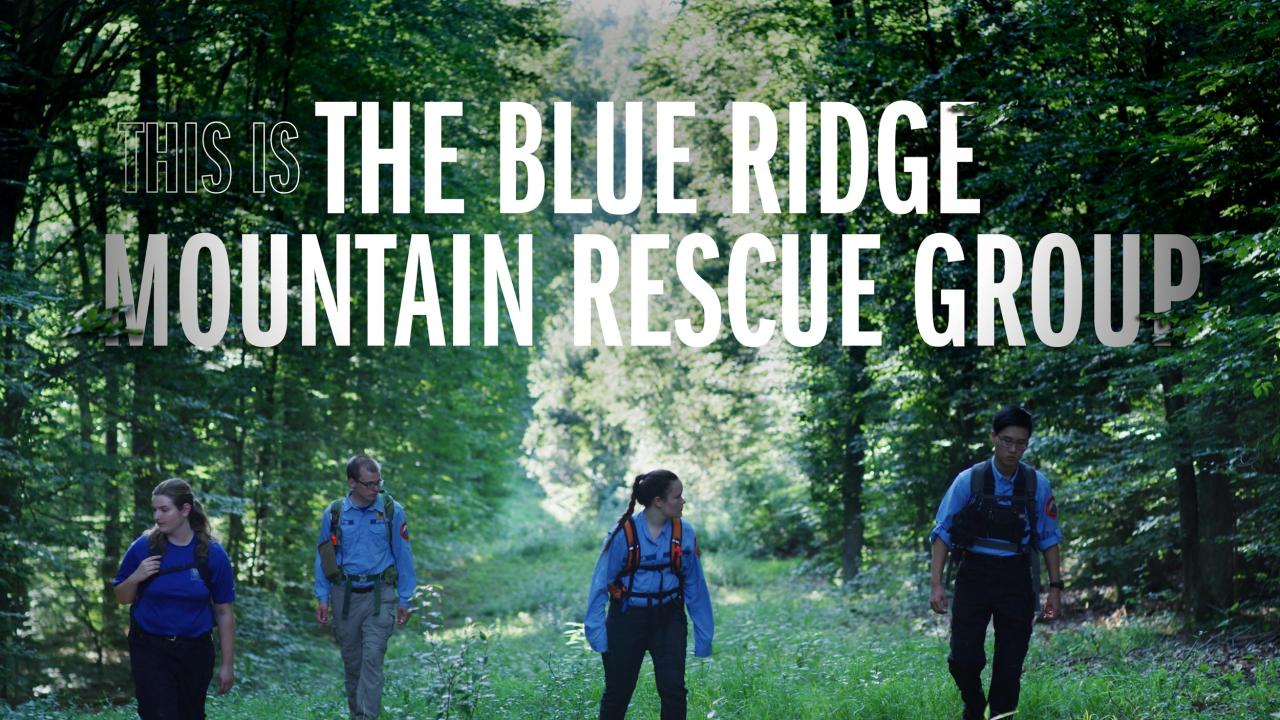

An avid outdoorsman who reached the rank of Eagle Scout, Koester joined a UVA club, the Blue Ridge Mountain Rescue Group, in 1981 as a first-year student. “The club is where I learned all my basic skills 40 years ago,” he said.

Koester never left Charlottesville and founded his company, dbS Productions, right after he graduated from UVA. As a graduate student, Koester made educational videos for the Department of Biology and his company initially expanded on that work. Today his firm’s tagline is “the source of search and rescue research, publications and training.” His groundbreaking work has been featured in NPR, Wired, Scientific American, Outside Magazine, Backpacker, New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, CBC, NBC and elsewhere.

