed to its property to Mrs. Donald. From that moment on, it was an essentially bankrupt enterprise.

“With the money from the sale of the Klan’s property, Mrs. Donald purchased the first piece of land she had ever owned. The Donald case was not technically the first case filed against the Klan,” Dees noted. “But it was the most successful one.”

Our next speaker was Richard Cohen, the SPLC’s president and chief executive officer as well as a 1979 graduate of the University of Virginia’s School of Law. With images of civil rights marchers and their nemeses — including Alabama Governor George Wallace — fading in and out on a large screen behind him, Cohen made clear why an organization like the SPLC was so crucial in the years following the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and other civil rights legislation.

“The civil rights laws were not self-executing,” he said. “They needed determined advocates to see that they were followed.” In 1980, with the resurgence of white supremacist groups like the Klan, the SPLC figured as just such an advocate.

Like Dees, Cohen has had his share of courtroom battles on behalf of victims of racial injustice. Shortly after Cohen joined the SPLC in 1986, Dees asked him to handle a discrimination case against the Alabama Highway Patrol, which for years had refused to promote black troopers. A federal court sought to correct this injustice by requiring the state to promote one black trooper for every white trooper promoted until fair tests could be developed. The U.S. Justice Department under the Reagan administration was asking the court to reverse the order. Arguing before the U.S. Supreme Court, Cohen defended the federal order as an essential step toward integrating the upper ranks of the troopers. Against formidable odds, he won the case. The federal order stood.

Since then, Cohen has seen the full flowering of the SPLC’s effort to promote justice and equality. Today, it not only vigorously defends the ideals handed down from the civil rights movement but also sponsors programs whose aims include teaching tolerance to schoolchildren and advocating for juvenile justice. In 2004, the SPLC also launched the Immigrant Justice Project, which addresses the unique legal needs of migrant workers.

Near the end of his presentation, Cohen projected a U.S. map onto the screen. Part of the Intelligence Project, the map shows the SPLC’s effort to track hate group activity in all 50 states. As of 2006, Cohen noted, Virginia was home to 31 known hate groups. Then, he added, a man named Bill White, the self-styled commander of a neo-Nazi group called the American National Socialist Workers’ Party, lives in Roanoke and recently declared himself a candidate for mayor. That level of specificity undercut whatever general belief that any of us may have had about the ebbing of racial hatred. White supremacy groups aren’t relics from a bygone era. As the map made clear, they are alive and well.

Cohen ended his talk with a statement whose truth resonates as much today as it did throughout the civil rights movement 50 years ago: “We forget that we are not just history passing by, but that we are historical actors.”

The past was our constant companion, and we welcomed it with open arms. After all, immersing ourselves in the past was the reason we had signed on for the tour. As voyagers with the Civil Rights South Tour, we wanted to walk in the footsteps – sometimes quite literally – of the ordinary people who had effected extraordinary changes during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

Sponsored by the Virginia Voyages program, the trip was a first for the University of Virginia: a tour of civil rights landmark sites led by history professor Julian Bond. By every measure, it was a success. Regardless of our respective ages or knowledge about the history of the American civil rights movement, we voyagers came away from the experience with a richer understanding of the events and people who helped to change race relations in America.

During the tour, reporting on the day’s events was my immediate focus. Each day, we visited sites and met with people associated with the civil rights struggle. Each evening, I wrote my dispatch for the next day. One of the places that we visited — the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery — received no mention in my dispatch of March 20, the day we visited the city. The omission was intentional.

I knew that once the trip was over, I wanted to devote a separate article to the SPLC and how it serves as a bridge between the past and present, between the goals first articulated during the civil rights movement and contemporary ideals of equality, justice and tolerance.

That was then. This is now.

Though many historians mark the end of the American civil rights movement as 1968, the year of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, racial inequality and discrimination have not disappeared. Since the tour concluded in late March, radio talk-show host Don Imus set off a firestorm of protest when he made racially and sexually derogatory comments about the Rutgers University women’s basketball team. Imus was subsequently fired for his remarks. Another example of how race continues to be a hot-button issue is the intensifying national political debate about immigration reform. On May 1 in Los Angeles, in a scene reminiscent of 1960s civil rights marches, police officers fired tear gas and rubber bullets on marchers at an immigration rights rally in MacArthur Park.

| Daily Journals from Civil Rights South Tour |

| March 18, Atlanta, Ga. |

| March 19, Tuskegee, Ala. |

| March 20, Montgomery, Ala. |

| March 21, Selma, Ala. |

| March 22, Birmingham, Ala. |

It was a March morning the day we visited the SPLC’s Civil Rights Memorial Center, but already the temperature had climbed into the 80s. We gladly left the heat for the comfort of its 56-seat theater to listen to Morris Dees, the SPLC’s co-founder and chief trial counsel. He is the SPLCs most public face, receiving both warm praise and death threats for his efforts. When he and Joseph Levin formed the center as a nonprofit dedicated to seeking justice, they asked Bond to serve as its first president. Bond agreed and did so for years; today he serves on the center’s board of directors.