Search and Rescue

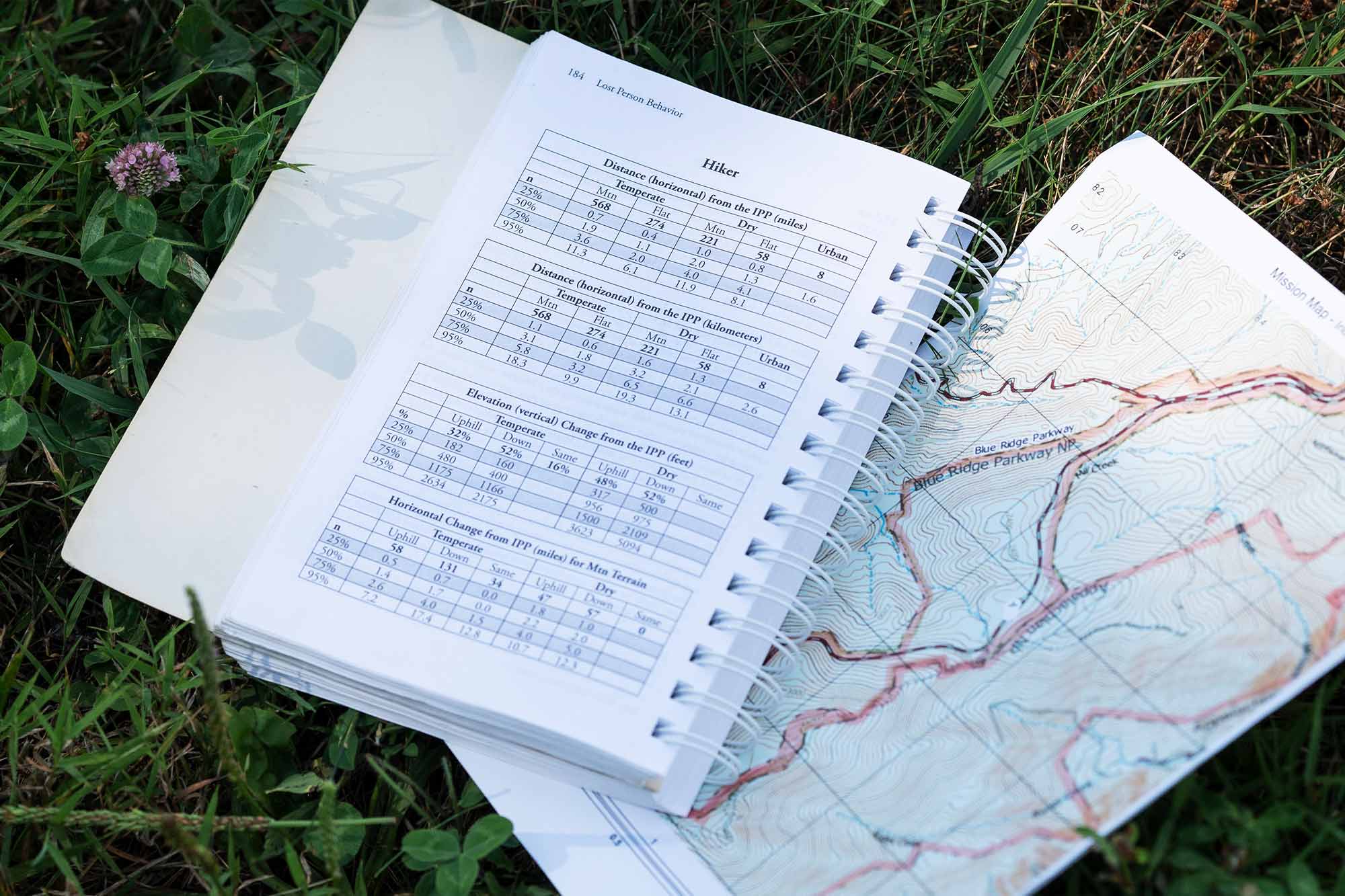

Koester has participated in hundreds of searches, serving as the incident commander in more than 100 of them. He created the International Search and Rescue Incident Database, which houses the analysis of more than 183,000 search-and-rescue incidents from around the world and is still growing.

His analysis of lost persons has led to Koester’s 96% search-and-rescue success rate, he said. From the database and his decades of experience, Koester has gleaned patterns that help rescue workers guide their searches for the lost. Essentially, he’s able to make predictions about what different kinds of lost people might do, similar to how a criminal profiler might predict where a bad guy will strike next.

The four most common categories of people who get lost are hikers, hunters, people with dementia and children.

Then there are subject categories, roughly broken up into five broad categories.

“The first is driven by external influences,” Koester said. “Examples of that would be somebody goes into the water; the water is going to drive where they are. If somebody is abducted, the perpetrator determines where they’re going to be found. If somebody is in an airplane falling out of the sky, the physics of how airplanes fall out of the sky determines where they’re going to be found.”

The next category is what Koester calls “wheels or motorized.” That would be lost cases that involve cars, motorcycles, all-terrain vehicles, mountain bikes or the like.

“Then the next class is altered cognitive conditions. So, this is where the dementia cases, the autism cases, intellectual disability, brain trauma, mental illness, despondent people or those with substance intoxication – all would go to that category,” Koester said.

Then comes children who have not fully developed their cognitive skills. They are broken up into three-year age groups, “starting at 1 to 3 and 4 to 6, and so on, up to the age of 15,” Koester said.

Finally, the question is what activity was the person doing? Hiking? Skiing? Something else?

Decision Points

So, what happens when a person gets lost? Taking the example of a hiker, Koester said people in the wilderness can get befuddled by what he calls “decision points.”

“This is where typically the trail got kind of confusing. Trail junctions, animal trails and sharp turns all traditionally get people kind of going the wrong way,” Koester said. Then they keep going. This is what is called “terrain analysis.”

“Then the brain usually sends a couple of subconscious warning signals. Anxiety is starting to go up. Things aren’t jiving between where they think they should be and what they’re actually seeing,” Koester said. Unfortunately, that is where people in a panic often convince themselves they are headed in the right direction.

Finally, the hiker realizes they are lost. Once that happens, Koester said “basic fight, flight or freeze mode” kicks in.