Dees began his presentation by talking about the symbolic import of the Civil Rights Memorial, located across the street from the center’s office building. Created by Maya Lin, who gained fame for her design of the controversial Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, D.C., the memorial is a circular slab of black granite etched with the names of 40 individuals who died between 1954 and 1968. Some were targeted for their active involvement in the civil rights movement. Others, like teenagers Emmett Till and John Earl Reese, were random victims of white “vigilantes determined to halt the movement.” Water burbles up from the center of the circle, flowing gently across the names and cascading down the sides. For the visitor, the effect is like looking in a mirror.

One of the SPLC’s earliest — and most effective — strategies for combating racial injustice was to represent victims of racial violence in civil suits against white supremacist organizations. Dees is most proud of Beulah Mae Donald v. United Klans, which centered on the 1981 abduction, beating and hanging of Michael Donald, a 19-year-old black teenager, by two members of the Ku Klux Klan. The SPLC represented Donald’s mother, who emerged victorious with a $7 million verdict. Unable to pay that amount, the Klan was thus forced to sign over the deed to its property to Mrs. Donald. From that moment on, it was an essentially bankrupt enterprise.

“With the money from the sale of the Klan’s property, Mrs. Donald purchased the first piece of land she had ever owned. The Donald case was not technically the first case filed against the Klan,” Dees noted. “But it was the most successful one.”

Our next speaker was Richard Cohen, the SPLC’s president and chief executive officer as well as a 1979 graduate of the University of Virginia’s School of Law. With images of civil rights marchers and their nemeses — including Alabama Governor George Wallace — fading in and out on a large screen behind him, Cohen made clear why an organization like the SPLC was so crucial in the years following the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and other civil rights legislation.

“The civil rights laws were not self-executing,” he said. “They needed determined advocates to see that they were followed.” In 1980, with the resurgence of white supremacist groups like the Klan, the SPLC figured as just such an advocate.

Like Dees, Cohen has had his share of courtroom battles on behalf of victims of racial injustice. Shortly after Cohen joined the SPLC in 1986, Dees asked him to handle a discrimination case against the Alabama Highway Patrol, which for years had refused to promote black troopers. A federal court sought to correct this injustice by requiring the state to promote one black trooper for every white trooper promoted until fair tests could be developed. The U.S. Justice Department under the Reagan administration was asking the court to reverse the order. Arguing before the U.S. Supreme Court, Cohen defended the federal order as an essential step toward integrating the upper ranks of the troopers. Against formidable odds, he won the case. The federal order stood.

Since then, Cohen has seen the full flowering of the SPLC’s effort to promote justice and equality. Today, it not only vigorously defends the ideals handed down from the civil rights movement but also sponsors programs whose aims include teaching tolerance to schoolchildren and advocating for juvenile justice. In 2004, the SPLC also launched the Immigrant Justice Project, which addresses the unique legal needs of migrant workers.

Near the end of his presentation, Cohen projected a U.S. map onto the screen. Part of the Intelligence Project, the map shows the SPLC’s effort to track hate group activity in all 50 states. As of 2006, Cohen noted, Virginia was home to 31 known hate groups. Then, he added, a man named Bill White, the self-styled commander of a neo-Nazi group called the American National Socialist Workers’ Party, lives in Roanoke and recently declared himself a candidate for mayor. That level of specificity undercut whatever general belief that any of us may have had about the ebbing of racial hatred. White supremacy groups aren’t relics from a bygone era. As the map made clear, they are alive and well.

Cohen ended his talk with a statement whose truth resonates as much today as it did throughout the civil rights movement 50 years ago: “We forget that we are not just history passing by, but that we are historical actors.”

Media Contact

Article Information

July 12, 2007

/content/looking-back-civil-rights-south-tour-three-months-later